Unit 4: Coaching for Longevity¶

Chapter 4.27: Behavior Change for the Long Haul¶

[CHONK: Introduction]

One key truth separates longevity coaching from most other health work: You're not training someone for a 12-week transformation. You're helping them build a life.

Most clients who come to you have tried programs before. They've done the 30-day challenge, the 8-week boot camp, the quick-fix detox. And here they are again, which tells you something about how those approaches worked out.

The statistics are humbling. Research shows that roughly 30-35 percent of weight lost through intensive programs is regained within the first year.1 By year five, many intervention effects fade entirely. One five-year follow-up of a digital health behavior support system found no significant difference between intervention and control groups.2

If those numbers feel a bit discouraging, that's a completely normal reaction.

This isn't because people lack willpower. It's because short-term programs are designed for short-term results. They don't address the real question: How do you maintain healthy behaviors across decades, through job changes, family crises, health scares, and the general chaos of being human?

That's what this chapter is about.

[CHONK 1: The Decade View—Why Longevity Coaching is Different]¶

Thinking in years, not weeks¶

When someone hires a personal trainer for a wedding, the goal is clear: look good in photos on a specific date. The timeline is finite. The motivation is external. And frankly, sustainability doesn't matter, they just need to get there.

Longevity coaching is the opposite of this.

Your clients aren't preparing for an event. They're preparing for the next 20, 30, or 40 years of their lives. The people who succeed at long-term behavior maintenance aren't the ones who go hardest. They're the ones who keep going.

This requires a fundamental mindset shift, both for you and for your clients.

The adherence paradox¶

This might sound counterintuitive, but 80 percent adherence sustained over years beats 100 percent adherence that burns out in months.

We call this the "adherence paradox." The client who exercises five days a week consistently for three years gets better results than the one who trains seven days a week for six months and then completely stops.

Research supports this. Long-term maintainers—people in registries like the National Weight Control Registry who've kept weight off for a decade—don't follow perfect protocols.3 They have systems that work for their lives. They recover from setbacks. They adjust when circumstances change.

One meta-analysis found that habit-focused interventions increased physical activity habit strength compared to controls, with shorter follow-ups (12 weeks or less) showing larger effects than longer ones.4 This suggests that building the habit matters more than optimizing the specific behavior.

Identity versus outcomes¶

There's a meaningful difference between "I'm trying to lose weight" and "I'm a person who takes care of my health."

The first is an outcome goal. It's external, measurable, and, critically, it has an endpoint. Once you lose the weight, what then? The motivation evaporates.

The second is an identity statement. It describes who you are, not what you're trying to achieve. And because identity is ongoing, so is the behavior that supports it.

Research on "future self-continuity", the degree to which people feel connected to their future selves, shows this matters for behavior.5 People who can vividly imagine their future selves make more health-protective choices in the present. They save more money, exercise more, and engage in fewer risky behaviors.

What success looks like over 10+ years¶

Long-term success looks different than short-term success. Here's what the research shows about people who maintain healthy behaviors for years:

They're not perfect. The National Weight Control Registry found that over 87 percent of members maintained at least 10 percent weight loss at both 5 and 10 years, but this was a self-selected group of highly motivated people, and even they had ups and downs.3

They stay engaged. One analysis of a low-cost weight management program (TOPS) found that members who renewed annually maintained an average weight change of -6 percent at one year and -8.3 percent at seven years.6 Continued participation predicted continued success.

They adapt. Long-term maintainers use proactive planning and continued self-monitoring, while regainers tend to relax monitoring and planning over time.7

They have support. Social context is pivotal: peers and family who support healthy behaviors facilitate long-term maintenance, while unsupportive social environments predict relapse.8

Predictors of long-term success¶

The research identifies several factors that predict better long-term adherence:

- Older age (yes, really, older adults often have more stable routines)

- Higher education and socioeconomic status (access to resources matters)

- Larger initial success (early wins build momentum)

- Higher readiness to change at baseline

- Lower depression and stress (mental health affects everything)

- Intrinsic motivation (doing it for yourself, not external validation)9,10

Notably, motivation type matters. One study found that participants motivated by stress reduction had nearly three times higher odds of progressing toward lifestyle goals, while those primarily motivated by weight loss had lower odds of success.11 This suggests that framing behavior change around how you want to feel, rather than how you want to look, may support longer-term maintenance.

Coaching in Practice: The 10-Year Client¶

[CHONK: Coaching in Practice - The 10-Year Client]

Marcus, 52, comes to you after losing 40 pounds on a popular program, and regaining 35 of them over the following two years. He's frustrated and feels like a failure.

What NOT to do:

❌ Immediately plug him into another strict short-term plan without exploring what he really wants for the next decade.

Why it doesn't work: He stays stuck in the same lose-regain cycle and reinforces the story that he's a failure when the plan ends.

What TO do:

✅ Shift the focus to who he wants to be and what he wants to be able to do 10 years from now.

Instead of immediately diving into a new plan, try this conversation:

Coach: "Marcus, let me ask you something different. Forget weight for a moment. When you imagine yourself at 62—10 years from now—what do you want to be able to do?"

Marcus: "I want to be able to hike with my grandkids. Keep up with them, you know?"

Coach: "That's a great picture. Now my question is this: What would 62-year-old Marcus thank you for starting today? Not a crash diet, but something sustainable enough that you'd still be doing it in 10 years?"

Key takeaway: This reframes the conversation from short-term weight loss to long-term capability: an identity-based, decade-view approach. |

[CHONK 2: Habit Formation for Lasting Change]¶

The myth of 21 days¶

You've probably heard that it takes 21 days to form a habit. This number gets repeated constantly, and it's wrong.

The actual research tells a different story. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 20 studies found the median time to habit formation was approximately 59-66 days, with a mean of 106-154 days and observed range of 4-335 days.12

Let that sink in. Some behaviors become automatic in under a week; others take nearly a year. And the median—the midpoint—is about two months, not three weeks.

If you're realizing why some of your own past habit attempts felt harder than you expected, that's normal.

This matters for your clients. If they expect habits to feel automatic in 21 days and they don't, they may conclude something is wrong with them. Knowing the real timeline helps set appropriate expectations.

The cue-routine-reward loop¶

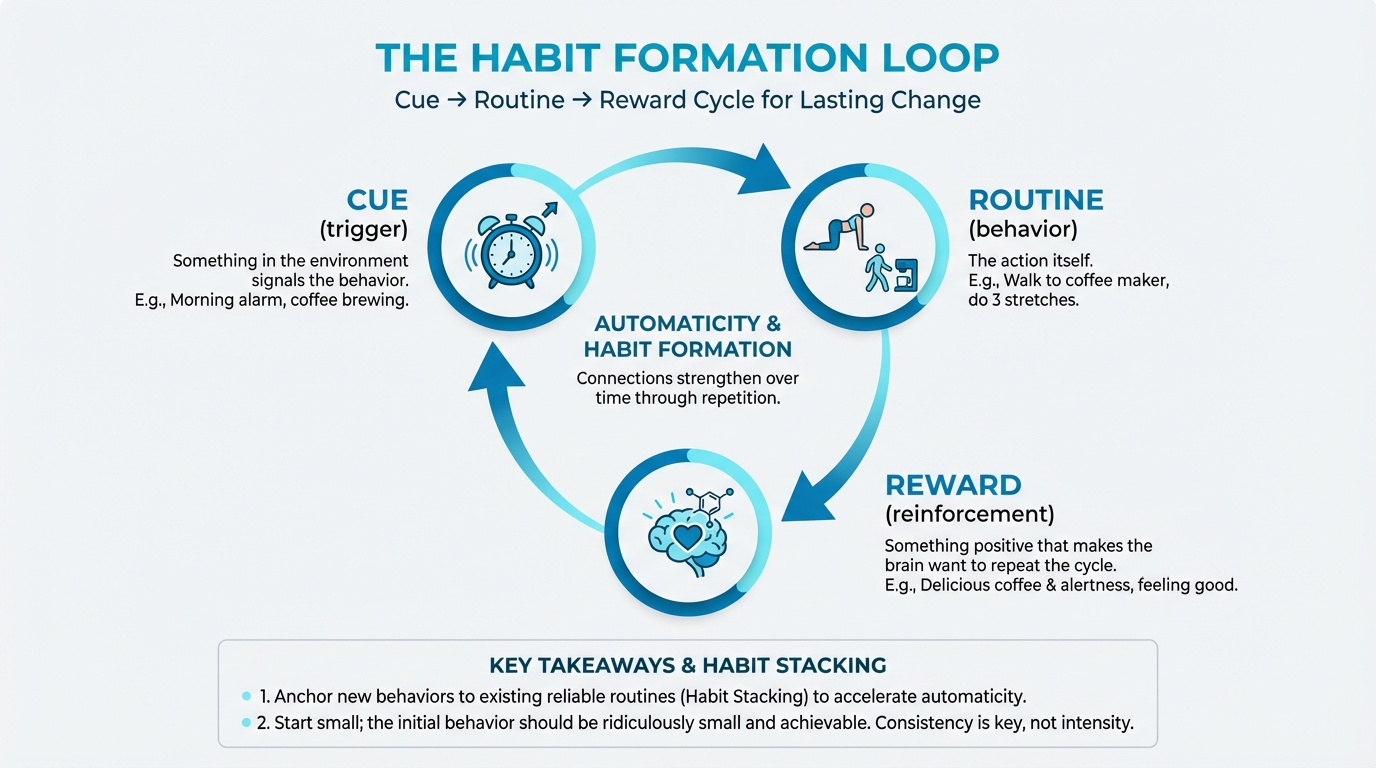

Habits work through a predictable cycle:

- Cue (trigger): Something in the environment signals the behavior

- Routine (behavior): The action itself

- Reward (reinforcement): Something positive that makes the brain want to repeat the cycle

Figure: Cue → Routine → Reward cycle

For example: Morning alarm goes off (cue) → walk to coffee maker (routine) → delicious coffee and alertness (reward).

The key insight is that the cue matters enormously. Research shows that repeating behaviors in stable contexts—same time, same place, same preceding event—predicts higher automaticity and greater goal attainment.13

This is why people who exercise "when they feel like it" rarely develop an exercise habit, while people who exercise "immediately after dropping the kids at school" often do. The stable cue creates automaticity.

Context stability and anchoring¶

"Anchoring" means connecting a new behavior to an existing routine that already happens consistently. Research found that anchoring meditation to a fixed daily routine increased odds of daily practice by about 14 percent compared to controls.14

Practical examples of anchoring:

- Take vitamins right after brushing teeth (existing routine: tooth brushing)

- Do mobility exercises while waiting for coffee to brew (existing routine: morning coffee)

- Practice deep breathing during the drive home from work (existing routine: commute)

The existing routine serves as a reliable cue. You don't have to remember to do the new behavior. It's attached to something you already do automatically.

Habit stacking for longevity clients¶

"Habit stacking" is anchoring multiple behaviors together in a chain. The formula is: After [CURRENT HABIT], I will [NEW HABIT].

For longevity clients, this might look like:

- After I pour my morning coffee, I will take my omega-3s

- After I sit down at my desk, I will do five wall push-ups

- After I brush my teeth at night, I will do five minutes of stretching

- After I park at work, I will take a 5-minute walk before going inside

The key is specificity. "I'll exercise more" is not a habit stack. "After I drop my keys by the door when I get home, I will immediately change into workout clothes" is.

Identity-based behavior change¶

Charles Duhigg and James Clear have popularized the concept of identity-based habits, the idea that lasting change comes from changing who you believe you are, not just what you do.

The progression looks like this:

- Outcome-based: "I want to lose weight"

- Process-based: "I want to exercise three times per week"

- Identity-based: "I am a person who moves my body regularly"

Each successful behavior becomes a "vote" for the identity. Over time, the identity strengthens, and the behaviors feel less like effort and more like self-expression.

This connects to the habit research. One study found that morning routines and self-selected behaviors were associated with stronger habit gains.12 When people choose behaviors that align with who they want to be, automaticity develops faster.

Keystone habits for longevity¶

Some habits seem to create positive ripple effects across other areas of life. Researchers call these "keystone habits."

For longevity clients, common keystone habits include:

- Morning movement: People who exercise in the morning tend to make better food choices throughout the day

- Adequate sleep: Sleep affects mood, willpower, food cravings, and exercise capacity

- Meal preparation: Having healthy food available reduces reliance on willpower in the moment

- Regular check-ins: Self-monitoring (without obsession) helps maintain awareness

The strategy: Instead of trying to change everything at once, help clients identify one keystone habit that might create positive spillover effects.

Early engagement predicts success¶

Here's an important finding from the research: Early engagement is one of the strongest predictors of long-term success.15

What happens in the first few weeks of a behavior change program often predicts what happens months or years later. Clients who engage strongly early, attending sessions, completing activities, building initial momentum, are more likely to maintain changes long-term.

This doesn't mean pushing clients to do more than they can sustain. It means creating conditions for meaningful early success. Start with behaviors that are achievable, visible, and reinforcing. Build confidence before building complexity.

Coaching in Practice: Building the Morning Anchor¶

[CHONK: Coaching in Practice - Building the Morning Anchor]

Priya, 47, wants to establish a consistent stretching routine to address her chronic back stiffness. She's tried starting programs many times but always abandons them.

Instead of prescribing a specific stretching routine, help her build a habit stack:

Coach: "What's something you do every single morning without fail, even on your worst days?"

Priya: "Make coffee. I literally can't function without it."

Coach: "Perfect. Here's what I want you to try: After you press the button on your coffee maker, you do just three stretches: cat-cow, child's pose, and a standing hamstring stretch. Takes maybe two minutes. The coffee brewing is your cue."

Priya: "That's it? Just three?"

Coach: "That's it. We're not building a stretching routine yet. We're building a habit. Once this feels automatic, we can add to it. But right now, the goal is just to connect stretching to coffee. Every single day."

Key takeaway: The initial behavior is almost ridiculously small. That's intentional. Two minutes is achievable even on terrible days. Once the cue-behavior connection strengthens, you can gradually increase the routine. |

[CHONK 3: Managing Health Anxiety and Optimization Obsession]¶

When "healthy" becomes unhealthy¶

There's an uncomfortable truth about the longevity and wellness space: Some of your most motivated clients may also be your most at-risk for developing problematic relationships with health.

The same traits that drive people to optimize their health—conscientiousness, goal orientation, desire for control—can tip into anxiety, obsession, and rigidity that actually undermines well-being.

Orthosomnia: Obsessing over sleep data¶

"Orthosomnia" is a term coined by sleep researchers to describe an obsessive pursuit of optimal sleep driven by tracker metrics.16 People with orthosomnia become so focused on achieving perfect sleep scores that they actually develop insomnia-like symptoms: difficulty falling asleep, anxiety about sleep, and daytime fatigue caused by worry rather than actual sleep deprivation.

One study found that orthosomnia prevalence ranged from 3 percent (strict criteria) to 14 percent (lenient criteria) among people who use sleep trackers.17 That's not a trivial number. And people with orthosomnia had significantly higher insomnia severity scores than other tracker users.

The irony is painful: People trying so hard to sleep well end up sleeping worse because of their efforts.

The broader pattern: Wellness perfectionism¶

Orthosomnia is part of a larger pattern. Research consistently links maladaptive perfectionism, a rigid need to meet impossibly high standards, to higher anxiety, depression, and problematic health behaviors like orthorexia (obsessive "clean eating") and compulsive exercise.18,19

A meta-analysis found significant correlations between perfectionism and compulsive exercise, with total perfectionism showing a correlation of approximately 0.37.20 Perfectionistic concerns—the fear of making mistakes and worry about others' judgment—showed correlations with both binge eating and compulsive exercise.

This doesn't mean all optimization is bad. Many clients benefit from tracking, planning, and striving for improvement. But there's a line between healthy engagement and unhealthy obsession. Some clients cross it.

Signs of problematic versus healthy tracking¶

Healthy tracking relationship:

- Uses data to notice trends and inform decisions

- Can take breaks from tracking without significant anxiety

- Data serves goals, not the other way around

- Can accept "good enough" results

- Tracking improves quality of life overall

Problematic tracking relationship:

- Feels anxious when unable to track or when data is missing

- Constantly checks metrics throughout the day

- Mood depends heavily on daily numbers

- Pursues perfect scores at the cost of actual well-being

- Cannot enjoy activities if not tracked

- Tracking creates more stress than it relieves

Research shows that most wearable users report more positive than negative emotions from tracking.21 But among users with pre-existing anxiety or perfectionism, the relationship can become counterproductive.

The "never enough" trap¶

Wellness culture can fuel a sense that you're never doing enough. There's always another supplement to take, another protocol to follow, another biohack to try. For some clients, this creates chronic low-grade anxiety that they're falling short.

If you or your clients have ever felt that constant pressure, that's understandable—much of wellness culture is built on the idea that you're never doing enough.

One study found that wearable use actually strengthened the link between short sleep and anxiety, meaning that for some people, knowing their sleep was poor made them feel even worse than just being tired would have.22

This is where the PN philosophy of "fundamentals first" becomes therapeutic, not just practical. When you help clients see that sleep, movement, nutrition, and connection provide the vast majority of health benefits, you're giving them permission to stop chasing marginal gains that increase their stress.

Sample coaching conversation¶

Coaching in Practice: Coaching the Anxious Optimizer¶

[CHONK: Coaching in Practice - Coaching the Anxious Optimizer]

Derek, 38, is a tech executive who tracks everything: sleep, HRV, glucose, steps, calories, macros. He came to you for help optimizing his longevity stack, but you've noticed some concerning patterns: he's anxious when his sleep score is below 85, he's stressed about fitting in his fourth sauna session this week, and he mentioned canceling dinner with friends because it would "mess up his fasting window."

What NOT to do:

❌ Applaud his dedication and add even more tracking, rules, or complex protocols.

Why it doesn't work: It reinforces the over-optimization that's already increasing his stress and social isolation.

What TO do:

✅ Get curious about how all this is affecting his quality of life and gently connect the dots between his behaviors and his well-being.

A conversation might sound like this:

Coach: "Derek, I want to ask you something, and I want you to answer honestly. All this tracking and optimizing, is it making your life better, or is it making you more stressed?"

Derek: "I mean... it's supposed to be making me healthier."

Coach: "That's not what I asked. How do you feel? Are you enjoying life more or less than before you started all this?"

Long pause.

Derek: "Honestly? I think about it constantly. I feel guilty when I miss something. I turned down a trip with my college friends because I didn't know if I could control my diet and sleep schedule."

Coach: "I want you to consider this: Chronic stress and social isolation are two of the biggest risk factors for early mortality. If your 'longevity protocol' is causing you to feel stressed all the time and skip time with friends, it might be working against your actual health goals. What if we simplify things significantly and see how you feel?"

Key takeaway: This conversation opens the door to scaling back. It doesn't pathologize Derek's interest in health. It redirects it toward what actually matters. |

Scope of practice: When to refer¶

This is critical: As a health and fitness coach, you are not qualified to diagnose or treat anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive patterns, or eating disorders. These require licensed mental health professionals.

Signs that warrant referral to a mental health professional:

- Tracking or health behaviors significantly interfering with work, relationships, or daily function

- Symptoms of anxiety that persist and cause significant distress

- Rigid food rules that cause nutritional deficiency or social isolation

- Compulsive exercise that continues despite injury or exhaustion

- Client expresses feeling unable to stop behaviors even when they want to

- Any indication of disordered eating patterns

- Signs of depression alongside health obsession

- Client's distress seems disproportionate to the situation

How to refer:

- Normalize seeking support: "Many high-achieving people work with therapists. It's like having a coach for your mental game."

- Be direct but caring: "What you're describing sounds like it's causing real distress. I think a therapist who specializes in anxiety could really help."

- Stay in your lane: "I can help you with the fitness and nutrition piece, but this other part is outside my expertise. Let's get you connected with someone who specializes in this."

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for health anxiety has strong evidence, with one study showing large effect sizes (d = 1.61) and 60 percent achieving reliable improvement.23 Your job is to recognize when a client needs this level of support and facilitate the connection.

[CHONK 4: Handling Setbacks, Plateaus, and Life Transitions]¶

Change isn't a straight line¶

If there's one thing you need to help clients understand, it's this: Behavior change is not linear.

The Sleep, Stress Management, and Recovery course describes how change actually works. Not as a smooth upward trajectory, but as "thirteen steps" that include setbacks, plateaus, and reversals.24 You start in what feels like a good rhythm, then something disrupts it. You recover, make progress, hit another obstacle. Two steps forward, one step back, sometimes two steps back.

This is normal. In fact, it's universal. Research on smoking cessation, one of the most studied behavior changes, shows that approximately 60 percent of people relapse within three months, and only 20-30 percent remain abstinent at one year.25 Yet many of those who eventually quit do so after multiple attempts.

The question isn't whether setbacks will happen. It's how you and your clients will respond when they do.

Distinguishing lapse from relapse¶

A lapse is a temporary slip: a missed workout, an off-plan meal, a week where everything falls apart.

A relapse is a return to old patterns: abandoning the new behaviors entirely.

The difference between people who maintain long-term change and those who don't isn't the absence of lapses. It's how they respond to them.

Research found that weeks with weight gain predicted continued gain the following week about 60 percent of the time.26 But the roughly 5 percent of weeks that showed recovery from a gaining trend were associated with increased physical activity during the gain week and more self-monitoring and goal engagement in the following week.

In other words: What you do during and immediately after a lapse determines whether it becomes a relapse.

The "expected unexpecteds"¶

Life will throw curveballs. The goal isn't to prevent disruption. It's to build resilience into the system so disruption doesn't derail everything.

Common life transitions that disrupt health behaviors include:

- Job changes: New schedules, new stress, new environments

- Relationship changes: Marriage and parenthood are both associated with decreases in physical activity27

- Health events: Illness or injury can force behavior changes

- Caregiving responsibilities: Taking care of aging parents or sick family members

- Moves: Relocation disrupts all routines (though it also creates a window for new ones, research suggests a roughly 3-month window where interventions are especially effective for recent movers28)

These aren't surprises. They're predictable parts of human life. Help clients anticipate them: "What's your plan for maintaining your exercise habit if you get promoted and your schedule changes?"

Rebuilding versus starting over¶

When clients return after a setback, resist the urge to start from scratch. They're not beginners, they've done this before. They have knowledge and skills. What they need is to rebuild, not restart.

Key differences:

Starting over (avoid this):

- Treats past experience as irrelevant

- Resets expectations to zero

- Ignores what worked before

- Creates a "fresh start" narrative that makes the next setback feel like another failure

Rebuilding (do this instead):

- Acknowledges what the client already knows

- Identifies what worked in the past and what didn't

- Starts from a platform of existing capability

- Creates a "recovery" narrative that normalizes the pattern

Retirement: A window of opportunity¶

One life transition deserves special mention: retirement. Unlike most transitions that disrupt healthy behaviors, retirement often creates opportunities for positive change.

Research found that retirees were 36 percent more likely to engage in sports activities than those still working.29 Another study showed retirement was associated with reduced smoking and alcohol use and increased exercise motivation (though also increased sedentary time).30

The key insight: behavioral adjustments around retirement began pre-retirement and took approximately 2-3 years to consolidate. For clients approaching retirement, this is an ideal time to establish new routines that will carry through the transition.

The coach's role: Compassion first¶

When clients come back after falling off track, their first need is not a new plan. It's emotional support.

Many clients feel shame about setbacks. They've "failed" in their minds. They expect disappointment or judgment. What they often get from well-meaning coaches is problem-solving mode: "Okay, let's figure out what went wrong and fix it."

That's the second step, not the first.

The first step is validation: "This is hard. Setbacks happen to everyone. You're here, which means you haven't given up. That matters more than the slip."

Research on relapse conceptualizes setbacks as learning opportunities: chances to understand triggers and build better systems.25 But clients can only access that learning mode once they've moved past the shame.

Coaching in Practice: The Post-Surgery Rebuild¶

[CHONK: Coaching in Practice - The Post-Surgery Rebuild]

Janet, 59, was making great progress before her knee replacement surgery. Now, three months post-surgery, she's back in your office. She's gained 15 pounds, lost most of her conditioning, and feels defeated.

Janet: "I basically have to start all over again. This is so frustrating."

Coach: "I hear the frustration. And I want to challenge one word you just used: 'over.' Janet, you're not starting over. You know how to meal prep. You know what exercises you respond to. You know your triggers and your strategies. That's not gone. It's just... offline temporarily."

Janet: "It doesn't feel that way. I feel like all my progress was wasted."

Coach: "The physical conditioning, yes, some of that will need to be rebuilt. But the knowledge? The habits that worked? The understanding of yourself? That's still there. We're not building from zero. We're rebuilding on a foundation. And frankly, you're going to progress faster this time because of everything you learned the first time."

Janet: "You really think so?"

Coach: "I know so. This is actually well-documented. People who've done something before relearn it faster. The neural pathways are still there. We just need to wake them up."

Key takeaway: The coach validates the frustration without agreeing with the "starting over" narrative. The reframe matters. It affects how Janet will approach the coming weeks. |

[CHONK 5: Progressive Autonomy—The Goal is Independence]¶

Your job is to work yourself out of a job¶

There's a paradox of good coaching: Success means the client eventually doesn't need you.

This isn't about losing business, it's about what actually serves the client. A dependent relationship where they can only maintain behaviors with your constant support isn't success. Independence, with optional check-ins, is.

Building self-coaching skills from day one¶

The best coaches don't just prescribe behaviors. They teach clients how to think about behavior. From the first session, you're building capacity for self-regulation.

This includes:

- Self-monitoring skills: Helping clients notice patterns in their own behavior

- Problem-solving frameworks: Teaching clients to troubleshoot obstacles

- Planning abilities: Showing clients how to anticipate challenges and create solutions

- Self-compassion practices: Helping clients respond to setbacks constructively

One study found that reductions in negative attitudes, increases in self-efficacy, and development of relapse-management skills all mediated long-term exercise adherence in heart failure patients.31 In other words, the skills mattered as much as the behaviors.

The GSPA model (brief reference)¶

Precision Nutrition's Change Psychology specialization introduces the GSPA model (Goals, Skills, Practices, Actions), a model for systematic behavior change. While a full explanation is beyond our scope here, the key insight is relevant: sustainable change requires building foundational skills, not just prescribing actions.

If you're interested in deepening your behavior change coaching abilities, the Change Psychology certification explores these models in detail.

Reducing frequency while maintaining progress¶

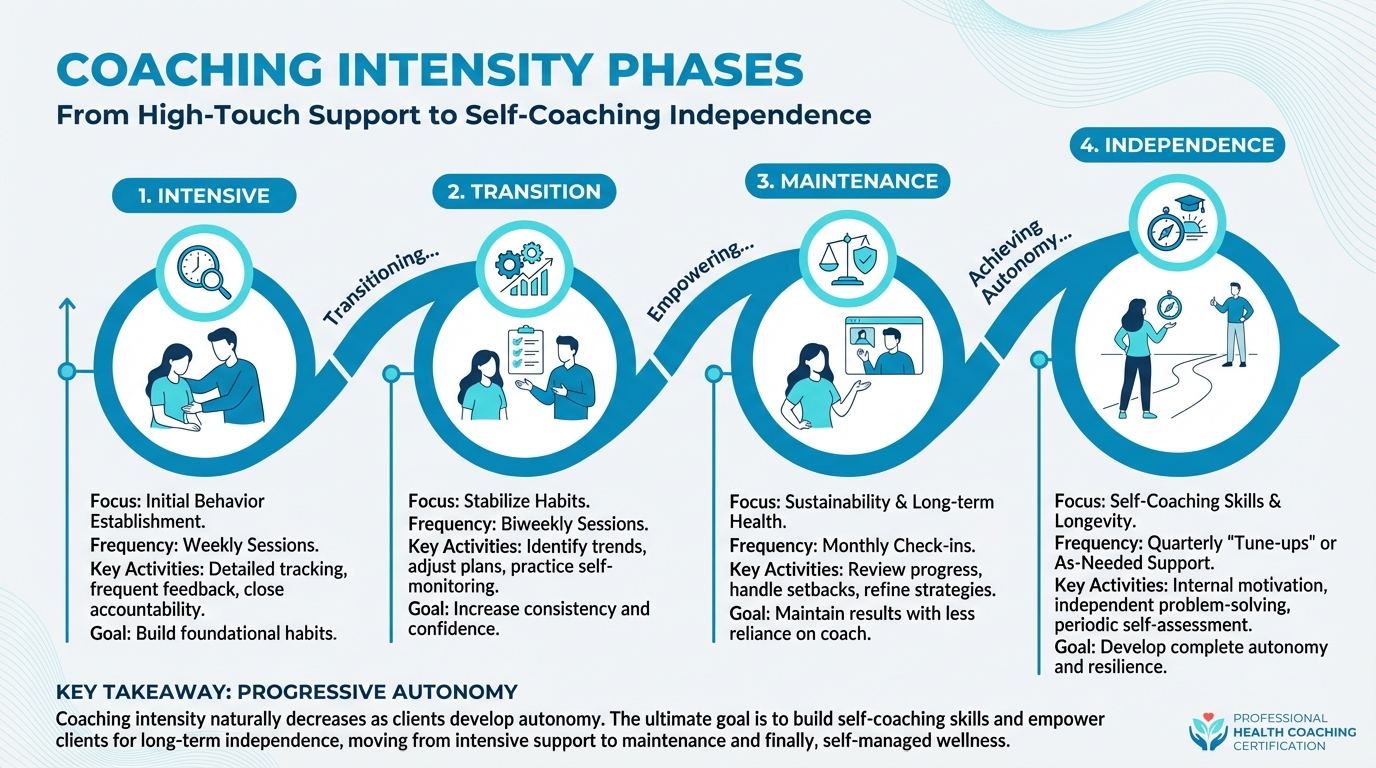

As clients develop autonomy, coaching intensity should naturally decrease. A typical progression might look like:

- Intensive phase: Weekly sessions during initial behavior establishment

- Transition phase: Biweekly sessions as habits stabilize

- Maintenance phase: Monthly check-ins

- Independence phase: Quarterly "tune-ups" or as-needed support

Figure: Intensive → Transition → Maintenance → Independence

Research suggests that ongoing contact supports maintenance, but the nature of that contact can evolve.32 Clients who've developed strong self-regulation skills may need only occasional accountability, while those with complex situations may benefit from longer-term support.

Signs a client is ready for independence¶

- They can identify their own obstacles before they become problems

- They recover from setbacks without major intervention

- They adapt their behaviors when circumstances change

- They can articulate why they do what they do, not just what to do

- They maintain progress between sessions without significant backsliding

- They express confidence in their ability to continue independently

The independence conversation¶

Transitioning to independence should be explicit, not assumed. Have a conversation about it.

Coaching in Practice: The Independence Conversation¶

[CHONK: Coaching in Practice - The Independence Conversation]

After 18 months of working together, Alex has lost weight, built consistent exercise habits, and maintained these changes through a job transition and a family health crisis.

Coach: "Alex, I want to talk about something. You've been incredibly consistent for over a year now. You've handled setbacks on your own. You've adapted when things changed. I'm wondering if we should talk about transitioning you to maintenance mode."

Alex: "What does that mean? Are you firing me as a client?"

Coach: laughs "Definitely not. It means I think you've developed the skills to coach yourself most of the time. Instead of weekly sessions, we could move to monthly check-ins. You'd know I'm here if something comes up, but you wouldn't need me every week."

Alex: "Honestly, that sounds right. I feel like I know what to do now. But it's scary to think about doing it alone."

Coach: "That's totally normal. And the reality is, you've been doing it alone most of the time anyway. Our sessions are an hour a week. What happens in the other 167 hours is all you. You've proven you can do this."

Alex: "When you put it that way..."

Coach: "Let's try monthly check-ins for three months. If you need more support, we adjust. If you're sailing, we might even go to quarterly. The goal is to find the minimum support that keeps you thriving." |

Maintenance check-ins versus intensive coaching¶

Even independent clients often benefit from periodic check-ins. These serve different purposes than intensive coaching:

Intensive coaching:

- Weekly frequency

- Active behavior change

- Regular accountability

- Frequent troubleshooting

Maintenance check-ins:

- Monthly to quarterly frequency

- Review and reinforce established patterns

- Early detection of drift

- Celebration of sustained success

- Adjustment for changing life circumstances

Think of maintenance check-ins like dental cleanings. Preventive care that catches small issues before they become big problems.

[CHONK 6: The Practical Toolkit]¶

Self-monitoring without obsession¶

We've established that tracking can be helpful and that it can become problematic. The key is finding the right approach for each client.

Principles of healthy self-monitoring:

- Focus on trends, not individual data points: A sleep score of 72 one night means nothing. A trend of declining sleep scores over two weeks means something.

- Use data to inform decisions, not judge worth: "My HRV is trending down, I should prioritize recovery" is helpful. "My HRV is trending down. I'm failing" is not.

- Take periodic breaks: Encourage clients to go tracker-free for a week periodically. If they can't tolerate this, that's information worth exploring.

- Match tracking intensity to stability: More detailed tracking during behavior change phases; simpler tracking during maintenance.

Research found that self-monitoring was one of the most common and effective behavior change techniques across digital health interventions.33 But the same research noted that most programs lacked components that support long-term maintenance, suggesting that self-monitoring works best as part of a larger system.

Accountability structures that work long-term¶

Accountability works. But different structures work for different people and different phases:

External accountability (coach/group):

- Most helpful during behavior establishment

- Provides structure when internal motivation wavers

- Can create dependency if not transitioned appropriately

Social accountability (friends/family):

- Effective when the social network is supportive

- Can backfire if network members undermine change

- Important to choose accountability partners carefully

Self-accountability (internal systems):

- Essential for long-term independence

- Built through self-monitoring, planning, and self-compassion

- Takes time to develop but is most sustainable

Research on smoking cessation found that peers who smoke dramatically increased relapse risk (OR = 8.64), while each additional program session reduced relapse.34 Environment and engagement both matter.

Community and social support¶

Social support consistently predicts long-term behavior maintenance.8 But not all social support is equal.

Helpful support:

- Encouragement without pressure

- Practical assistance (cooking healthy meals together, exercising together)

- Acceptance of setbacks without judgment

- Modeling healthy behaviors

Unhelpful "support":

- Nagging or criticism

- Competitive comparison

- Enabling old behaviors

- Unsolicited advice

One particularly poignant finding: among widowed older adults, each point of loneliness predicted an additional decline in physical activity, with the effect being about 150 percent greater than in married or unmarried individuals.35 Social connection isn't just nice, it's a physiological need that affects behavior.

Using wearables wisely¶

Wearables can be valuable tools. They can also become expensive anxiety-generators. Help clients use them wisely:

Good use of wearables:

- Noticing trends over time

- Discovering patterns (e.g., "I sleep worse when I drink alcohol")

- Setting gentle reminders to move

- Celebrating progress

Problematic use of wearables:

- Checking data constantly

- Feeling unable to sleep/exercise/function without the device

- Using data to punish oneself

- Prioritizing scores over actual well-being

Remember: approximately 45 percent of wearable users report positive effects on sleep and stress, while only about 4.5 percent report negative effects.22 For most people, these tools help. But your job is to identify the minority for whom they don't, and help them find different strategies.

"Big Rocks First"¶

This concept comes from time management but applies perfectly to health: Put the big rocks in first, or they won't fit.

The big rocks for longevity:

1. Sleep (7-9 hours)

2. Movement (150+ minutes/week)

3. Nutrition (adequate protein, vegetables, reasonable portions)

4. Connection (meaningful relationships)

5. Stress management (some system that works for them)

The pebbles and sand:

- Specific supplement protocols

- Precise macronutrient ratios

- Optimal workout timing

- Biohacking techniques

If a client is sleeping poorly but asking about their cold plunge protocol, redirect them. The fundamentals matter more than the optimizations. Always.

Coaching in Practice: The Quarterly Check-In Template¶

[CHONK: Coaching in Practice - The Quarterly Check-In Template]

For maintenance-phase clients, a structured quarterly check-in can help identify drift before it becomes relapse. Use this template:

Part 1: The Big Rocks Review (5 minutes)

"On a scale of 1-10, how would you rate each of these over the past three months?"

- Sleep quality

- Movement/exercise

- Nutrition

- Social connection

- Stress management

Part 2: What's Working? (5 minutes)

"What habits or systems have been working well? Let's make sure we don't accidentally change these."

Part 3: What's Slipping? (5 minutes)

"Anything that's started to drift or feels harder to maintain? Let's catch small issues before they become big ones."

Part 4: Life Changes (5 minutes)

Any major changes coming up: job, family, health, travel? Let's think about how to prepare.

Part 5: Next Quarter Focus (5 minutes)

"What's ONE thing you want to focus on improving over the next three months?"

Key takeaway: This 25-minute structure creates accountability without overwhelming. It's maintenance, not intensive coaching. |

Key takeaways¶

Let's summarize the core principles for supporting behavior change over the long haul:

-

Think in decades, not weeks. Long-term success comes from consistency over intensity. Help clients build sustainable systems rather than heroic short-term efforts.

-

Habits take longer than you think. The median time to habit formation is about two months, not three weeks. Set realistic expectations.

-

Anchor new behaviors to existing routines. Habit stacking, connecting new behaviors to reliable existing cues, accelerates automaticity.

-

Watch for wellness perfectionism. Some clients' drive to optimize can become counterproductive anxiety. Know the signs, and know when to refer.

-

Expect setbacks. Behavior change isn't linear. Help clients distinguish lapses from relapses and respond to setbacks with compassion and problem-solving.

-

Build toward independence. Your goal is to develop self-coaching skills, not create dependence. Transition clients to maintenance as they develop autonomy.

-

Fundamentals first. Sleep, movement, nutrition, and connection deliver the vast majority of health benefits. Advanced optimizations matter only after these are solid.

Study Guide Questions¶

[CHONK: Study guide questions]

Here are some questions that can help you think through the material and prepare for the chapter exam. They're optional, but we recommend you try answering at least a few as part of your active learning process.

-

What is the "adherence paradox," and why does it matter for longevity coaching?

-

According to research, approximately how long does it take to form a health habit? How does this differ from popular beliefs?

-

What is "habit stacking," and how would you explain it to a client?

-

What are three signs that a client's relationship with health tracking might have become problematic?

-

What is the difference between a "lapse" and a "relapse"? Why does this distinction matter?

-

What role should a coach's response play when a client returns after a setback?

-

What are three signs that a client might be ready for independent maintenance rather than intensive coaching?

-

Why is social support important for long-term behavior maintenance? What makes social support helpful versus unhelpful?

Chapter exam¶

Instructions: Select the best answer for each question. This is an open-book exam. You're encouraged to refer back to the chapter as needed.

1. According to research, what is the median time required to form a health habit?

A) 21 days

B) 30 days

C) 59-66 days

D) 6 months

2. Which of the following best describes the "adherence paradox"?

A) People who try harder always get better results

B) Consistent moderate adherence over years beats perfect short-term adherence that burns out

C) Adherence matters less than the specific intervention chosen

D) Most people adhere better to complex protocols than simple ones

3. "Habit stacking" involves:

A) Doing multiple exercises in one session

B) Connecting a new behavior to an existing routine as a cue

C) Tracking multiple health metrics simultaneously

D) Increasing behavior intensity every week

4. Orthosomnia refers to:

A) Optimal sleep achieved through proper sleep hygiene

B) An obsessive pursuit of perfect sleep driven by tracker metrics

C) A type of sleep disorder caused by stress

D) A meditation technique for better sleep

5. Which of the following is a sign that a client's health tracking may have become problematic?

A) They check their data once per week

B) They feel significant anxiety when unable to track or when data is missing

C) They use data to notice trends over time

D) They take periodic breaks from tracking

6. When a client returns after a setback, what should a coach do FIRST?

A) Immediately create a new, more intensive plan

B) Analyze what went wrong and identify the specific failure point

C) Provide emotional validation and normalize setbacks

D) Recommend the client restart from the beginning

7. The difference between a "lapse" and a "relapse" is:

A) A lapse is longer than a relapse

B) A lapse is a temporary slip while a relapse is returning to old patterns entirely

C) A lapse requires professional help while a relapse doesn't

D) There is no meaningful difference between the terms

8. Research on retirement and health behaviors suggests that:

A) Retirement always leads to worse health behaviors

B) Retirement can create opportunities for positive behavior change

C) Health behaviors cannot be changed after retirement

D) Only people who retire early improve their health behaviors

9. Progressive autonomy in coaching means:

A) Giving clients complete independence from the first session

B) Never reducing coaching frequency regardless of client progress

C) Building self-coaching skills so clients eventually need less support

D) Transferring clients to different coaches over time

10. According to the "Big Rocks First" principle, coaches should:

A) Focus on advanced optimization techniques before basics

B) Ensure fundamentals (sleep, movement, nutrition, connection) are solid before addressing advanced interventions

C) Only work on one health behavior at a time

D) Prioritize whatever the client is most interested in

11. Which of the following is true about behavior change research?

A) Change follows a straight upward line with consistent progress

B) Setbacks and reversals are abnormal signs of client failure

C) Change is non-linear with typical patterns of progress and setback

D) Most people successfully change behaviors on their first attempt

12. Signs that warrant referring a client to a mental health professional include:

A) Occasional frustration with slow progress

B) Tracking behaviors significantly interfering with work, relationships, or daily function

C) Mild disappointment when missing a workout

D) Asking questions about nutrition

13. Early engagement in behavior change programs:

A) Has no relationship to long-term outcomes

B) Is one of the strongest predictors of long-term success

C) Matters only for the first week

D) Is less important than program content

14. Healthy self-monitoring is characterized by:

A) Checking data constantly throughout the day

B) Focusing on individual data points rather than trends

C) Using data to inform decisions without judging self-worth

D) Inability to tolerate any breaks from tracking

15. The best motivation framing for long-term behavior maintenance appears to be:

A) Weight loss goals

B) External rewards

C) Stress reduction and how you want to feel

D) Competition with others

[CHONK: Works Cited]

Deep Dives¶

Want to go deeper? These supplemental articles explore key topics from this chapter in more detail.

- Habit Formation Science: 59-66 day timeline, cue-routine-reward mechanics

References¶

-

Roordink EM, Steenhuis IH, Kroeze W, Chinapaw MJ, van Stralen MM. Perspectives of health practitioners and adults who regained weight on predictors of relapse in weight loss maintenance behaviors: a concept mapping study. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine. 2021;10(1):22-40. doi:10.1080/21642850.2021.2014332

-

Turkkila E, Pekkala T, Merikallio H, Merikukka M, Heikkilä L, Hukkanen J, et al. Five-year follow-up of a randomized weight loss trial on a digital health behaviour change support system. International Journal of Obesity. 2025;49(5):949-953. doi:10.1038/s41366-025-01742-4

-

Thomas JG, Bond DS, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR. Weight-Loss Maintenance for 10 Years in the National Weight Control Registry. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;46(1):17-23. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2013.08.019

-

Ma H, Wang A, Pei R, Piao M. Effects of habit formation interventions on physical activity habit strength: meta-analysis and meta-regression. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2023;20(1). doi:10.1186/s12966-023-01493-3

-

Hershfield HE. Future self‐continuity: how conceptions of the future self transform intertemporal choice. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2011;1235(1):30-43. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06201.x

-

Mitchell NS, Polsky S, Catenacci VA, Furniss AL, Prochazka AV. Up to 7 Years of Sustained Weight Loss for Weight-Loss Program Completers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2015;49(2):248-258. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.011

-

Lawlor ER, Hughes CA, Duschinsky R, Pountain GD, Hill AJ, Griffin SJ, et al. Cognitive and behavioural strategies employed to overcome “lapses” and prevent “relapse” among weight‐loss maintainers and regainers: A qualitative study. Clinical Obesity. 2020;10(5). doi:10.1111/cob.12395

-

NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. Promoting the Science and Practice of Health Behavior Maintenance – Workshop 4: Summary. 2024. https://obssr.od.nih.gov/about/health-behavior-maintenance/workshop-4-summary

-

Leung AWY, Chan RSM, Sea MMM, Woo J. An Overview of Factors Associated with Adherence to Lifestyle Modification Programs for Weight Management in Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017;14(8):922. doi:10.3390/ijerph14080922

-

Sawamoto R, Nozaki T, Nishihara T, Furukawa T, Hata T, Komaki G, et al. Predictors of successful long-term weight loss maintenance: a two-year follow-up. BioPsychoSocial Medicine. 2017;11(1). doi:10.1186/s13030-017-0099-3

-

Cheng AL, Dwivedi ME, Martin A, Leslie CG, Fulkerson DE, Bonner KH, et al. Predictors of Progressing Toward Lifestyle Change Among Participants of an Interprofessional Lifestyle Medicine Program. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2023. doi:10.1177/15598276231222868

-

Singh B, Murphy A, Maher C, Smith AE. Time to Form a Habit: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Health Behaviour Habit Formation and Its Determinants. Healthcare. 2024;12(23):2488. doi:10.3390/healthcare12232488

-

Stojanovic M, Grund A, Fries S. Context Stability in Habit Building Increases Automaticity and Goal Attainment. Frontiers in Psychology. 2022;13. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.883795

-

Stecher C, Sullivan M, Huberty J. Using Personalized Anchors to Establish Routine Meditation Practice With a Mobile App: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2021;9(12):e32794. doi:10.2196/32794

-

Gasana J, O’Keeffe T, Withers TM, Greaves CJ. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the long-term effects of physical activity interventions on objectively measured outcomes. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1). doi:10.1186/s12889-023-16541-7

-

Baron KG, Abbott S, Jao N, Manalo N, Mullen R. Orthosomnia: Are Some Patients Taking the Quantified Self Too Far?. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2017;13(02):351-354. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6472

-

Jahrami H, Trabelsi K, Husain W, Ammar A, BaHammam AS, Pandi-Perumal SR, et al. Prevalence of Orthosomnia in a General Population Sample: A Cross-Sectional Study. Brain Sciences. 2024;14(11):1123. doi:10.3390/brainsci14111123

-

Kozlowska M, Kuty-Pachecka M. When perfectionists adopt health behaviors: perfectionism and self-efficacy as determinants of health behavior, anxiety and depression. Current Issues in Personality Psychology. 2022. doi:10.5114/cipp/156145

-

Pratt VB, Hill AP, Madigan DJ. A longitudinal study of perfectionism and orthorexia in exercisers. Appetite. 2023;183:106455. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2023.106455

-

Bills E, Muir SR, Stackpole R, Egan SJ. Perfectionism and compulsive exercise: a systematic review and preliminary meta-analysis. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity. 2025;30(1). doi:10.1007/s40519-024-01704-1

-

Ryan J, Edney S, Maher C. Anxious or empowered? A cross-sectional study exploring how wearable activity trackers make their owners feel. BMC Psychology. 2019;7(1). doi:10.1186/s40359-019-0315-y

-

Dion K, Porteous M, Kendzerska T, Nixon A, Lee E, de Zambotti M, et al. Sleep, Health Care–Seeking Behaviors, and Perceptions Associated With the Use of Sleep Wearables in Canada: Results From a Nationally Representative Survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2025;27:e68816-e68816. doi:10.2196/68816

-

Österman S, Axelsson E, Forsell E, Svanborg C, Lindefors N, Hedman-Lagerlöf E, et al. Effectiveness and prediction of treatment adherence to guided internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for health anxiety: A cohort study in routine psychiatric care. Internet Interventions. 2024;38:100780. doi:10.1016/j.invent.2024.100780

-

DiClemente CC, Crisafulli MA. Relapse on the Road to Recovery: Learning the Lessons of Failure on the Way to Successful Behavior Change. Journal of Health Service Psychology. 2022;48(2):59-68. doi:10.1007/s42843-022-00058-5

-

Hayes JF, Wing RR, Unick JL, Ross KM. Behaviors and psychological states associated with transitions from regaining to losing weight. Health Psychology. 2022;41(12):938-945. doi:10.1037/hea0001224

-

MILLER J, NELSON T, BARR-ANDERSON DJ, CHRISTOPH MJ, WINKLER M, NEUMARK-SZTAINER D. Life Events and Longitudinal Effects on Physical Activity: Adolescence to Adulthood. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2019;51(4):663-670. doi:10.1249/mss.0000000000001839

-

Verplanken B, Roy D. Empowering interventions to promote sustainable lifestyles: Testing the habit discontinuity hypothesis in a field experiment. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2016;45:127-134. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.11.008

-

Yi M, et al.. Transition to retirement impact on health and lifestyle habits: Analysis from a nationwide Italian cohort. BMC Public Health; 2021. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-021-11670-3

-

Pan F, et al.. Understanding the effect of retirement on health behaviors in China: Causality, heterogeneity and time-varying effect. Front Public Health; 2022. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9421064/

-

Alonso WW, Kupzyk K, Norman J, Bills SE, Bosak K, Dunn SL, et al. Negative Attitudes, Self-efficacy, and Relapse Management Mediate Long-Term Adherence to Exercise in Patients With Heart Failure. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2021;55(10):1031-1041. doi:10.1093/abm/kaab002

-

Schmidt SK, et al.. Maintenance of positive outcomes after lifestyle interventions. Int J Environ Res Public Health; 2020. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7602059/

-

Zhu Y, Long Y, Wang H, Lee KP, Zhang L, Wang SJ. Digital Behavior Change Intervention Designs for Habit Formation: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2024;26:e54375. doi:10.2196/54375

-

Joo H, Cho MH, Cho Y, Joh H, Kim JW. Predictors of long-term smoking cessation among smokers enrolled in a university smoking cessation program. Medicine. 2020;99(5):e18994. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000018994

-

Pollak C, Verghese J, Blumen HM. Loneliness predicts decreased physical activity in widowed but not married or unmarried individuals. Frontiers in Public Health. 2024;12. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2024.1295128