Unit 3: Advanced Topics & Disease Prevention¶

Chapter 3.18: Neuroprotection¶

[CHONK: 1-minute summary]

[CHONK: Brain Health Across the Lifespan]

Why brain health matters for longevity¶

When people think about living longer, they often imagine more years of physical capability: more hikes, more time with grandchildren, more independence. But there's a fear that haunts many clients, often unspoken: What if my body outlasts my mind?

For most people, cognitive decline represents the worst-case aging scenario: losing the ability to recognize loved ones, recall precious memories, and maintain independence in daily life. These fears run deep, and they're not unfounded: dementia affects approximately 55 million people worldwide, with nearly 10 million new cases annually.

As a longevity coach, you'll encounter clients who want to discuss brain health but don't know how to bring it up. You'll work with people who have watched parents or grandparents decline cognitively and wonder if the same fate awaits them. Understanding the science of neuroprotection—and the limits of what we can promise—will help you support these clients with both compassion and honesty.

While we can't guarantee prevention of cognitive decline or dementia, substantial evidence suggests that lifestyle factors significantly influence brain health across the lifespan. Your role as a coach is to help clients take meaningful action on what's within their control while maintaining realistic expectations.

The good news: modifiable risk factors¶

The 2024 Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention—a major international review of the evidence—concluded that addressing 14 modifiable risk factors could potentially prevent or delay approximately 45 percent of dementia cases worldwide.

Let that number sink in: not 5 percent, not 10 percent, but nearly half.

These modifiable risk factors span the entire lifespan:

Early life:

- Lower educational attainment

Midlife:

- Hearing loss

- Traumatic brain injury

- Hypertension

- High LDL cholesterol (newly added in 2024)

- Excessive alcohol consumption

- Obesity

- Smoking

Later life and across the lifespan:

- Depression

- Social isolation

- Physical inactivity

- Diabetes

- Air pollution

- Untreated vision loss (newly added in 2024)

The 2024 update added two risk factors based on new evidence: high LDL cholesterol in midlife (accounting for approximately 7 percent of attributable risk) and untreated vision loss in later life (approximately 2 percent).

What these numbers mean¶

When researchers say 45 percent of dementia cases could be "prevented or delayed," they're using a concept called population attributable fraction: the proportion of cases that might not occur if these risk factors were eliminated. This is a theoretical maximum based on current evidence, assuming the relationships are causal.

Important caveats:

- These are observational associations; causality isn't definitively proven for all factors

- A 2023 study using genetic analysis (Mendelian randomization) found limited genetic evidence supporting causal effects for some risk factors, suggesting some associations may reflect confounding

- Risk factors overlap and interact. You can't simply add the percentages together

- Individual risk reduction will vary based on genetics, other factors, and timing of intervention

- Still, even if the true preventable proportion is lower, the evidence strongly suggests that lifestyle choices matter for brain health, and that's something coaches can work with.

If all those percentages and caveats feel a bit abstract, that's OK. The key takeaway is that everyday habits really do matter for brain health, even if we can't pin down an exact number for any one person.

What we can and can't promise¶

No lifestyle intervention has been proven in randomized trials to definitively prevent dementia. The evidence for modifiable risk factors comes primarily from observational studies. People who exercise more, eat healthier, stay socially connected, and manage cardiovascular risk tend to have lower rates of cognitive decline and dementia.

Does this mean exercise causes better brain health, or that healthier people are simply more likely to exercise? We can't be certain from observational data alone. The relationships are likely bidirectional and influenced by many factors.

What we CAN say to clients:

- "The evidence suggests that these lifestyle factors are associated with better cognitive outcomes"

- "We can focus on reducing modifiable risk factors"

- "These interventions benefit your overall health regardless of brain-specific effects"

- "We're optimizing what's within your control"

What we should NOT say:

- "This will prevent Alzheimer's"

- "Following this program guarantees you won't get dementia"

- "If you do everything right, you're protected"

- The reframe: We optimize, we don't guarantee. And fortunately, everything that supports brain health also supports overall health, so there's no downside to focusing on these factors. If that feels like a lot to hold as a coach, remember your role is to support clients in small, realistic changes, not to single-handedly prevent disease.

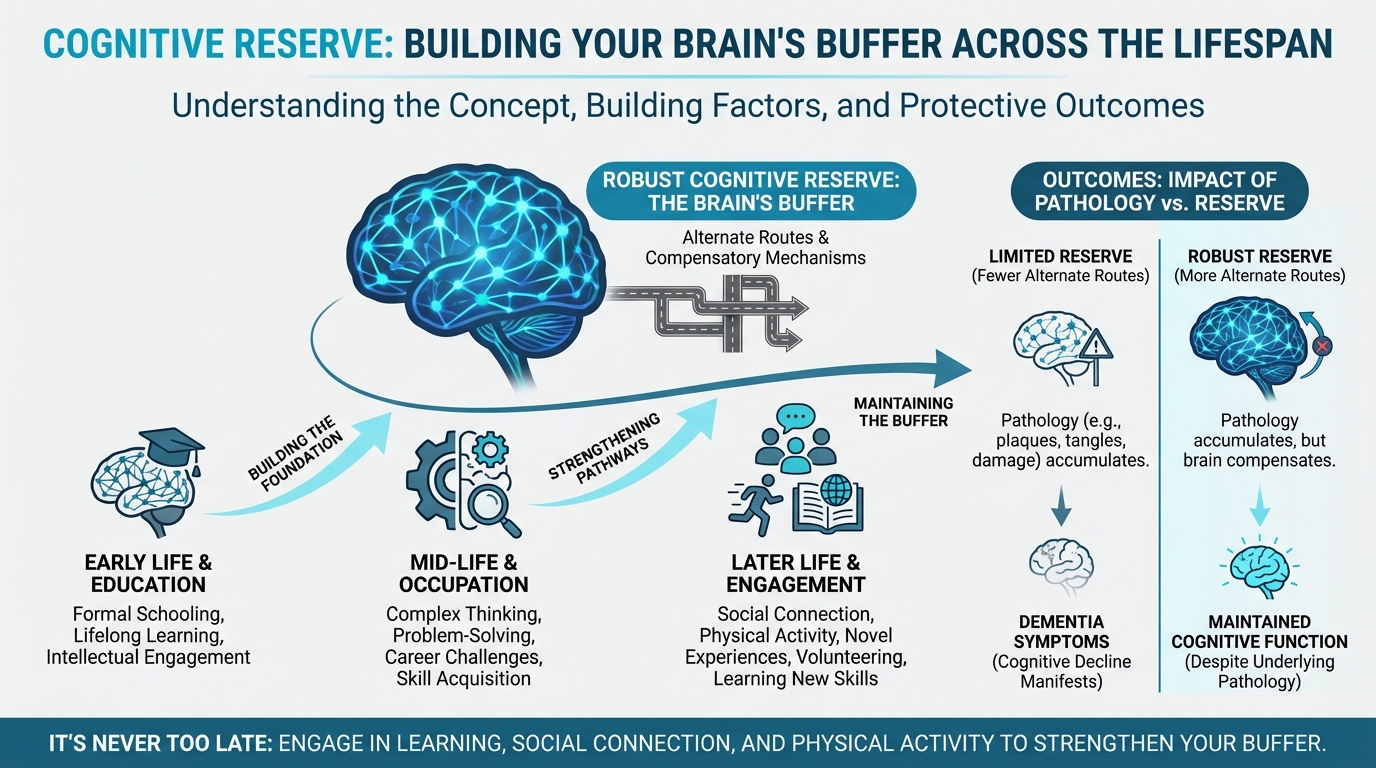

Cognitive reserve: building your brain's buffer¶

One of the most hopeful concepts in brain health research is cognitive reserve: the brain's ability to improvise and find alternate ways of completing a task when faced with damage or age-related changes.

Think of it like having multiple routes to the same destination. If one road is blocked, you can take another. People with higher cognitive reserve have more "alternate routes," more neural pathways and connections that can compensate when some are damaged.

Research suggests cognitive reserve is built through:

- Education and lifelong learning: Not just formal schooling, but continued intellectual engagement

- Occupational complexity: Jobs that involve complex thinking, problem-solving, and learning

- Social engagement: Rich social networks and meaningful relationships

- Physical activity: Exercise that challenges both body and mind

- Novel experiences: Learning new skills, traveling, encountering new ideas

The concept of cognitive reserve helps explain why some people with significant brain pathology (visible on autopsy) maintained normal cognitive function during life, while others with less pathology showed dementia symptoms. The difference appears to be the "buffer" built through a lifetime of cognitive engagement.

For coaching, this means: it's never too late to build cognitive reserve. Even in late life, engaging in new learning, social connection, and physical activity may strengthen this buffer. If that feels hopeful but also a little daunting, remember you don't have to overhaul everything at once. You and your clients can build this buffer slowly, one small practice at a time.

The metabolic-cognitive connection¶

As you learned in Chapter 17 on metabolic health, what happens in the body profoundly affects the brain. This is particularly true for metabolic dysfunction.

The brain:

- Uses approximately 20 percent of the body's energy despite being only 2 percent of body weight

- Requires a constant supply of glucose and oxygen

- Is exquisitely sensitive to insulin signaling

- Is vulnerable to vascular damage from hypertension and dyslipidemia

Insulin resistance, the metabolic dysfunction underlying Type 2 diabetes, doesn't just affect blood sugar. It affects the brain's ability to use glucose efficiently, increases inflammation, and may contribute to the accumulation of abnormal proteins associated with Alzheimer's disease.

This connection is so strong that some researchers have called Alzheimer's "Type 3 diabetes," though this remains controversial and oversimplifies a complex disease. What's clear is that metabolic health and brain health are deeply intertwined, and interventions that improve one often improve the other.

[CHONK: The Science of Neuroprotection]

Understanding brain health mechanisms¶

To support clients in their brain health journey, you need a basic understanding of the mechanisms involved, not to diagnose or treat, but to explain why certain interventions might help and to answer common questions.

BDNF: Miracle-Gro for the brain¶

You encountered BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) in Chapter 2.9 when we discussed how exercise benefits the brain. Here's a quick refresher and some additional context.

BDNF is a protein that acts like fertilizer for neurons (brain cells). It:

- Supports the survival of existing neurons

- Encourages the growth of new neurons (neurogenesis), particularly in the hippocampus (the brain's memory center)

- Promotes the formation of new connections between neurons (synapses)

- Helps with learning and memory consolidation

BDNF levels naturally decline with age, and lower levels are associated with depression, cognitive decline, and neurodegenerative diseases. The good news: certain lifestyle factors can boost BDNF production.

What increases BDNF:

- Exercise (particularly aerobic and resistance training)

- Learning new skills

- Social engagement

- Certain dietary patterns (especially those rich in flavonoids and omega-3 fatty acids)

- Quality sleep

What decreases BDNF:

- Chronic stress

- Sedentary behavior

- Inflammatory diet

- Social isolation

- Poor sleep

Meta-analyses confirm that exercise reliably increases peripheral (blood) BDNF levels, with moderate-intensity resistance training showing particularly large effects in some studies. Functional training—exercise that mimics real-world movements—may produce larger BDNF increases than isolated aerobic exercise alone.

The glymphatic system: your brain's overnight cleanup crew¶

As you learned in Chapter 2.11 on sleep optimization, the brain has its own waste clearance system called the glymphatic system. This system is most active during sleep, particularly during deep (slow-wave) sleep.

Rather than repeating that material, here's what's important for neuroprotection:

The glymphatic system clears metabolic waste from the brain, including amyloid-beta, a protein that accumulates in Alzheimer's disease. Poor sleep disrupts this clearance process, potentially allowing harmful substances to accumulate.

Key point for clients: Sleep isn't just rest. It's when your brain takes out the trash. Chronic sleep deprivation doesn't just leave you tired, it may allow waste products to build up in brain tissue.

For more detail on the glymphatic system and sleep optimization strategies, refer clients and yourself back to Chapter 2.11.

Inflammation and the brain¶

Chronic low-grade inflammation—the type associated with obesity, metabolic dysfunction, poor diet, chronic stress, and sedentary behavior—affects the brain in multiple ways:

- Crosses the blood-brain barrier and activates brain immune cells (microglia)

- Disrupts normal neuronal function

- May contribute to the formation of abnormal protein deposits

- Impairs BDNF signaling

- Damages blood vessels that supply the brain

This is why interventions targeting inflammation—anti-inflammatory diets, exercise, stress management, quality sleep—may benefit brain health even if they don't directly target the brain itself.

The vascular hypothesis: heart health is brain health¶

The brain depends entirely on blood vessels to deliver oxygen and nutrients. Anything that damages blood vessels—hypertension, high cholesterol, diabetes, smoking—damages the brain.

This vascular connection explains why:

- Cardiovascular disease and dementia share many risk factors

- Mid-life hypertension is a significant dementia risk factor

- High LDL cholesterol in midlife (newly recognized in 2024) increases dementia risk

- Stroke can cause vascular dementia directly

The practical implication: Much of what we do to protect the heart also protects the brain. Cardiovascular risk management isn't separate from brain health. It IS brain health.

A brief word on Alzheimer's pathophysiology¶

You may wonder about amyloid plaques and tau tangles, the abnormal protein deposits found in Alzheimer's disease. Here's what coaches need to know:

Alzheimer's disease is characterized by:

- Accumulation of amyloid-beta protein into plaques outside neurons

- Accumulation of tau protein into tangles inside neurons

- Progressive loss of synapses and neurons

However, these pathological changes can begin 20+ years before symptoms appear, and some people accumulate significant pathology without ever developing dementia (this is where cognitive reserve comes in).

Current drug treatments targeting amyloid have shown modest effects at best, and the field is moving toward earlier intervention and multifactorial approaches, which aligns perfectly with the lifestyle-focused prevention strategies we'll discuss.

What coaches don't need to know: The detailed molecular mechanisms, genetic testing interpretation, or treatment protocols. Leave that to neurologists and geriatricians. Focus on what clients can actually do.

Coaching in practice: Explaining brain science accessibly¶

When clients ask about brain mechanisms, your goal is to keep things simple, accurate, and reassuring.

What NOT to do:

❌ Launch into a long lecture about BDNF, glymphatic flow, and neurodegeneration.

Why it doesn't work: Most clients just want a clear picture, not a mini biology class.

What TO do:

✅ Use short, everyday metaphors and check that your explanation lands.

Client: Why does exercise actually help my brain?

Coach: Great question. When you move your body, you make more of a protein called BDNF. You can think of it like fertilizer for brain cells, it helps them stay healthy and grow new connections, especially in memory areas. Does that picture make sense?

Client: Yeah, that helps. Fertilizer for my brain, I can remember that.

Client: What about sleep? Why is that so important for my brain?

Coach: While you sleep, your brain turns on a cleanup system that clears out waste products. It's like having a night crew that comes in to clean an office, but they can only work when everyone goes home. If you don't get enough sleep, the trash piles up.

Client: And inflammation? Does that really affect my brain too?

Coach: Yes. Chronic inflammation can cross into the brain and disrupt normal function. The good news is that many things that reduce inflammation in the body, like good food, regular movement, sleep, and stress management, also protect the brain.

[CHONK: Evidence-Based Brain Health Strategies]

What actually works for brain health¶

We'll look at specific interventions, their evidence quality, and practical applications for coaching. Throughout this section, we'll be explicit about what the evidence shows and where uncertainty remains.

Exercise: the #1 brain health intervention¶

Evidence level: Strong (for association and cognitive benefits in those with impairment); Moderate-to-Strong (for prevention in healthy adults)

If you could only recommend one thing for brain health, it would be exercise. The evidence is strong and multifaceted.

What the research shows:

For cognitive function:

- Meta-analyses consistently show that exercise improves cognitive function, particularly in older adults with existing cognitive impairment

- A 2025 umbrella review in the British Journal of Sports Medicine concluded there's strong evidence that exercise—even at light intensity—benefits cognition, memory, and executive function across populations

- Combined aerobic and resistance training shows a pooled effect size (Hedges' g) of approximately 0.32 for cognitive improvement, a small-to-moderate effect

For dementia risk:

- The highest levels of physical activity are associated with 26-40 percent lower dementia risk compared to the least active

- A dose-response relationship exists: every 10 MET-hours per week of additional activity is associated with approximately 15 percent lower Alzheimer's risk

- One large UK Biobank analysis found that dementia risk reduction became significant only above 300 minutes per week of moderate-to-vigorous activity

Dose and type:

The evidence suggests:

| Parameter | Recommendation | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum effective dose | 150 minutes/week moderate activity | Associated with some benefit |

| Optimal for brain health | 300+ minutes/week moderate activity, or equivalent | Larger risk reduction seen at higher doses |

| Type | Combined aerobic + resistance | Most consistent benefits (effect size ≈0.32) |

| Intensity | Vigorous activity may contribute disproportionately | UK Biobank: vigorous activity contributed ~79% of protective effect |

Dual-task activities:

Particularly promising for brain health are "dual-task" activities: physical exercise combined with cognitive challenges.

- Walking while having a conversation

- Dance classes (learning sequences while moving)

- Sports requiring strategy and movement

- Exercise video games ("exergaming")

Multiple studies show dual-task training produces greater cognitive improvements than single-task exercise alone, particularly for executive function and daily functioning.

| For DIY Learners |

|---|

| Applying this to yourself: Your brain health is built daily through the same fundamentals we've covered throughout this course: exercise (especially combined cardio + strength), sleep, nutrition, stress management, and social connection. If you're worried about cognitive decline, don't reach for nootropic supplements—reach for a walk with a friend, a challenging new skill to learn, and 7+ hours of sleep. These have far better evidence than any brain-boosting pill. |

Practical application for coaching:

- Any movement is better than none, don't let perfect be the enemy of good

- Build toward 300+ minutes/week for clients motivated to optimize brain health

- Include both aerobic and resistance training when possible

- Incorporate dual-task elements: walking meetings, dance classes, sports with strategic components

- Vigorous exercise may offer additional benefits, but only if clients can do it safely

Nutrition: the MIND diet and beyond¶

Evidence level: Moderate (strong observational data, mixed RCT results)

The MIND diet (Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay) was specifically designed to support brain health, combining elements of the Mediterranean and DASH diets with foods shown in research to benefit cognition.

Core components of the MIND diet:

Emphasized foods:

- Green leafy vegetables (at least 6 servings/week)

- Other vegetables (at least 1 serving/day)

- Berries, especially blueberries (at least 2 servings/week)

- Nuts (at least 5 servings/week)

- Whole grains (at least 3 servings/day)

- Fish (at least 1 serving/week)

- Beans (at least 4 servings/week)

- Poultry (at least 2 servings/week)

- Olive oil as primary cooking oil

- Wine (1 glass/day, optional and controversial)

Limited foods:

- Red meat (less than 4 servings/week)

- Butter/margarine (less than 1 tablespoon/day)

- Cheese (less than 1 serving/week)

- Pastries/sweets (less than 5 servings/week)

- Fried/fast food (less than 1 serving/week)

What the research shows:

Observational studies:

- Higher MIND diet adherence is consistently associated with slower cognitive decline and lower dementia risk

- A meta-analysis of seven cohorts (n=26,103) found each 1 standard deviation increase in MIND score predicted 0.042 units higher global cognition

- One large study (JAMA Psychiatry 2023) found highest adherence associated with approximately 17 percent lower incident dementia risk

Randomized controlled trials:

- A 3-year RCT published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2023) found no significant cognitive difference between MIND diet and control diet groups

- However, both groups in this trial improved their diets, potentially diluting the effect

- Multidomain trials that include MIND diet plus other interventions (like the U.S. POINTER trial) show more promising results

Putting the evidence together:

The MIND diet appears beneficial based on observational data, but the only dedicated RCT showed null results over 3 years. This doesn't mean the diet doesn't work. It may mean:

- Effects take longer than 3 years to manifest

- Diet-alone interventions are insufficient; multidomain approaches may be needed

- The comparison group also improved their diet, reducing the contrast.

If that mix of 'promising but not definitive' feels a bit frustrating, you're not alone. Coaches (and clients) often wish the science were clearer, but learning to work with imperfect evidence is part of being an effective longevity coach.

Practical application:

Rather than rigidly prescribing the MIND diet, focus on the key principles:

1. More vegetables, especially leafy greens. These are consistently associated with slower cognitive decline

2. Regular berries, particularly blueberries, rich in brain-protective flavonoids

3. Fatty fish, source of omega-3 fatty acids (see supplements section)

4. Nuts, olive oil, whole grains: Mediterranean-style eating patterns

5. Less processed food, fried food, added sugars

Sleep: when your brain cleans house¶

Evidence level: Moderate-to-Strong

Sleep's importance for brain health is covered extensively in Chapter 2.11. Here are the key points relevant to neuroprotection:

- The glymphatic system clears brain waste most effectively during deep sleep

- Chronic short sleep (less than 7 hours) is associated with increased dementia risk

- Sleep disorders like obstructive sleep apnea are risk factors for cognitive decline

- Sleep consolidates memories and supports neuroplasticity

Coach's role:

- Screen for sleep concerns using basic questions

- Support sleep hygiene improvements (Chapter 2.11)

- Refer to medical evaluation for suspected sleep disorders

Social connection and purpose¶

Evidence level: Moderate (consistent observational data, limited intervention trials)

One of the most important—and often overlooked—brain health factors is social connection.

What the research shows:

Social isolation and dementia risk:

- The largest meta-analysis to date (n=608,561) found loneliness increases all-cause dementia risk by approximately 31 percent

- Alzheimer's disease risk increased by 39 percent, and vascular dementia risk by 74 percent

- Social isolation (objectively measured) is associated with approximately 28 percent higher hazard of dementia over 9 years

- Even "digital isolation", limited internet/electronic communication, is associated with 36 percent higher dementia risk

Purpose in life:

- Higher purpose in life is associated with lower likelihood of dementia (odds ratio approximately 0.85)

- Purpose appears to provide resilience against cognitive decline even in the presence of brain pathology

- A 28-year prospective study found higher purpose at midlife predicts better cognition in later life

Mechanisms:

Social connection likely protects cognition through multiple pathways:

- Cognitive stimulation from conversation and engagement

- Stress buffering (social support reduces cortisol and stress responses)

- Increased BDNF (emotional support is associated with higher BDNF levels)

- Oxytocin release from positive social interactions

- Reduced depression (a dementia risk factor)

Practical application:

- Assess social connection as part of Deep Health evaluation

- Help clients identify opportunities for meaningful social engagement

- Support purpose clarification: what gives their life meaning?

- Watch for isolation as a warning sign, especially in retirement, widowhood, or relocation

- Consider group-based interventions when available (walking groups, classes, volunteer work)

Coaching in practice: The client who dismisses social connection¶

You'll likely hear some version of this: "I'm an introvert. I don't need other people."

What NOT to do:

❌ Jump in with a lecture about studies on loneliness and dementia risk.

Why it doesn't work: Clients can feel judged or pressured, and it reinforces the idea that connection only "counts" if it looks a certain way.

What TO do:

✅ Validate their temperament and explore what meaningful connection could look like for them.

Client: I'm an introvert. I don't need other people.

Coach: That makes sense. Social health doesn't mean being the life of the party or having a huge circle of friends. It's more about having a few relationships that feel meaningful and supportive. When you think about your life right now, which relationships feel most important to you?

Client: Probably my sister, and one friend from work.

Coach: Great. We can work with that. Quality matters more than quantity. How might you nurture those relationships in ways that feel comfortable for your personality?

Cognitive stimulation and lifelong learning¶

Evidence level: Moderate for cognitive benefits; Limited for far-transfer to real-world function

"Use it or lose it" has some truth, but the nuance matters.

What the research shows:

Cognitive training:

- Working memory training reliably improves performance on trained tasks (effect size approximately 0.34)

- However, far-transfer, improvement in untrained tasks and real-world function, is generally small or absent

- Commercial "brain games" (like Lumosity) show little evidence of real-world cognitive benefits

- Training with everyday, functional cognitive tasks shows better transfer than abstract brain games

Novel learning:

- Learning new skills—particularly complex skills involving multiple domains—appears more beneficial than repetitive "brain exercises"

- Activities that combine cognitive, physical, and social elements (like dance classes, learning an instrument, or group language learning) may offer multiple benefits

What this means in practice:

Brain games are unlikely to protect against dementia, despite marketing claims. (The FTC actually sued Lumosity for deceptive advertising.) However, staying cognitively engaged—especially through novel, meaningful activities—appears to help maintain cognitive function.

Practical application:

Instead of prescribing brain games, encourage:

1. Learning new skills: language, music, art, crafts

2. Activities combining multiple elements: dance (physical + cognitive + social), group classes, sports with strategic components

3. Reading and engaging with complex material

4. Meaningful hobbies that challenge thinking

5. Educational pursuits at any age

Tell clients: "Learning a new language or instrument will likely benefit your brain more than any brain-training app, and it's probably more enjoyable too."

Supplements for brain health¶

Evidence level: Modest for omega-3s; Preliminary for creatine

Clients frequently ask about supplements for brain health. The research paints a more modest picture than many headlines suggest:

Omega-3 fatty acids (DHA/EPA):

What the research shows:

- Umbrella reviews of trials show a small but statistically significant improvement in global cognition (effect size approximately 0.16) with EPA+DHA supplementation in older adults without dementia

- Observational data consistently links higher omega-3 intake with lower dementia risk. One analysis found long-term supplement use associated with 64 percent lower Alzheimer's risk

- Effects appear more pronounced for executive function and at doses around 500-2000 mg/day

- Benefits may depend on baseline omega-3 status and genetics (APOE status)

Practical recommendation:

- Encourage fatty fish consumption (2+ servings/week)

- If supplementing, 500-2000 mg combined EPA+DHA is the range studied

- Set realistic expectations: effects are modest, not dramatic

- Priority should remain on foundational interventions (exercise, sleep, diet pattern)

Creatine:

What the research shows:

- Meta-analyses show small improvements in memory (effect size approximately 0.31) and attention/processing speed

- Benefits appear more pronounced in older adults, vegetarians, or during conditions of energy stress (like sleep deprivation)

- Large RCTs in healthy young adults show little to no effect

- The European Food Safety Authority (2024) concluded that a cause-effect relationship between creatine and improved cognition has not been established

Practical recommendation:

- Not a first-line recommendation for brain health

- May have modest benefits for older adults or those under energy stress

- Standard dose in studies: 3-5 grams/day

- Generally safe with mild GI side effects in some people

For deeper supplement discussion, refer to Chapter 15 on Supplements for Longevity.

Heat therapy and sauna¶

Evidence level: Preliminary (observational data only, limited generalizability)

The longevity protocol mentions sauna use for dementia risk reduction. Research so far suggests:

What the research shows:

- Finnish cohort studies found men who used sauna 4-7 times/week had approximately 66 percent lower dementia risk compared to once-weekly users

- A second Finnish study found 9-12 sauna sessions/month associated with about 50 percent lower risk over the first 20 years of follow-up

- Plausible mechanisms include improved cardiovascular function, heat shock protein activation, and relaxation effects

Critical caveats:

- All evidence is observational and from Finnish populations with specific sauna traditions

- Causality is not established. Frequent sauna users may differ in many ways from infrequent users

- Effects may not generalize to other populations or sauna types

- No randomized trials have tested sauna for cognitive outcomes

If you're feeling unsure about how excited to be about sauna after hearing all of that, that's appropriate. You can be transparent with clients that the data are intriguing but still early, and keep sauna in the "optional extra" category.

Practical recommendation:

- If clients enjoy sauna and have access, it may be a reasonable addition to their wellness routine

- 2-4 sessions weekly at traditional Finnish temperatures (80-100°C/176-212°F) is the range associated with benefits

- Ensure adequate hydration and appropriate precautions

- Do NOT present this as essential or proven for dementia prevention

- This is "nice-to-have, not need-to-have"

[CHONK: The Modifiable Risk Factors]

The Lancet Commission's 14 factors¶

The 2024 Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention provides the most complete framework for understanding modifiable risk factors. Let's examine each factor, its contribution to risk, and coaching implications.

Early life¶

Lower educational attainment (~5% of attributable risk)

This doesn't mean you need advanced degrees. It reflects that early cognitive stimulation and learning build cognitive reserve. For coaching, this means:

- The past can't be changed, but lifelong learning continues to build reserve

- Encourage educational pursuits at any age

- For clients with children/grandchildren, support educational engagement

Midlife¶

Hearing loss (~7% of attributable risk)

Hearing loss is one of the largest modifiable risk factors. The mechanism likely involves reduced cognitive stimulation and increased social isolation when hearing is impaired. Coaching implications:

- Encourage hearing screening for clients over 50

- Support hearing aid use if recommended (many people resist hearing aids)

- Discuss how untreated hearing loss can lead to social withdrawal

Traumatic brain injury

Even "mild" concussions, especially repeated ones, increase dementia risk. For coaches:

- Ask about head injury history

- Support appropriate protective equipment for high-risk activities

- Refer clients with concussion history who notice cognitive changes

Hypertension

High blood pressure in midlife damages brain blood vessels over time. Coaching approach:

- Encourage blood pressure monitoring

- Support lifestyle interventions (exercise, weight management, sodium reduction, stress management)

- Emphasize the brain health connection: it's not just about heart attacks

High LDL cholesterol (~7% of attributable risk, newly added in 2024)

Midlife LDL appears to affect brain health through vascular mechanisms and possibly direct effects on amyloid pathways. Coaching implications:

- Cardiovascular risk management is brain health management

- Support Mediterranean-style eating patterns

- Encourage regular lipid screening and discussion with healthcare providers

Excessive alcohol

Heavy drinking damages the brain directly and indirectly (through liver damage, nutritional deficiencies, falls). The definition of "excessive" varies, but generally:

- More than 14 drinks/week is associated with brain harm

- Even moderate drinking may not be protective, despite earlier claims

- Support clients who want to reduce alcohol consumption

Obesity

Midlife obesity increases dementia risk through multiple pathways: inflammation, insulin resistance, vascular damage, sleep apnea. However:

- The relationship is complex: late-life weight loss may actually be a dementia sign, not a protective factor

- Focus on metabolic health (Chapter 17) rather than just weight

Smoking

Smoking damages brain blood vessels and increases inflammation and oxidative stress. For coaches:

- Support smoking cessation without judgment

- Any reduction helps

- Consider referral to cessation programs

Later life and across the lifespan¶

Depression

Depression both increases dementia risk and can be an early symptom of cognitive decline. The relationship is bidirectional:

- Chronic depression may damage the brain through stress hormones and inflammation

- Early dementia may manifest as depression

- Treatment of depression may reduce dementia risk, though this isn't proven

Coaching role: screen for depression, support mental health help-seeking, never try to treat depression yourself.

Social isolation (~5% of attributable risk)

As discussed earlier, social disconnection significantly increases dementia risk. Coaching approaches:

- Assess social connection as part of routine check-ins

- Help problem-solve barriers to social engagement

- Consider group-based interventions when possible

- Watch for isolation during life transitions (retirement, widowhood, relocation)

Physical inactivity

Covered extensively in the exercise section. Key point: this is likely the most actionable factor for most clients.

Diabetes

Diabetes increases dementia risk through multiple mechanisms: vascular damage, insulin resistance in the brain, inflammation. For coaches:

- Support diabetes prevention through lifestyle (Chapter 17)

- Help clients with diabetes achieve better glycemic control through lifestyle factors

- Emphasize that diabetes management is brain health management

Air pollution

This is harder for individuals to control, but coaches can:

- Encourage indoor air quality improvement (air filters, houseplants)

- Support policy awareness and advocacy if clients are interested

- Suggest outdoor exercise timing to avoid high-pollution periods in affected areas

Untreated vision loss (~2% of attributable risk, newly added in 2024)

Vision loss in later life is associated with approximately 47 percent higher dementia risk. Cataract surgery is associated with 29 percent reduced dementia incidence. For coaches:

- Encourage regular eye exams

- Support addressing vision problems promptly

- Understand that vision loss, like hearing loss, reduces cognitive stimulation and social engagement

A note on genetics¶

Clients often ask about genetic risk, particularly the APOE gene. Here's what coaches need to know:

APOE basics:

- APOE comes in three variants: ε2, ε3, and ε4

- APOE ε4 is associated with increased Alzheimer's risk (about 2-3x higher with one copy, 8-12x higher with two copies)

- However, APOE ε4 is neither necessary nor sufficient for Alzheimer's. Many ε4 carriers never develop dementia, and many without ε4 do

The coaching message:

- Genetics load the gun; lifestyle may pull or not pull the trigger

- Modifiable risk factors matter for everyone, regardless of genetics

- Some evidence suggests lifestyle interventions may be particularly important for those with genetic risk

- Genetic testing interpretation is outside coaching scope. Refer to genetic counselors if clients want testing

For clients interested in genetics and nutrition, Precision Nutrition has a detailed e-book on genetic testing available at: https://www.precisionnutrition.com/genetic-testing-ebook

| Coaching in practice | |

|---|---|

| The 14 factors at a glance | |

| When discussing modifiable risk factors with clients, this simplified breakdown may help: | |

| Cardiovascular factors (protect your blood vessels): | |

| Hypertension, high cholesterol, diabetes, smoking, obesity | |

| Lifestyle factors (what you do every day): | |

| Physical inactivity, excessive alcohol, unhealthy diet, cognitive disengagement | |

| Social-emotional factors (connection and mental health): | |

| Social isolation, depression | |

| Sensory factors (stay connected to the world): | |

| Hearing loss, vision loss | |

| Environmental factors (some harder to control): | |

| Air pollution, traumatic brain injury, lower educational attainment |

[CHONK: Coaching Cognitive Health]

Supporting clients with brain health concerns¶

Brain health discussions require particular sensitivity. Many clients carry deep fears about cognitive decline: watching a parent's dementia, noticing their own memory lapses, worrying about their future. Your role is to provide accurate information, practical support, and appropriate boundaries.

Scope-safe language for cognitive health¶

Remember your scope as a health and wellness coach (Chapter 1.5). You are NOT:

- Diagnosing cognitive impairment or dementia

- Interpreting cognitive test results

- Providing dementia treatment

- Assuring clients they won't get dementia

You ARE:

- Providing evidence-based education about brain health

- Supporting lifestyle behaviors associated with cognitive health

- Helping clients navigate fear and uncertainty

- Recognizing when referral is needed

Language to use:

- "Research suggests that..." (not "this will prevent...")

- "Associated with lower risk" (not "prevents")

- "We can focus on what's within your control"

- "These healthy behaviors benefit you regardless of future cognitive outcomes"

- "If you're concerned about your memory, let's talk about when to see your doctor"

Language to avoid:

- "This will protect you from Alzheimer's"

- "If you follow this program, you won't get dementia"

- "Your memory problems are probably just normal aging" (you can't determine this)

- "You don't need to see a doctor about that" (you can't rule out concerning causes)

Supporting clients with family history¶

Clients with a parent or sibling with dementia often carry significant anxiety. Here's how to support them:

Acknowledge the fear:

"It makes complete sense that you'd be thinking about this. Watching your mother's decline was incredibly difficult, and worrying about your own future is natural."

Provide context:

"Having a parent with Alzheimer's does increase risk, but it's not destiny. Most dementia is not purely genetic. Lifestyle factors play a significant role. Some research suggests lifestyle interventions may be particularly important for those with family history."

Focus on action:

"Rather than focusing on what you can't control, let's work together on what you can. Exercise, sleep, social connection, managing cardiovascular health. These all matter for your overall wellbeing and may support brain health too."

Avoid false reassurance:

Don't say "You'll be fine" or "You won't get dementia." You can't promise that. Instead: "We're going to do everything we can to support your health and give you the best possible foundation."

Handling dementia fear conversations¶

When clients express fear about cognitive decline:

-

Listen fully before responding. Often people need to express fear before they can hear information.

-

Validate the emotion: "These concerns are really common, and they make sense."

-

Explore what's driving the fear: Is it a specific memory lapse? Family history? Recent diagnosis of a friend?

-

Distinguish normal aging from concerning signs:

- Normal: Occasionally forgetting a word, misplacing keys, needing more time to learn new things

-

Concerning: Getting lost in familiar places, difficulty having conversations, personality changes, trouble with familiar tasks

-

Provide accurate information about what's known and unknown.

-

Return focus to what they can do: "Regardless of what the future holds, these healthy behaviors are good for you now and may support your brain health over time."

-

Know when to refer (see below).

When to refer: recognizing warning signs¶

As a coach, you should encourage medical evaluation when clients report:

Memory concerns that:

- Interfere with daily activities

- Are noticed by others (not just the client)

- Represent a change from previous function

- Include forgetting recently learned information, important dates, or events

- Lead to repeatedly asking the same questions

Other cognitive changes:

- Difficulty planning or solving problems

- Trouble completing familiar tasks

- Confusion about time or place

- Difficulty with visual and spatial relationships (beyond normal vision changes)

- Problems with words: speaking or writing

- Misplacing things and being unable to retrace steps

- Poor judgment

- Withdrawal from work or social activities

- Changes in mood or personality

The referral conversation:

"You mentioned you've been getting lost on familiar routes and your husband has noticed some changes. These things can have many causes, some very treatable. I think it would be worth talking to your doctor about it. Would you be willing to make an appointment?"

Important: Studies show that only about 26 percent of older adults who screen positive for cognitive issues accept referral for evaluation. Knowledge about cognitive impairment predicts acceptance. Your role in educating clients about the importance of evaluation and the treatability of many causes can help.

Integrating brain health into Deep Health coaching¶

Brain health isn't separate from overall health. It's deeply connected to every Deep Health dimension:

Physical: Exercise, sleep, nutrition, cardiovascular health all affect brain function

Mental/Cognitive: Direct focus on cognitive stimulation, learning, challenge

Emotional: Mood regulation, stress management, depression prevention

Social: Connection, relationships, community involvement

Existential: Purpose, meaning, engagement with life

Environmental: Air quality, noise, safety from head injury

When coaching for brain health, you're really coaching for Deep Health, with particular attention to the cognitive dimension. Everything interconnects.

Brain health without inducing anxiety¶

Some clients become anxious when discussing brain health, worrying about every forgotten name or missed appointment. Help these clients by:

-

Normalizing some forgetfulness: "Everyone forgets things sometimes. Occasional lapses are normal, especially when you're stressed or distracted."

-

Focusing on overall patterns: "Rather than worrying about individual incidents, we look at overall patterns over time."

-

Emphasizing the positive: "The fact that you're focused on brain health and taking action is itself protective. Stress and worry are more harmful than occasional forgetfulness."

-

Setting realistic expectations: "The goal isn't perfect memory, it's building a healthy foundation that supports your brain over time."

-

Redirecting rumination: "When you notice yourself worrying about your memory, try redirecting to one positive action you can take today."

| Coaching in practice | |

|---|---|

| Sample scripts for brain health conversations | |

| Client: "What should I be doing to prevent Alzheimer's?" | |

| Coach: "That's such an important question. First, I want to be honest. We can't guarantee prevention of any disease, including Alzheimer's. But research shows that lifestyle factors significantly influence brain health. The good news? The things that help your brain also help your entire body. Exercise, quality sleep, healthy eating, social connection, managing stress, and taking care of cardiovascular health: these are our focus areas. Which of these feels most manageable to start with?" | |

| Client: "Should I be taking supplements for my brain?" | |

| Coach: "Some supplements show modest benefits: omega-3s have the most evidence. But I'd put supplements in the 'nice-to-have, not need-to-have' category. The big wins come from foundational habits: exercise, sleep, diet, connection. Those are like the main course; supplements are more like seasoning. Let's make sure the main course is solid first." | |

| Client: "I forgot my neighbor's name and I'm worried something's wrong with me." | |

| Coach: "That's frustrating! But occasional word-finding difficulty is pretty common, especially when we're tired or stressed. What concerns me more is when people get lost in familiar places, can't follow conversations, or when others notice consistent changes. How has your overall cognitive function been? Any other changes you've noticed?" |

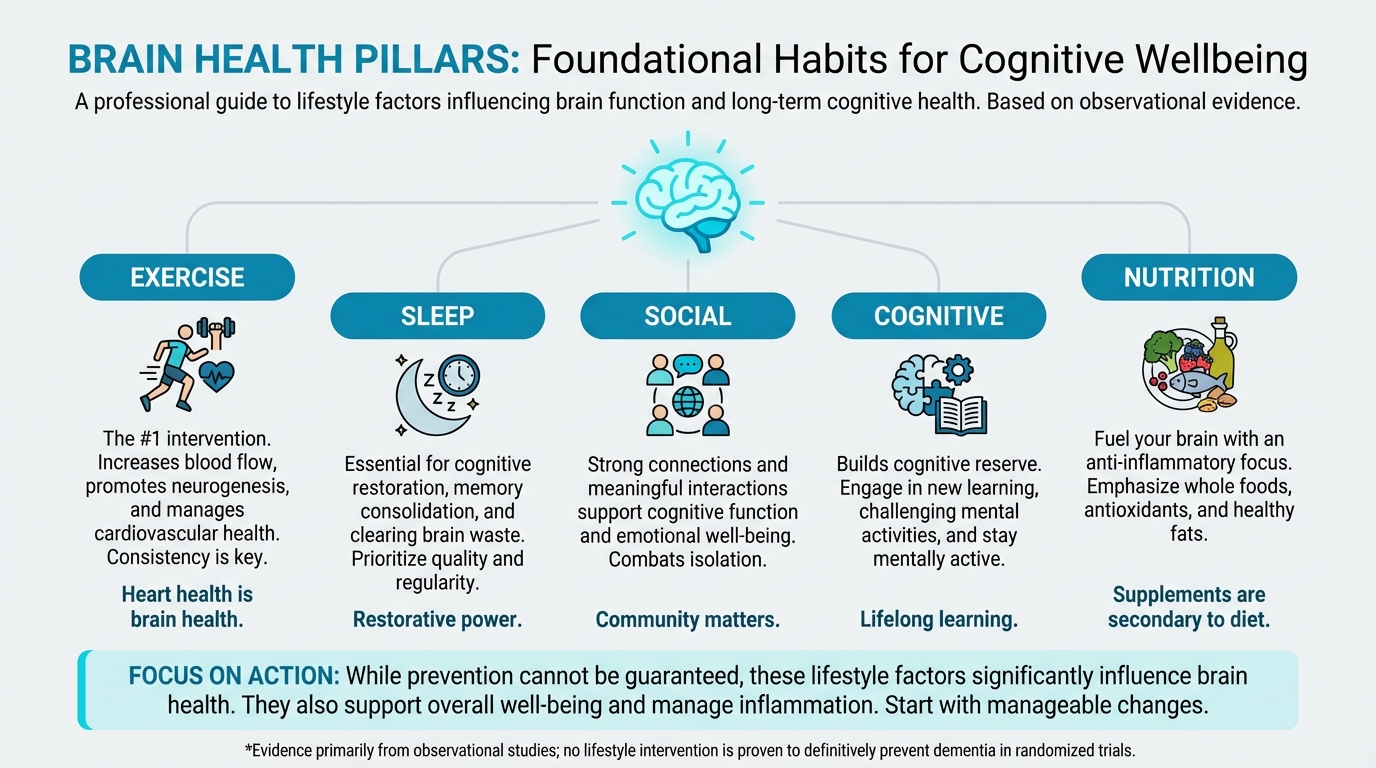

Figure: Exercise, sleep, social, cognitive, nutrition

[CHONK: Study guide questions]

Study guide questions¶

Here are some questions that can help you think through the material and prepare for the chapter exam. They're optional, but we recommend you try answering at least a few as part of your active learning process.

- What is cognitive reserve, and how is it built across the lifespan?

Figure: Building reserve across lifespan

-

According to the 2024 Lancet Commission, what percentage of dementia cases might be prevented or delayed by addressing modifiable risk factors? What caveats should you keep in mind about this number?

-

Why is exercise considered the #1 brain health intervention? What dose and type appear most beneficial?

-

How would you explain to a client why sleep matters for brain health, using accessible language?

-

What's the difference between what coaches can and cannot promise regarding brain health interventions?

-

List at least five of the 14 modifiable risk factors identified by the Lancet Commission. Which are cardiovascular-related?

-

When should you refer a client for medical evaluation of cognitive concerns? What warning signs would prompt referral?

-

How would you support a client with significant family history of dementia who is anxious about their own cognitive future?

Self-reflection questions:

-

Which of the 14 modifiable risk factors for dementia apply to you personally? Which one would you prioritize addressing first?

-

When did you last learn something genuinely new and challenging? Building cognitive reserve requires pushing beyond your comfort zone—not just doing crossword puzzles.

Chapter exam¶

Test your understanding of Chapter 3.18: Neuroprotection. Select the best answer for each question.

1. According to the 2024 Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, approximately what percentage of dementia cases might be prevented or delayed by addressing modifiable risk factors?

a) 15%

b) 25%

c) 45%

d) 75%

2. Which of the following is TRUE about the MIND diet?

a) Randomized trials consistently show it prevents dementia

b) Observational studies show consistent associations with better cognitive outcomes

c) It's identical to the Mediterranean diet

d) It has no scientific support

3. BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) is best described as:

a) A hormone that causes dementia

b) A protein that supports neuron survival and new connection formation

c) A type of brain scan

d) A medication for cognitive decline

4. Which lifestyle factor has the strongest evidence as a brain health intervention?

a) Supplement use

b) Brain training games

c) Physical exercise

d) Sauna use

5. A client mentions they sometimes forget where they put their keys. How should you respond?

a) Tell them this is an early sign of dementia

b) Reassure them that occasional forgetfulness is normal, but assess for other changes

c) Recommend they see a neurologist immediately

d) Ignore the concern

6. The glymphatic system is:

a) A type of brain training

b) The brain's waste clearance system, most active during sleep

c) A supplement for brain health

d) A genetic marker for Alzheimer's

7. Which TWO risk factors were newly added in the 2024 Lancet Commission update?

a) Depression and anxiety

b) High LDL cholesterol and untreated vision loss

c) Smoking and alcohol

d) Obesity and diabetes

8. A coach's appropriate role in brain health includes all EXCEPT:

a) Providing evidence-based education about lifestyle factors

b) Supporting behavior change for modifiable risk factors

c) Diagnosing cognitive impairment

d) Recognizing when to refer to medical professionals

9. What does cognitive reserve refer to?

a) How much memory capacity remains after dementia

b) The brain's ability to compensate and find alternate pathways when facing damage

c) A type of brain supplement

d) The number of neurons you're born with

10. Social isolation increases dementia risk through which mechanisms?

a) Reduced cognitive stimulation

b) Increased stress and inflammation

c) Lower BDNF levels

d) All of the above

11. When a client expresses fear about dementia because their parent had Alzheimer's, the BEST response is:

a) "You won't get it if you exercise enough"

b) "Don't worry about it. There's nothing you can do"

c) Acknowledge the fear, provide context about genetics and lifestyle, and focus on actionable steps

d) Recommend genetic testing immediately

12. The evidence for sauna use and dementia risk reduction is best characterized as:

a) Strong: multiple randomized trials prove it prevents dementia

b) Preliminary: observational data from Finnish cohorts, causality not established

c) Non-existent: no studies have examined this

d) Moderate: several RCTs show significant effects

13. Which statement about brain games and cognitive training is accurate?

a) They reliably prevent dementia

b) They improve performance on trained tasks but show limited transfer to real-world function

c) They're more effective than physical exercise for brain health

d) The FTC endorses them for dementia prevention

14. Warning signs that should prompt referral for cognitive evaluation include all EXCEPT:

a) Getting lost in familiar places

b) Occasionally forgetting a word

c) Personality changes noticed by others

d) Difficulty following conversations

15. The phrase "we optimize, we don't guarantee" means:

a) Coaches can promise dementia prevention if clients follow the program

b) We can focus on modifiable factors while acknowledging we can't promise specific outcomes

c) Brain health interventions don't work

d) Only doctors can discuss brain health

Works cited¶

References¶

-

Livingston G, Huntley J, Liu KY, Costafreda SG, Selbæk G, Alladi S, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. The Lancet. 2024;404(10452):572-628. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(24)01296-0

-

Desai R, John A, Saunders R, Marchant NL, Buckman JEJ, Charlesworth G, et al. Examining the Lancet Commission risk factors for dementia using Mendelian randomisation. BMJ Mental Health. 2023;26(1):e300555. doi:10.1136/bmjment-2022-300555

-

Singh B, Bennett H, Miatke A, Dumuid D, Curtis R, Ferguson T, et al. Effectiveness of exercise for improving cognition, memory and executive function: a systematic umbrella review and meta-meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2025;59(12):866-876. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2024-108589

-

Zhang M, Fang W, Wang J. Effects of human concurrent aerobic and resistance training on cognitive health: A systematic review with meta-analysis. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2025;25(1):100559. doi:10.1016/j.ijchp.2025.100559

-

Liu H, Sun Z, Zeng H, Han J, Hu M, Mao D, et al. Meta-analysis of the effects of multi-component exercise on cognitive function in older adults with cognitive impairment. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2025;17. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2025.1551877

-

Wang Y, Li F, Cao S, Jia J. Dose- and pattern- physical activity is associated with lower risk of dementia. The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer's Disease. 2025;12(7):100223. doi:10.1016/j.tjpad.2025.100223

-

Hu M, Zhang K, Su K, Qin T, Shen H, Deng H. Unveiling the link between physical activity levels and dementia risk: Insights from the UK Biobank study. Psychiatry Research. 2024;336:115875. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2024.115875

-

Barnes LL, Dhana K, Liu X, Carey VJ, Ventrelle J, Johnson K, et al. Trial of the MIND Diet for Prevention of Cognitive Decline in Older Persons. New England Journal of Medicine. 2023;389(7):602-611. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2302368

-

Chen H, Dhana K, Huang Y, Huang L, Tao Y, Liu X, et al. Association of the Mediterranean Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) Diet With the Risk of Dementia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80(6):630. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.0800

-

Barros MI, Brandão T, Irving SC, Alves P, Gomes F, Correia M. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Cognitive Decline in Adults with Non-Dementia or Mild Cognitive Impairment: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Nutrients. 2025;17(18):3002. doi:10.3390/nu17183002

-

Suh SW, Lim E, Burm S, Lee H, Bae JB, Han JW, et al. The influence of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on cognitive function in individuals without dementia: a systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis. BMC Medicine. 2024;22(1). doi:10.1186/s12916-024-03296-0

-

Luchetti M, Aschwanden D, Sesker AA, Zhu X, O’Súilleabháin PS, Stephan Y, et al. A meta-analysis of loneliness and risk of dementia using longitudinal data from >600,000 individuals. Nature Mental Health. 2024;2(11):1350-1361. doi:10.1038/s44220-024-00328-9

-

Huang AR, Roth DL, Cidav T, Chung S, Amjad H, Thorpe RJ, et al. Social isolation and 9‐year dementia risk in

<scp>community‐dwelling</scp>

Medicare beneficiaries in the United States. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2023;71(3):765-773. doi:10.1111/jgs.18140 -

Sutin AR, Luchetti M, Stephan Y, Terracciano A. Purpose in life and cognitive health: a 28-year prospective study. International Psychogeriatrics. 2024;36(10):956-964. doi:10.1017/s1041610224000383

-

Buchman AS. Effect of Purpose in Life on the Relation Between Alzheimer Disease Pathologic Changes on Cognitive Function in Advanced Age. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(5):499. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1487

-

Zhou B, Wang Z, Zhu L, Huang G, Li B, Chen C, et al. Effects of different physical activities on brain-derived neurotrophic factor: A systematic review and bayesian network meta-analysis. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2022;14. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2022.981002

-

Resende-Silva S, de Resende-Neto AG, Vasconcelos ABS, Pereira-Monteiro MR, Pantoja-Cardoso A, Santana Santos LE, et al. Functional training improves cognitive function, functional fitness, and BDNF levels in older women with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Physiology. 2025;16. doi:10.3389/fphys.2025.1638590

-

Xu C, Bi S, Zhang W, Luo L. The effects of creatine supplementation on cognitive function in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2024;11. doi:10.3389/fnut.2024.1424972

-

Sandkühler JF, Kersting X, Faust A, Königs EK, Altman G, Ettinger U, et al. The effects of creatine supplementation on cognitive performance - a randomised controlled study. 2023. doi:10.1101/2023.04.05.23288194

-

EFSA NDA Panel. Evaluation of health claims related to creatine and cognitive function. EFSA Journal; 2024. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11574456/

-

Syed M, Lum JAG, Byrne LK, Skvarc D. Examining Working Memory Training for Healthy Adults—A Second-Order Meta-Analysis. Journal of Intelligence. 2024;12(11):114. doi:10.3390/jintelligence12110114

-

Hampshire A, Sandrone S, Hellyer PJ. A Large-Scale, Cross-Sectional Investigation Into the Efficacy of Brain Training. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2019;13. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2019.00221

-

Schwartz HE, Bay CP, McFeeley BM, Krivanek TJ, Daffner KR, Gale SA. The Brain Health Champion study: Health coaching changes behaviors in patients with cognitive impairment. Alzheimer's & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. 2019;5(1):771-779. doi:10.1016/j.trci.2019.09.008

-

Laukkanen T, Kunutsor S, Kauhanen J, Laukkanen JA. Sauna bathing is inversely associated with dementia and Alzheimer's disease in middle-aged Finnish men. Age and Ageing. 2016;46(2):245-249. doi:10.1093/ageing/afw212

-

Knekt P, Järvinen R, Rissanen H, Heliövaara M, Aromaa A. Does sauna bathing protect against dementia?. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2020;20:101221. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101221

-

Wei BZ, et al.. The Relationship of Omega-3 Fatty Acids with Dementia and Cognitive Decline: Evidence from Prospective Cohort Studies and Meta-Analyses. Am J Clin Nutr; 2023. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10447496/

-

Harrington KD, Vasan S, Kang Je, Sliwinski MJ, Lim MH. Loneliness and Cognitive Function in Older Adults Without Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2023;91(4):1243-1259. doi:10.3233/jad-220832

-

Salinas J, Beiser A, Himali JJ, Satizabal CL, Aparicio HJ, Weinstein G, et al. Associations between social relationship measures, serum brain‐derived neurotrophic factor, and risk of stroke and dementia. Alzheimer's & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. 2017;3(2):229-237. doi:10.1016/j.trci.2017.03.001

-

Iso-Markku P, Aaltonen S, Kujala UM, Halme H, Phipps D, Knittle K, et al. Physical Activity and Cognitive Decline Among Older Adults. JAMA Network Open. 2024;7(2):e2354285. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.54285

-

Baker LD, Espeland MA, Whitmer RA, Snyder HM, Leng X, Lovato L, et al. Structured vs Self-Guided Multidomain Lifestyle Interventions for Global Cognitive Function. JAMA. 2025;334(8):681. doi:10.1001/jama.2025.12923

-

Deng C, Shen N, Li G, Zhang K, Yang S. Digital Isolation and Dementia Risk in Older Adults: Longitudinal Cohort Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2025;27:e65379. doi:10.2196/65379

Answer Key:

1. c

2. b

3. b

4. c

5. b

6. b

7. b

8. c

9. b

10. d

11. c

12. b

13. b

14. b

15. b