Unit 3: Advanced Topics & Disease Prevention¶

Chapter 3.16: Cardiovascular Health¶

[CHONK: 1-minute summary]

The big idea¶

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the #1 killer worldwide, responsible for about one in three deaths globally. That's approximately 20 million deaths per year, more than all cancers combined. The sobering truth: most people you coach will have cardiovascular disease as a significant factor in their eventual mortality.

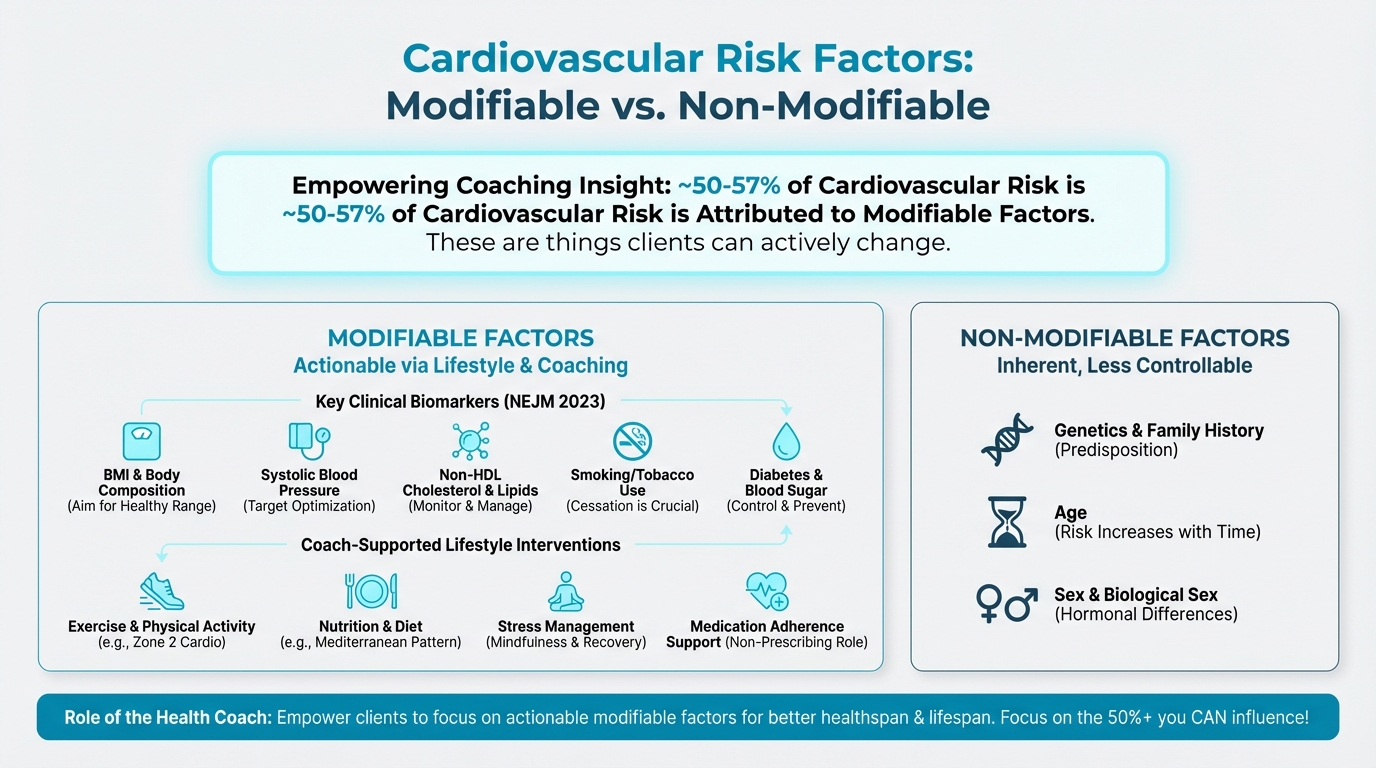

But here's the hopeful part: CVD is remarkably preventable. About 50-57% of cardiovascular events can be attributed to modifiable risk factors, meaning things your clients can actually change. The lifestyle interventions you'll support as a coach (exercise, nutrition, stress management, blood pressure optimization) are among the most powerful tools available for extending healthspan and lifespan.

Figure: Modifiable vs non-modifiable factors

This chapter covers what coaches need to know about cardiovascular health: how atherosclerosis develops, what cardiac biomarkers measure (without interpreting them medically), evidence-based lifestyle interventions, and clear boundaries for when to refer clients to cardiologists. Throughout, we'll be precise about scope. You educate and support, you don't diagnose or prescribe.

Key takeaways:

- CVD causes ~1 in 3 deaths globally (~20 million per year)

- 50-57% of CVD risk is attributed to modifiable factors

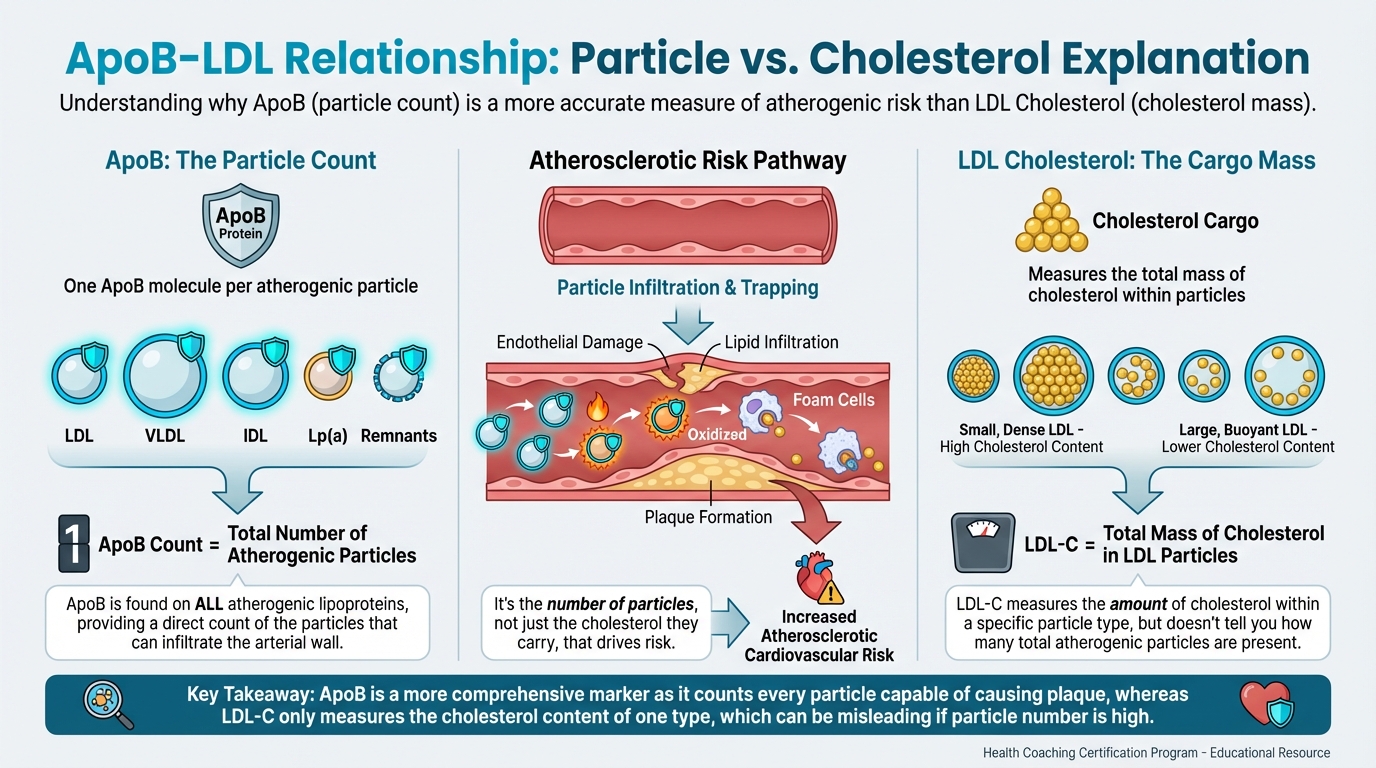

- ApoB is emerging as the key biomarker (better than LDL alone)

- Zone 2 cardio, Mediterranean diet, and blood pressure control are foundational

- Coaches explain what biomarkers measure, not what the numbers mean medically

- Clear referral criteria protect both you and your clients

[CHONK: Section 1 - Understanding the #1 Killer]

Understanding the #1 killer¶

The global burden of cardiovascular disease¶

Let's start with the numbers, because they're staggering. According to WHO and Global Burden of Disease analyses, cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for approximately 30-33% of all global deaths.[^1]

To put this in concrete terms:

- ~20 million deaths per year from CVD (2021-2023 estimates)

- 1 in 3 deaths globally is due to cardiovascular disease

- 80% of CVD deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries

- 85% of CVD deaths are due to heart attack and stroke

- About one-third of CVD deaths occur before age 70

These aren't abstract statistics; they represent the leading threat to your clients' lives and longevity. That means understanding cardiovascular disease isn't optional for a longevity coach; it's foundational.

How atherosclerosis develops¶

This is what's actually happening inside blood vessels when cardiovascular disease develops. This isn't medical detail you need to memorize, but understanding the basic process helps you explain why lifestyle interventions matter.

Atherosclerosis is the underlying disease process behind most heart attacks and strokes. The name comes from Greek: athere (gruel/porridge) + sclerosis (hardening), describing the fatty, hardened deposits that form in arteries.

The process, simplified:

Step 1: The initial injury. Atherosclerosis begins with damage to the endothelium, the thin layer of cells lining your arteries. High blood pressure, smoking, high blood sugar, and chronic inflammation all damage this protective layer. Once damaged, the endothelium becomes "leaky," allowing particles to enter the arterial wall.[^2]

Step 2: Lipid infiltration. When the endothelial barrier is damaged, cholesterol-carrying particles, especially LDL and other apoB-containing lipoproteins, can infiltrate and get trapped in the arterial wall. These particles become oxidized (chemically modified), which triggers an immune response.[^3]

Figure: Particle vs cholesterol explanation

Step 3: Inflammation and foam cells. Your immune system sends white blood cells (monocytes) to clean up the oxidized particles. These cells become "foam cells", bloated with cholesterol. This creates a fatty streak, the earliest visible sign of atherosclerosis. This process can begin as early as childhood.[^4]

Step 4: Plaque formation. Over time, smooth muscle cells migrate into the area and produce fibrous tissue, forming a cap over the fatty core. The plaque grows, narrowing the artery and restricting blood flow. This process takes decades. Atherosclerosis is a life-course disease.[^5]

Step 5: The dangerous event. Not all plaques are created equal. Some develop a thin cap with lots of inflammatory cells. These "vulnerable" plaques are prone to rupture. When a plaque ruptures, it triggers blood clot formation (thrombosis). If this happens in a coronary artery, you get a heart attack. In an artery supplying the brain, you get a stroke.[^6]

The key insight for coaches: This isn't something that happens overnight. Atherosclerosis develops over decades, driven by cumulative exposure to risk factors. Every day your client makes healthier choices, they're slowing or potentially reversing this process. Every day of unhealthy choices accelerates it.

Why this matters for coaching¶

Understanding atherosclerosis helps you explain why the interventions work:

- Lower ApoB/LDL → fewer particles infiltrating arteries

- Lower blood pressure → less endothelial damage

- Better blood sugar control → less endothelial damage

- Less inflammation → slower progression and more stable plaques

- Smoking cessation → endothelium can begin to heal

When clients understand the mechanism, they're more motivated to sustain changes. "Eat less saturated fat because it's bad" is less compelling than "This intervention reduces the particles that drive the plaque-building process."

The good news: Highly modifiable¶

Here's what makes cardiovascular disease different from many other leading causes of death: it's remarkably preventable.

A landmark 2023 analysis in the New England Journal of Medicine pooled data from global cohorts and found that five modifiable factors, BMI, systolic blood pressure, non-HDL cholesterol, smoking, and diabetes, explain approximately 53-57% of 10-year incident CVD and about 19-22% of 10-year all-cause mortality.[^7]

Let that sink in. More than half of cardiovascular events could theoretically be prevented by addressing factors your clients can modify.

Additional evidence for prevention:

- Lifestyle interventions (diet and/or physical activity) significantly reduce estimated 10-year CVD risk in adults without CVD[^8]

- Among patients with established CVD, each additional healthy lifestyle behavior is associated with ~17% lower risk of adverse outcomes[^9]

- Smoking cessation after a heart attack reduces mortality by about 37% (HR ~0.63)[^10]

This is why cardiovascular health deserves a dedicated chapter. The opportunity to impact your clients' lives is enormous.

Coaching in practice: Discussing CVD risk without causing alarm¶

The scenario: You're introducing cardiovascular health, and a client looks worried when you mention that heart disease is the number one killer.

What NOT to do:

❌ Launch into a long list of statistics and family history questions without checking in on how they feel.

Why it doesn't work: It can increase anxiety and make the risk feel overwhelming and inevitable.

What TO do:

✅ Acknowledge the seriousness, then pivot to what they can influence.

Sample dialogue:

Client: "Wow, heart disease is the number one killer? That really freaks me out."

Coach: "It is serious, and that's why we pay attention to it. The encouraging part is that more than half of that risk comes from things we can actually change together—like movement, nutrition, blood pressure, and smoking."

Client: "So it's not just about genes?"

Coach: "Exactly. Unlike some conditions where genetics dominate, heart disease is largely about lifestyle choices accumulated over time. Every healthy choice you make is literally slowing down a process that takes decades to develop."

Client: "That makes me feel a bit better. It sounds like I have some control."

Coach: "You do. You're not fighting fate; you're stacking the odds in your favor, one decision at a time. Instead of worrying about the statistics, let's pick one or two things you can start working on this week."

Key takeaway: Name the risk honestly, but quickly shift the focus to actionable steps and the client's ability to influence their trajectory.

[CHONK: Section 2 - Cardiac Biomarkers: What Coaches Should Know]

Cardiac biomarkers: What coaches should know¶

Scope reminder: What you can and can't do¶

Before diving into biomarkers, let's be explicit about boundaries. This matters for your professional protection and your clients' safety.

What coaches CAN do:

- Explain what biomarkers measure (educational)

- Describe general ranges and what they indicate (without interpreting specific numbers)

- Encourage clients to discuss results with their physician

- Support clients in understanding their doctor's recommendations

- Track whether clients are following up on recommended testing

What coaches CANNOT do:

- Interpret specific test results ("Your LDL of 145 is concerning")

- Diagnose cardiovascular conditions

- Recommend for or against medications

- Advise on medication dosages or timing

- Tell clients their numbers are "fine" or "problematic"

The phrase to remember: "That's a great question for your doctor. What I can tell you is what this test measures and why doctors find it useful."

As discussed in Chapter 1.5 (Scope of Practice), staying within these boundaries protects your clients from potential harm and protects you professionally.

ApoB: The particle that matters¶

If you remember one biomarker from this chapter, make it apolipoprotein B (ApoB). It's increasingly recognized as the most accurate measure of atherogenic (plaque-building) risk.

What ApoB measures:

ApoB is a protein found on the surface of all atherogenic lipoproteins, the particles that can infiltrate arterial walls and drive atherosclerosis. These include LDL particles, VLDL particles, and others. Each of these particles has exactly one ApoB molecule on it.

So when you measure ApoB, you're essentially counting the total number of atherogenic particles in the blood. This is clinically important because it's the number of particles, not just the cholesterol they carry, that drives risk.[^11]

Why ApoB is better than LDL-C:

Traditional LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) measures the amount of cholesterol carried in LDL particles. But here's the problem: LDL particles vary in size. Some people have fewer, larger LDL particles; others have more, smaller particles. Two people with identical LDL-C could have very different particle counts, and very different risks.

Research consistently shows that when LDL-C and ApoB disagree (discordance), cardiovascular risk aligns better with ApoB.[^12] In the UK Biobank cohort of nearly 300,000 people followed for ~11 years, participants with the same LDL-C (~130 mg/dL) had very different outcomes depending on their ApoB levels. Ten-year ASCVD rates were 7.3% vs 4.0% for those above vs below mean ApoB.[^13]

A 2024 expert consensus from the National Lipid Association recommends routine ApoB measurement and proposes treatment thresholds:[^14]

- <60 mg/dL for very high risk

- <70 mg/dL for high risk

- <90 mg/dL for borderline/intermediate risk

If all of these cutoffs feel like a lot to remember, that's okay. As a coach, you just need the big picture: in general, lower ApoB means lower long-term risk, and clinicians use these numbers to decide when medication or more intensive treatment makes sense.

What this means for coaches:

You don't interpret ApoB numbers. But you can explain:

"ApoB counts the number of potentially harmful particles in your blood. Doctors are increasingly using it because it may be more accurate than traditional cholesterol tests. If your doctor has checked your ApoB, that's a sign they're being thorough. Ask them what it means for your situation."

The traditional lipid panel¶

Most clients will have a standard lipid panel rather than ApoB testing. Here's what these tests measure, again, educationally, not interpretively.

Total cholesterol: The sum of all cholesterol in the blood. Limited usefulness because it combines "good" and "bad" cholesterol.

LDL cholesterol (LDL-C): Cholesterol carried in LDL particles, traditionally called "bad cholesterol" because LDL particles contribute to plaque formation. Higher LDL-C generally indicates higher risk.

HDL cholesterol (HDL-C): Cholesterol carried in HDL particles, traditionally called "good cholesterol" because HDL is involved in removing cholesterol from tissues. Higher HDL-C has historically been associated with lower risk, though raising HDL with drugs hasn't proven beneficial.

Triglycerides: Fats in the blood. High levels are associated with cardiovascular risk, especially when combined with low HDL and high LDL.

Non-HDL cholesterol: Total cholesterol minus HDL cholesterol. This captures all atherogenic particles, not just LDL. Many guidelines now emphasize non-HDL-C as a secondary target because it correlates well with ApoB.[^15]

What coaches should know about interpretation:

Labs automatically report ranges (often "normal," "borderline," "high"). However, there is important nuance: optimal ranges vary by individual risk. Someone with diabetes, prior heart disease, or multiple risk factors may need lower numbers than someone with no risk factors.

This is why interpretation belongs with physicians. Your role: "I see your doctor ordered a lipid panel. Once you get the results and discuss them with your doctor, I'd love to hear what they recommend and how I can support those goals."

Blood pressure basics¶

Blood pressure is the other critical cardiovascular marker. Unlike lipids (which require a lab), blood pressure can be measured easily and frequently.

What the numbers mean:

Blood pressure is expressed as two numbers:

- Systolic (top number): Pressure during heart contraction

- Diastolic (bottom number): Pressure between beats

General categories (per 2025 guidelines):[^16]

- Normal: <120/<80 mmHg

- Elevated: 120-139/70-89 mmHg (new ESC 2024 category)

- Stage 1 hypertension: 130-139/80-89 mmHg (US) or treated SBP 120-129 (ESC goal)

- Stage 2 hypertension: ≥140/≥90 mmHg

- Hypertensive crisis: ≥180/≥120 mmHg (requires immediate medical attention)

Why blood pressure matters:

High blood pressure damages the endothelium (the arterial lining), accelerating atherosclerosis. It also increases the workload on the heart and damages other organs over time. Blood pressure control is one of the most impactful interventions for cardiovascular prevention.

Current guidelines (AHA/ACC 2025) recommend a universal treatment goal of <130/80 mmHg for adults.[^17] The ESC 2024 guideline recommends a treated SBP target range of 120-129 mmHg for most patients.[^18]

What coaches can do:

- Encourage regular blood pressure monitoring (home BP monitors are affordable and recommended)

- Support clients in tracking and sharing readings with their healthcare team

- Discuss lifestyle factors that influence blood pressure (covered in Section 3)

- Recognize warning signs that require immediate referral (covered in Section 5)

Scope-safe language: "Blood pressure is one of the most important numbers for heart health. I'm glad your doctor is monitoring it. If you want to track it at home between visits, that can give your doctor really useful information."

Understanding cardiovascular risk calculators¶

Your clients may mention that their doctor discussed "10-year heart disease risk" or used a "risk calculator." This is what they're talking about, not so you can use these tools yourself, but so you can help clients understand them.

What risk calculators do:

These tools combine multiple risk factors (age, blood pressure, cholesterol, smoking status, diabetes, etc.) to estimate someone's probability of having a heart attack or stroke over the next 10 years. Common ones include:

- Pooled Cohort Equations (PCE/ASCVD) - used in the US

- QRISK3 - used in the UK

- SCORE2 - used in Europe

Why they matter:

Risk calculators help doctors decide who benefits most from interventions like statins. Someone with "borderline" cholesterol but multiple other risk factors might have higher overall risk than someone with "high" cholesterol but no other factors.

What coaches should know:

These calculators have limitations. They can overestimate risk in some populations and underestimate in others. They're guides, not oracles. One analysis found that legacy calculators often overpredict risk by 2-3x in contemporary populations.[^19]

New models (like PREVENT) are being developed to improve accuracy, though they're not yet universally adopted.[^20]

If all of this talk about risk equations and recalibration feels abstract, that's normal. For coaching, the key idea is that these tools give doctors a rough estimate of a person's chances of having a cardiovascular event, and your role is to support whatever treatment and lifestyle plan the medical team recommends—not to debate the exact percentage.

Scope-safe framing: "Risk calculators combine multiple factors to estimate your overall heart disease probability. They help doctors make treatment decisions. If your doctor mentioned your 10-year risk, that's a useful number to know. What matters more is the plan you and your doctor develop together to improve that trajectory."

Lipoprotein(a): The genetic wild card¶

Some of your clients may mention Lp(a), pronounced "L-P-little-a." This is a genetically determined lipoprotein that independently increases cardiovascular risk.

What coaches should know:

- Lp(a) levels are ~80-90% determined by genetics

- High Lp(a) increases cardiovascular risk independent of LDL

- Many guidelines now recommend measuring Lp(a) once in a lifetime for risk stratification[^21]

- There's currently no approved medication specifically targeting Lp(a), though several are in development

- Lifestyle has minimal impact on Lp(a) (unlike LDL, which responds to diet and exercise)

Why this matters for coaching:

If a client has high Lp(a), they may need more aggressive management of other risk factors to compensate. This is a conversation for their doctor. Your role: support whatever plan the medical team recommends.

"Lp(a) is mostly genetic. It's not something you caused or can change much with lifestyle. But knowing about it helps your doctor understand your total risk picture and tailor recommendations accordingly."

Coaching in practice: When clients ask you to interpret their labs¶

The scenario: A client shares their lipid panel (and maybe an ApoB level) and says, "What do you think?"

What NOT to do:

❌ Start interpreting the numbers or suggesting changes to medications or supplements.

Why it doesn't work: Interpretation and treatment decisions belong to the prescribing clinician, and stepping into that role can be unsafe for the client and outside your scope.

What TO do:

✅ Appreciate their trust, explain what the tests measure in plain language, and direct detailed interpretation back to their doctor.

Sample dialogue:

Client: "My labs came back and my LDL and ApoB are highlighted in red. What do you think?"

Coach: "I really appreciate you trusting me with this. Interpreting specific lab results is your doctor's job, but I can definitely help you understand what these tests measure."

Client: "Okay, so what are they looking at?"

Coach: "LDL tells your doctor how much cholesterol is being carried in certain particles, and ApoB counts how many of those potentially harmful particles are in your blood. Many doctors like ApoB because particle number can give a clearer picture of risk. The most important thing is what your doctor says these results mean for you personally."

Client: "I'm a bit worried about the red numbers."

Coach: "I hear that. The best next step is a detailed conversation with your doctor about what the results mean for your situation and what options you have. If you like, we can brainstorm questions you might ask at your appointment, and then I can support you in following whatever plan you and your doctor decide on."

Key takeaway: Stay out of interpreting specific lab values, but be generous with education and support so clients feel informed and prepared for conversations with their healthcare team.

[CHONK: Section 3 - Lifestyle Interventions for Heart Health]

Lifestyle interventions for heart health¶

Zone 2 cardio: The cardiovascular intervention¶

As covered extensively in Chapter 2.9 (Exercise: The Longevity Drug), Zone 2 cardio is foundational for cardiovascular health. Here's the cardiovascular-specific evidence.

What Zone 2 does for the heart:

Zone 2 training (moderate-intensity aerobic exercise at or below the first ventilatory threshold) provides cardiovascular benefits through multiple mechanisms:[^22]

- Increases mitochondrial content and efficiency in heart and skeletal muscle

- Improves cardiac energy production through more efficient mitochondrial function

- Reduces oxidative stress in cardiovascular tissues

- Promotes vascular remodeling (angiogenesis, arteriogenesis)

- Improves oxygen delivery and extraction

- Lowers resting blood pressure

The dose-response:

Major meta-analyses show clear cardiovascular benefits from moderate-intensity activity:[^23]

- Per +20 MET-hours/week of leisure-time physical activity: ~10% lower CVD, 12% lower CHD, 9% lower stroke, 8% lower atrial fibrillation risk

- At guideline levels (~150 min/week moderate activity): all-cause mortality RR 0.69, CVD mortality RR 0.71

- Most benefit occurs in the transition from inactive to meeting basic guidelines

- Additional benefits continue up to ~20-25 MET-hours/week, then plateau

Blood pressure effects:

Regular aerobic exercise produces meaningful blood pressure reductions:[^24]

- In hypertensive adults: ~8-14 mmHg systolic, ~5-8 mmHg diastolic reduction

- In metabolic syndrome: ~5/3 mmHg reduction

- In resistant hypertension: ~12/8 mmHg reduction (even when medications aren't fully working)

These effects are comparable to adding a blood pressure medication.

What coaches should know:

The longevity protocol recommends 150-300 minutes per week of Zone 2 cardio. This aligns with guidelines from WHO, AHA, and other major organizations. Your role is helping clients find sustainable ways to achieve this volume. You are not prescribing specific exercise programs.

Mediterranean diet and fiber¶

The Mediterranean diet evidence:

The Mediterranean diet has the strongest evidence base of any dietary pattern for cardiovascular protection. Multiple meta-analyses confirm its benefits:[^25]

- MACE reduction: ~48% lower odds (OR ~0.52) vs control diets

- Stroke: ~40% lower risk (HR ~0.60)

- Myocardial infarction: ~38% lower odds

- Cardiovascular death: ~46% lower odds

Notably, effects on all-cause mortality are less consistent. Some analyses show reduction, others don't reach statistical significance. But for cardiovascular-specific outcomes, the evidence is strong.

What makes it work:

The Mediterranean diet is characterized by:

- High intake of vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, whole grains

- Olive oil as the primary fat source

- Moderate fish and poultry

- Low red meat and processed meat

- Moderate wine with meals (optional)

- Limited sweets and processed foods

The cardiovascular benefits likely come from multiple components: high fiber, polyphenols from olive oil, omega-3s from fish, lower saturated fat, and the overall dietary pattern.

Fiber: The underappreciated intervention:

Fiber deserves special attention for cardiovascular health. The evidence is strong:[^26]

- LDL reduction: Soluble fiber supplementation reduces LDL-C by ~8 mg/dL and total cholesterol by ~11 mg/dL

- Dose-response: Each +5 g/day of soluble fiber reduces LDL-C by ~5.6 mg/dL and total cholesterol by ~6.1 mg/dL

- Stroke risk: High fiber intake (~18+ g/day) associated with 29% lower stroke odds

- Mortality: High vs low fiber intake associated with ~25% lower all-cause mortality in people with CVD/hypertension

The longevity protocol recommends 35-50g of fiber daily. Most Americans get about 15g. This is low-hanging fruit for cardiovascular improvement.

How fiber works:

Soluble fiber (found in oats, beans, apples, and psyllium) binds bile acids in the intestine. Your liver then pulls cholesterol from the blood to make more bile acids, effectively lowering circulating cholesterol. It's a simple, well-established mechanism.

Blood pressure lifestyle interventions¶

Blood pressure is highly responsive to lifestyle changes. Here's what the research shows:[^27]

Sodium reduction:

- Reducing sodium intake lowers SBP by ~4-8 mmHg on average

- After just one week, a low-sodium diet reduced SBP by ~8 mmHg vs high-sodium, ~6 mmHg vs usual diet

- Dose-response: each ~1,150 mg reduction in sodium = ~1.1 mmHg SBP reduction

- Target: <2,000 mg/day sodium (about 1 teaspoon of salt)

Potassium increase:

- Potassium supplementation reduces SBP by ~4 mmHg, DBP by ~2.5 mmHg

- Salt substitutes (replacing sodium with potassium) reduced stroke by 14%, major CVD events by 13%, and death by 12% in a large trial[^28]

- Target: ≥3,500 mg/day potassium, preferably from food sources

DASH diet:

- DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) reduces BP by ~3-5 mmHg SBP and ~2-3 mmHg DBP

- Combined low-sodium DASH produces larger effects (~7+ mmHg)

- Also reduces estimated 10-year CVD risk by ~9-14%

Weight loss:

- Approximately 1 mmHg SBP reduction per kg of weight loss

- A 10 kg (22 lb) weight loss could reduce SBP by ~10 mmHg

Alcohol reduction:

- In heavier drinkers (>2 drinks/day), cutting intake by ~50% lowers BP by ~5.5/4.0 mmHg

Exercise:

- Covered above; ~4-14 mmHg reductions depending on baseline and modality

- Isometric training (like wall sits and handgrip exercises) shows particularly strong effects (~7-8 mmHg SBP)

The additive effect:

These interventions stack. A client who reduces sodium, increases potassium, loses weight, exercises regularly, and moderates alcohol could see 15-25+ mmHg improvement in systolic blood pressure, potentially eliminating the need for medication or reducing medication burden.

Saturated fat: A careful conversation¶

The saturated fat question deserves careful treatment because there's genuine scientific debate. Here's how to discuss it accurately.

What the evidence shows:

For the mainstream view (reduce saturated fat):

- Reducing saturated fat for ≥2 years probably lowers combined CVD events by ~14-21%[^29]

- Replacing saturated fat with polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs) shows the strongest benefit

- Replacing 5% of energy from saturated fat with PUFA, MUFA, or whole-grain carbs lowers CHD risk by 25%, 15%, and 9% respectively[^30]

- Saturated fat tends to raise LDL-C and ApoB compared to unsaturated fats

- WHO and AHA recommend limiting saturated fat to <10% of calories

For a more detailed view:

- RCT-only meta-analyses show no significant effect on cardiovascular or all-cause mortality

- Effects vary by what replaces saturated fat (refined carbs don't help)

- Saturated fat subtypes differ: even-chain SFAs associate with higher risk, odd-chain (from dairy) associate with lower risk

- Food matrix matters: cheese is less LDL-raising than butter at equal saturated fat content

- Some individuals are "hyper-responders" to dietary fat, others are not

What this means for coaches:

The scientific consensus still favors reducing saturated fat, especially when replacing it with unsaturated fats (olive oil, nuts, fish) or high-fiber carbohydrates, not refined carbs or sugar.

But blanket statements like "saturated fat causes heart disease" oversimplify the science. The key message:

The research suggests that replacing saturated fat-rich foods like butter with plant oils or nuts is associated with lower cardiovascular risk. But it matters what you replace it with. Swapping butter for white bread doesn't help. And individual responses vary. If your ApoB or LDL is elevated, your doctor may specifically recommend reducing saturated fat.

If this all feels a bit confusing or even contradictory, you're not alone; many health professionals wrestle with this topic too. From a coaching standpoint, you can keep it simple: emphasize plenty of plants, whole foods, and mostly unsaturated fats, then adjust saturated fat based on your client's lab markers and their doctor's guidance.

For clients whose ApoB is elevated (per the protocol), minimizing saturated fat makes sense. For clients with normal markers, moderate saturated fat in the context of an otherwise healthy diet is probably fine.

Stress management and heart health¶

Chronic stress is a major, often overlooked, cardiovascular risk factor. The evidence is substantial:[^31]

Epidemiological evidence:

- High stress vs no stress associated with ~24% higher CHD risk and ~30% higher stroke risk (PURE study, 21 countries)

- Chronic stress independently predicts hard CVD events even after adjusting for traditional risk factors

Biological mechanisms:

- Elevated cortisol and norepinephrine associated with ~60-70% higher CVD risk

- Dysregulated diurnal cortisol patterns predict CVD mortality (higher late-night cortisol: HR ~1.49)

- Chronic stress activates inflammatory pathways (elevated IL-6, CRP, etc.)

- Acute mental stress can trigger myocardial ischemia in ~16% of people with coronary artery disease. This "mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia" carries a ~2.5x higher risk of CV death or heart attack

The brain-heart connection:

Brain imaging studies have shown that elevated activity in the amygdala, the brain's fear and stress processing center, predicts bone marrow activation, arterial inflammation, and future CVD events. Stress literally drives the inflammatory processes that build plaque.[^32]

What helps:

Stress-reduction interventions show cardiovascular benefits:[^33]

- Stress management produces short-term SBP reductions of ~6-10 mmHg

- Stress-reducing interventions improve heart rate variability (a marker of cardiac health)

- Meta-analyses of psychosocial interventions in cardiac patients show ~19% lower cardiac mortality, ~21% lower MI, ~39% lower arrhythmias

- Mindfulness in coronary artery disease significantly reduces anxiety, depression, and stress

What coaches can do:

Stress management is squarely within coaching scope. You can support clients in:

- Identifying stress triggers and patterns

- Developing stress-reduction habits (breath work, mindfulness, nature exposure)

- Prioritizing sleep and recovery

- Setting boundaries and managing demands

- Building social connections (isolation is itself a CVD risk factor)

"Managing stress isn't soft advice. It's hardcore cardiovascular medicine. Chronic stress drives the same inflammatory processes that build arterial plaque. Taking your stress seriously is taking your heart health seriously."

Coaching in practice: Helping clients prioritize interventions¶

The scenario: A client reads about every possible heart-health intervention and feels overwhelmed about where to start.

What NOT to do:

❌ Hand them a long checklist of everything they "should" be doing right away.

Why it doesn't work: It reinforces all-or-nothing thinking and makes change feel impossible.

What TO do:

✅ Start with the biggest levers, then build gradually.

Sample dialogue:

Client: "There are so many things I could be doing for my heart—Zone 2, strength training, sodium, potassium, stress, sleep, fiber... I feel like I'm failing at all of it."

Coach: "It makes sense that you feel overwhelmed; there is a lot out there. We do not have to tackle everything at once. Think of it in tiers."

Client: "What do you mean by tiers?"

Coach: "Tier 1 is the foundation: not smoking, getting any regular movement if you're currently sedentary, and some basic food upgrades like more vegetables and less highly processed food. Once those feel solid, Tier 2 is building on the basics—meeting exercise guidelines, aiming for a Mediterranean-style eating pattern, and keeping an eye on blood pressure. Tier 3 is optimization: things like Zone 2 and VO2 max work, dialing in sodium and potassium, regular stress-management practices, and fine-tuning macros and fiber intake."

Client: "That feels more manageable."

Coach: "Great. You do not have to do everything at once. Let's identify one or two changes from Tier 1 or Tier 2 that feel realistic this week, and we can build from there."

Key takeaway: Organize heart-health behaviors into tiers, and help clients focus on one or two realistic changes instead of trying to optimize everything at once.

[CHONK: Section 4 - Medications: Educational Awareness]

Medications: Educational awareness¶

Why coaches need to understand cardiovascular medications¶

You will not prescribe or recommend medications. But you need to understand them for three reasons:

-

To support clients in their conversations with doctors. Clients often have questions about medications their doctors recommend. You can help them understand generally what medications do (educational) and encourage them to discuss concerns with their prescriber.

-

To support medication adherence. Nonadherence to cardiovascular medications increases mortality risk by 50-80%.[^34] Only about 51% of US adults treated for hypertension adhere as prescribed. Coaches can play a vital role in supporting adherence, without prescribing.

-

To recognize when lifestyle isn't enough. Some clients need medication alongside lifestyle changes. Understanding this helps you support (rather than undermine) medical recommendations.

Statins: What the evidence shows¶

Statins are the most prescribed cardiovascular medications and have the most evidence behind them. Here's what coaches should know: educationally.

How statins work:

Statins block an enzyme (HMG-CoA reductase) involved in cholesterol production, primarily lowering LDL-C and ApoB. They also have anti-inflammatory effects independent of cholesterol lowering.

The evidence for benefit:

Multiple meta-analyses establish statin benefits:[^35]

For all patients:

- Per 1 mmol/L (~39 mg/dL) LDL-C reduction: ~10% lower all-cause mortality, ~20% lower coronary mortality, ~22% lower major vascular events

For primary prevention (no prior heart disease):

- All-cause mortality: ~8% reduction (RR ~0.92)

- MI: ~33% reduction (RR ~0.67)

- Stroke: ~22% reduction (RR ~0.78)

- Composite CVD: ~28% reduction (RR ~0.72)

For secondary prevention (prior heart disease):

- Benefits are larger in absolute terms due to higher baseline risk

- High-intensity statins targeting ≥50% LDL-C reduction are standard of care

The absolute vs relative risk distinction:

Relative risk reductions sound impressive (~30% lower MI risk!), but absolute risk reductions depend on baseline risk. In low-risk primary prevention over 2-6 years:[^36]

- All-cause mortality: absolute reduction ~0.35%

- MI: absolute reduction ~0.85%

- Stroke: absolute reduction ~0.39%

These are modest in absolute terms for low-risk individuals over short follow-up. Benefits are larger for higher-risk individuals and likely accumulate over longer periods.

If these percentages feel confusing, that is okay. The main idea is that statins slightly lower the chances of heart attacks and strokes, especially for people whose starting risk is higher, and doctors weigh those potential benefits against side effects and patient preferences when they make recommendations.

Who benefits most:

Guidelines recommend statins for:[^37]

- Secondary prevention: Anyone with prior heart attack, stroke, or established atherosclerotic CVD

- Very high LDL-C: LDL ≥190 mg/dL regardless of other factors

- Diabetes: Ages 40-75 with diabetes

- Higher calculated risk: 10-year CVD risk ≥7.5-10% in ages 40-75

What coaches should NOT do:

- Recommend for or against statins

- Suggest clients stop or reduce statins

- Imply that lifestyle can replace statins (for some people, both are needed)

- Dismiss clients' concerns about side effects (these should be discussed with their doctor)

Other cardiovascular medications (brief overview)¶

Clients may mention other medications. Here's educational context:

Blood pressure medications:

- Multiple classes: ACE inhibitors, ARBs, calcium channel blockers, diuretics, beta-blockers

- Many people need 2+ medications to reach blood pressure goals

- Lifestyle changes can sometimes reduce (not replace) medication needs

Other lipid-lowering drugs:

- Ezetimibe: Blocks cholesterol absorption; often added to statins if LDL not at goal

- PCSK9 inhibitors: Powerful LDL lowering; expensive; typically for high-risk patients not at goal on statins

- Bempedoic acid, inclisiran: Newer options for those who can't tolerate statins

Blood thinners:

- Aspirin, clopidogrel, anticoagulants: For people with certain conditions or procedures

- These carry bleeding risks; never advise on these

Supporting medication adherence¶

This IS within coaching scope. It matters enormously.

Why adherence matters:

Nonadherence to cardioprotective medications increases death risk by 50-80%. Effective two-way communication doubles the odds of proper medication taking.[^38]

What coaches can do:

-

Explore barriers without judgment. "Tell me about how taking your medications fits into your day."

-

Problem-solve logistics. "It sounds like remembering the evening dose is the hard part. What might help with that?"

-

Support client-doctor communication. "If the side effects are bothering you, that's really important to discuss with your doctor. They may be able to adjust the dose or try a different medication."

-

Reinforce the why. "I know taking pills every day doesn't feel like it's doing anything. But these medications are working quietly in the background to protect your heart."

-

Don't undermine medical advice. If a client says "I read statins are bad," respond: "There's a lot of conflicting information out there. What did your doctor say about why they recommended it? That might be worth discussing with them directly."

Motivational interviewing works:

Meta-analyses show that motivational interviewing for hypertension reduces SBP by ~6.6 mmHg and DBP by ~3.8 mmHg vs minimal intervention, with some studies also showing improved adherence.[^39] The skills you're developing as a coach directly apply here.

Coaching in practice: Responding to medication concerns¶

Clients will often have strong feelings about cardiovascular medications. Your job is to stay in scope while helping them feel heard and supported.

Scenario 1: "I read that statins have a lot of side effects."

What NOT to do:

❌ Tell them, "That's not true, just take the pill," or, on the other side, "You're right, statins are dangerous."

Why it doesn't work: Dismissing concerns harms trust, and agreeing that a prescribed medication is "bad" pulls you outside your scope.

What TO do:

✅ Normalize their desire to be informed, share general education, and point them back to their prescriber.

Sample dialogue:

Client: "I read that statins have a lot of side effects."

Coach: "There is definitely a lot of information out there, and it's smart that you're asking questions. Research shows that many reported side effects are not actually caused by the medication. There is also a strong nocebo effect, where expecting side effects can make them more likely. At the same time, some people do experience real muscle symptoms, and your doctor is the best person to help you sort out what's going on for you. Have you had a chance to talk with them about your concerns?"

Scenario 2: "I want to lower my cholesterol naturally."

What NOT to do:

❌ Promise that lifestyle changes will definitely let them avoid medication.

Why it doesn't work: For some people, genetics and overall risk mean medications plus lifestyle are the safest option.

What TO do:

✅ Channel their motivation into behavior change while keeping medication decisions with the doctor.

Sample dialogue:

Client: "I want to lower my cholesterol naturally. I really don't want to be on meds."

Coach: "I love that you're motivated to work on lifestyle. Diet, movement, and fiber can absolutely help, and those are things we can work on together. For some people, lifestyle alone is enough; for others, especially if their risk is higher, medications plus lifestyle work better than either one alone. Your doctor can help you understand what makes sense for your specific situation."

Scenario 3: "I stopped taking my blood pressure medicine because I feel fine."

What NOT to do:

❌ Reassure them that feeling fine means they no longer need the medication.

Why it doesn't work: High blood pressure is often symptomless until serious problems occur, and advising about stopping meds is outside your scope.

What TO do:

✅ Explain why "feeling fine" is not a reliable indicator and strongly encourage medical follow-up.

Sample dialogue:

Client: "I stopped taking my blood pressure medicine because I feel fine."

Coach: "High blood pressure is sometimes called the 'silent killer' because it usually does not cause symptoms until something serious happens. Feeling fine does not necessarily mean your blood pressure is controlled; it just means your body is tolerating it for now. I would strongly encourage you to talk with your doctor before staying off the medication. Was there anything in particular that made you stop—side effects, cost, or something else?"

Key takeaway: Stay curious and supportive, offer clear general education, and always direct decisions about starting, stopping, or changing medications back to the prescribing clinician.

[CHONK: Section 5 - Coaching Cardiovascular Health]

Coaching cardiovascular health¶

When to refer to cardiologists¶

Knowing when to refer is as important as knowing how to help. Here are clear criteria:

Immediate/emergency referral (call 911):[^40]

- Suspected heart attack: Chest pain/pressure, pain radiating to arm/jaw/back, shortness of breath, cold sweat, nausea

- Suspected stroke: FAST. Face drooping, Arm weakness, Speech difficulty, Time to call 911

- Hypertensive emergency: BP ≥180/120 mmHg WITH chest pain, shortness of breath, back pain, or neurologic symptoms (numbness, weakness, vision changes)

- Collapse or unresponsiveness

- Severe irregular heartbeat with chest pain or fainting

Same-day medical referral:

- New or worsening chest pain that sounds ischemic, meaning caused by reduced blood flow to the heart (pressure, heaviness, worse with exertion, radiating to arm/jaw)

- Chest pain at rest or increasing in frequency

- Fainting during exercise or with palpitations

- Fainting in anyone with known heart disease or family history of sudden cardiac death

- Rapid weight gain (>2-3 lbs/day or >5 lbs/week) in someone with heart failure

- New shortness of breath at rest or when lying down

- New leg pain with walking that resolves with rest (possible peripheral artery disease)

- Palpitations with chest pain, fainting, or shortness of breath

Routine referral (schedule with their doctor):

- Blood pressure consistently elevated on home monitoring

- Labs showing concerning patterns (per their doctor)

- New cardiac symptoms not requiring urgent care

- Questions about medications, testing, or treatment

Session stop rules:

If during a coaching session (especially if discussing exercise):

- Client reports severe resting BP (>200/110 mmHg)

- Client describes chest pain or pressure

- Client appears confused, pale, sweaty, or distressed

- Client describes symptoms that sound cardiac

Stop the session and direct them to seek medical attention.

Supporting clients with known CVD¶

Many clients will already have diagnosed cardiovascular disease: prior heart attack, stent, bypass surgery, heart failure, etc. Here's how to support them appropriately.

What's different:

These clients are in secondary prevention. Their risk is higher, so interventions matter more (in absolute terms). They're typically on multiple medications and may have specific restrictions from their cardiologist.

What coaches can do:

-

Coordinate with the medical team. "What has your cardiologist said about exercise? Any restrictions I should know about?"

-

Support cardiac rehabilitation participation. Cardiac rehab is evidence-based and underutilized. Encourage completion.

-

Focus on adherence. Medication adherence is critical in this population. Support it consistently.

-

Monitor for warning signs. Know the symptoms that require urgent attention (see above).

-

Support lifestyle aggressively. Secondary prevention guidelines recommend intensive lifestyle intervention alongside medications.

What coaches cannot do:

- Design exercise programs for cardiac patients (this requires clinical expertise)

- Modify medication schedules or timing

- Clear clients for activities their cardiologist hasn't approved

- Make assumptions about what's safe

If supporting clients with known heart disease feels intimidating, that's understandable. Remember that you are not replacing their cardiologist; you're helping them follow through on medical advice and make sustainable lifestyle changes, which is an enormously valuable role.

Behavior change for heart health¶

The coaching skills you've developed throughout this program apply directly to cardiovascular health. Some specific considerations:

Addressing invincibility thinking:

Many clients, especially younger ones, don't feel personally at risk for heart disease. Atherosclerosis starts in childhood but doesn't cause symptoms for decades. Help clients understand they're building (or preventing) tomorrow's disease today.

"Heart disease develops over 30-40 years before causing problems. The plaque in someone's arteries at age 55 started forming in their 20s and 30s. What you do now isn't about immediate symptoms. It's about where you'll be in 20 years."

Working with fear:

Other clients may be anxious about heart disease, especially with family history. Balance urgency with empowerment.

"I hear that you're worried, especially given what happened to your dad. Here's what's encouraging: even with family history, the majority of risk comes from modifiable factors. You're not powerless. You're actually in a position to change your trajectory."

The Deep Health connection:

Cardiovascular health connects to all dimensions of Deep Health:

- Physical: Obviously, the cardiovascular system itself

- Emotional: Stress, anxiety, and depression affect heart health directly

- Environmental: Air pollution is a cardiovascular risk factor; so is noise pollution

- Social: Social isolation and loneliness increase cardiovascular risk

- Existential: A sense of purpose is associated with better cardiovascular outcomes

- Mental/Cognitive: Cognitive decline and cardiovascular disease share risk factors

A whole-person approach to coaching naturally supports heart health.

Case study: Coaching cardiovascular risk¶

Client profile: Michael, 52, recently told by his doctor that his cholesterol is "borderline high" and blood pressure is "elevated." His doctor recommended lifestyle changes before considering medication. He has a family history of heart disease (father had a heart attack at 58). He's currently sedentary, eats a typical American diet, works a stressful job, and sleeps about 5-6 hours per night.

What this looks like in practice:

What NOT to do:

❌ Immediately jump into telling Michael exactly what exercise and diet plan he should follow without understanding his context or what his doctor said.

Why it doesn't work: You might miss important medical information, choose goals that don't fit his life, or accidentally contradict his doctor's advice.

What TO do:

✅ Get curious about the medical conversation, explore current habits, and co-create small, specific next steps.

Sample dialogue:

Coach: "Tell me more about what your doctor said. What numbers did they share, and what did they recommend?"

Michael: "They said my cholesterol is 'borderline high' and my blood pressure is 'elevated.' They want me to work on diet and exercise for a few months before we talk meds."

Coach: "Thanks for filling me in. Before we set any goals, I'd love to understand what life looks like for you right now—eating, movement, stress, sleep. What's working well, and what's feeling tough?"

Michael: "Honestly, I'm not exercising at all, my job is stressful, and I grab a lot of takeout. I only sleep about five or six hours most nights."

Coach: "Given everything on your plate, that makes sense. There are lots of areas we could work on. When you think about your heart health and your family history, what feels most important to start with?"

Michael: "Probably moving more. My doctor seemed really focused on that."

Coach: "Great. Instead of 'exercise more,' how would you feel about starting with something specific, like a 20-minute walk three times this week? We can also look at one simple food change, like adding a serving of vegetables to lunch."

Michael: "That sounds doable."

Coach: "And with your dad's heart history, it's completely understandable that this is on your mind. The fact that you're taking action now puts you in a different position from someone who ignores those early warning signs. Before your next appointment, we can also jot down any questions you want to ask about your numbers and what targets make sense for you."

Key takeaway: Use Michael's medical information and family history to guide the conversation, but stay focused on understanding his context and helping him choose small, doable behavior changes.

What the coach cannot do:

- Tell Michael his specific numbers are "fine" or "concerning"

- Recommend specific supplements for cholesterol

- Design an exercise program (refer to a qualified professional)

- Advise against medication if his doctor eventually recommends it

Coaching in practice: Family history conversations¶

Many clients have family history of heart disease and may feel fatalistic ("My dad had a heart attack, so I probably will too") or anxious. Here's how to have scope-appropriate, empowering conversations.

The scenario: A client with a parent who had a heart attack says, "My dad had a heart attack, so I feel like it's just a matter of time for me."

What NOT to do:

❌ Either brush off their worry ("Oh, you'll be fine") or, on the other extreme, confirm their worst fears.

Why it doesn't work: Minimizing feelings breaks trust, and reinforcing fatalism makes change feel pointless.

What TO do:

✅ Acknowledge that family history matters, then highlight the power of lifestyle.

Sample dialogue:

Client: "My dad had a heart attack at 58, so I feel like it's just a matter of time for me."

Coach: "Given what happened to your dad, it makes total sense that you'd be worried. Family history does matter—it can increase risk. At the same time, research shows that even people with higher genetic risk see big benefits from healthy lifestyle choices."

Client: "Really? Even if my genes are bad?"

Coach: "Yes. One large study found that people with high genetic risk who followed healthy lifestyle habits cut their cardiovascular risk by nearly half. Your genes are part of the story, but they are not your destiny."

Client: "That makes me feel like there's something I can do."

Coach: "Exactly. What you're doing right now—paying attention and making changes—is how you write a different story than your family history might suggest. If you ever have questions about genetic testing, that's something to explore with your doctor, and I can support you in following whatever plan you come up with together."

Key takeaway: Validate clients' fears about family history while reinforcing that lifestyle changes can meaningfully shift risk; keep any testing or treatment decisions with the medical team.

Study guide questions¶

-

Approximately what percentage of cardiovascular disease risk is attributed to modifiable factors? Why is this significant for coaching?

-

Describe the basic process of atherosclerosis development. Why does understanding this help coaches explain lifestyle interventions?

-

What is ApoB, and why do many experts consider it superior to LDL cholesterol for assessing cardiovascular risk?

-

Name three lifestyle interventions that lower blood pressure and describe the approximate magnitude of effect for each.

-

What are the scope boundaries for coaches discussing cardiac biomarkers? Give an example of scope-appropriate vs. scope-inappropriate language.

-

Describe the evidence linking chronic stress to cardiovascular disease. What mechanisms connect stress to heart health?

-

What are the referral criteria for cardiovascular emergencies vs. same-day medical evaluation vs. routine referral?

-

How can coaches support medication adherence without prescribing or recommending medications?

-

What is the Mediterranean diet, and what does the evidence show about its cardiovascular benefits?

-

Describe how you would apply Deep Health principles when coaching a client with cardiovascular risk factors.

Self-reflection questions:

-

When did you last have your blood pressure checked? Do you know your numbers? If not, consider getting a baseline this month.

-

Looking at your own cardiovascular risk factors (family history, current lifestyle, stress level), which one lifestyle change would have the biggest impact on your heart health?

Chapter 16 exam¶

1. According to global statistics, cardiovascular disease accounts for approximately what percentage of all deaths worldwide?

- A) 10-15%

- B) 20-25%

- C) 30-33%

- D) 40-45%

2. Which of the following best describes ApoB?

- A) A type of cholesterol found only in LDL particles

- B) A protein found on all atherogenic lipoproteins that allows particle counting

- C) An enzyme that breaks down cholesterol in the liver

- D) A genetic marker for inherited heart disease

3. A coach's role regarding cardiac biomarkers is to:

- A) Interpret results and tell clients if numbers are concerning

- B) Recommend specific supplements to improve numbers

- C) Explain what biomarkers measure without interpreting specific values

- D) Advise clients on whether they need medication based on results

4. Which lifestyle intervention has shown approximately 8-14 mmHg reduction in systolic blood pressure in hypertensive adults?

- A) Taking vitamin D supplements

- B) Regular aerobic exercise

- C) Increasing saturated fat intake

- D) Taking magnesium supplements

5. According to research on stress and cardiovascular health, chronic stress increases CVD risk through which mechanism(s)?

- A) Elevated cortisol and inflammatory pathways

- B) Direct damage to heart muscle fibers

- C) Reduction in red blood cell count

- D) Increased vitamin absorption

6. A client tells you they stopped taking their blood pressure medication because they "feel fine." The appropriate coaching response is:

- A) Agree that if they feel fine, they probably don't need the medication

- B) Explain that high blood pressure usually has no symptoms and strongly encourage them to talk to their doctor before stopping

- C) Recommend they switch to natural alternatives

- D) Tell them their doctor was probably wrong to prescribe it

7. Which statement about statins is accurate?

- A) Coaches can recommend statins for clients with high LDL

- B) Research shows statins reduce major vascular events by approximately 20-22% per 1 mmol/L LDL reduction

- C) Statins only benefit people who have already had a heart attack

- D) Lifestyle changes should always replace statins rather than complement them

8. A client reports having chest tightness that comes on when walking up stairs and goes away with rest. You should:

- A) Recommend they reduce their stair climbing until the tightness stops

- B) Recognize this as a potential cardiac symptom requiring same-day medical evaluation and direct them to seek care

- C) Tell them it's probably just deconditioning and will improve with exercise

- D) Wait to see if it happens again before taking action

9. The Mediterranean diet has shown evidence of reducing cardiovascular events by approximately:

- A) 5-10%

- B) 20-25%

- C) 40-50%

- D) 70-80%

10. When supporting a client with known cardiovascular disease, a coach should:

- A) Design their exercise program based on general fitness principles

- B) Coordinate with the client's medical team and support completion of cardiac rehabilitation

- C) Recommend they discontinue cardiac medications if lifestyle changes improve their numbers

- D) Avoid discussing lifestyle changes since they're already under medical care

Answer key: 1-C, 2-B, 3-C, 4-B, 5-A, 6-B, 7-B, 8-B, 9-C, 10-B

Works cited¶

References¶

-

World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) fact sheet. WHO; 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds)

-

Jebari-Benslaiman S, Galicia-García U, Larrea-Sebal A, Olaetxea JR, Alloza I, Vandenbroeck K, et al. Pathophysiology of Atherosclerosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23(6):3346. doi:10.3390/ijms23063346

-

MacRae SM, et al.. The role of lipids and lipoproteins in atherosclerosis. Endotext; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK343489/

-

Cockerill G, Xu Q. Atherosclerosis. Mechanisms of Vascular Disease. 2011:25-42. doi:10.1017/upo9781922064004.004

-

Pahwa R, Jialal I. Atherosclerosis. StatPearls; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507799/

-

Ajoolabady A, Pratico D, Lin L, Mantzoros CS, Bahijri S, Tuomilehto J, et al. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: pathophysiology and mechanisms. Cell Death & Disease. 2024;15(11). doi:10.1038/s41419-024-07166-8

-

Magnussen CG, et al.. Global impact of modifiable risk factors on cardiovascular disease and mortality. N Engl J Med; 2023. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37632466/

-

Kariuki JK, Imes CC, Engberg SJ, Scott PW, Klem ML, Cortes YI. Impact of lifestyle-based interventions on absolute cardiovascular disease risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JBI Evidence Synthesis. 2023;22(1):4-65. doi:10.11124/jbies-22-00356

-

Wu J, Feng Y, Zhao Y, Guo Z, Liu R, Zeng X, et al. Lifestyle behaviors and risk of cardiovascular disease and prognosis among individuals with cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 71 prospective cohort studies. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2024;21(1). doi:10.1186/s12966-024-01586-7

-

van Trier TJ, Mohammadnia N, Snaterse M, Peters RJG, Jørstad HT, Bax WA. Lifestyle management to prevent atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: evidence and challenges. Netherlands Heart Journal. 2021;30(1):3-14. doi:10.1007/s12471-021-01642-y

-

Cole J, Zubirán R, Wolska A, Jialal I, Remaley A. Use of Apolipoprotein B in the Era of Precision Medicine: Time for a Paradigm Change?. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023;12(17):5737. doi:10.3390/jcm12175737

-

Sniderman AD, Dufresne L, Pencina KM, Bilgic S, Thanassoulis G, Pencina MJ. Discordance among apoB, non–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides: implications for cardiovascular prevention. European Heart Journal. 2024;45(27):2410-2418. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehae258

-

Soffer DE, Marston NA, Maki KC, Jacobson TA, Bittner VA, Peña JM, et al. Role of apolipoprotein B in the clinical management of cardiovascular risk in adults: An Expert Clinical Consensus from the National Lipid Association. Journal of Clinical Lipidology. 2024;18(5):e647-e663. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2024.08.013

-

Cao J, Donato L, El-Khoury JM, Goldberg A, Meeusen JW, Remaley AT. ADLM Guidance Document on the Measurement and Reporting of Lipids and Lipoproteins. The Journal of Applied Laboratory Medicine. 2024;9(5):1040-1056. doi:10.1093/jalm/jfae057

-

Jones DW, Ferdinand KC, Taler SJ, Johnson HM, Shimbo D, Abdalla M, et al. 2025 AHA/ACC/AANP/AAPA/ABC/ACCP/ACPM/AGS/AMA/ASPC/NMA/PCNA/SGIM Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. JACC. 2025;86(18):1567-1678. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2025.05.007

-

American Heart Association. 2025 High blood pressure guideline: top 10 things to know. Professional Heart Daily; 2025. https://professional.heart.org/en/science-news/2025-high-blood-pressure-guideline-top-10-things-to-know

-

European Society of Cardiology. New ESC hypertension guidelines recommend intensified BP targets. ESC Press; 2024. https://www.escardio.org/The-ESC/Press-Office/Press-releases/new-esc-hypertension-guidelines-recommend-intensified-bp-targets

-

Mortensen MB, et al.. Population-based recalibration of FRS and PCEs. J Am Coll Cardiol; 2022. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35926934/

-

Diao JA, Shi I, Murthy VL, Buckley TA, Patel CJ, Pierson E, et al. Projected Changes in Statin and Antihypertensive Therapy Eligibility With the AHA PREVENT Cardiovascular Risk Equations. JAMA. 2024;332(12):989. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.12537

-

White-Al Habeeb NMA, Higgins V, Wolska A, Delaney SR, Remaley AT, Beriault DR. The Present and Future of Lipid Testing in Cardiovascular Risk Assessment. Clinical Chemistry. 2023;69(5):456-469. doi:10.1093/clinchem/hvad012

-

Lim AY, Chen Y, Hsu C, Fu T, Wang J. The Effects of Exercise Training on Mitochondrial Function in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23(20):12559. doi:10.3390/ijms232012559

-

Kazemi A, Soltani S, Aune D, Hosseini E, Mokhtari Z, Hassanzadeh Z, et al. Leisure-time and occupational physical activity and risk of cardiovascular disease incidence: a systematic-review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2024;21(1). doi:10.1186/s12966-024-01593-8

-

Cornelissen VA, Smart NA. Exercise Training for Blood Pressure: A Systematic Review and Meta‐analysis. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2013;2(1). doi:10.1161/jaha.112.004473

-

Sebastian SA, Padda I, Johal G. Long-term impact of mediterranean diet on cardiovascular disease prevention: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Current Problems in Cardiology. 2024;49(5):102509. doi:10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2024.102509

-

Ghavami A, Ziaei R, Talebi S, Barghchi H, Nattagh-Eshtivani E, Moradi S, et al. Soluble Fiber Supplementation and Serum Lipid Profile: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Advances in Nutrition. 2023;14(3):465-474. doi:10.1016/j.advnut.2023.01.005

-

Gupta DK, Lewis CE, Varady KA, Su YR, Madhur MS, Lackland DT, et al. Effect of Dietary Sodium on Blood Pressure. JAMA. 2023;330(23):2258. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.23651

-

Neal B, Wu Y, Feng X, Zhang R, Zhang Y, Shi J, et al. Effect of Salt Substitution on Cardiovascular Events and Death. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;385(12):1067-1077. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2105675

-

Hooper L, Martin N, Abdelhamid A, Davey Smith G. Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011737

-

Li Y, Hruby A, Bernstein AM, Ley SH, Wang DD, Chiuve SE, et al. Saturated Fats Compared With Unsaturated Fats and Sources of Carbohydrates in Relation to Risk of Coronary Heart Disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2015;66(14):1538-1548. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.055

-

Santosa A, Rosengren A, Ramasundarahettige C, Rangarajan S, Gulec S, Chifamba J, et al. Psychosocial Risk Factors and Cardiovascular Disease and Death in a Population-Based Cohort From 21 Low-, Middle-, and High-Income Countries. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(12):e2138920. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.38920

-

Dar T, Radfar A, Abohashem S, Pitman RK, Tawakol A, Osborne MT. Psychosocial Stress and Cardiovascular Disease. Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2019;21(5). doi:10.1007/s11936-019-0724-5

-

Webster KE, Halicka M, Bowater RJ, Parkhouse T, Stanescu D, Punniyakotty AV, et al. Effectiveness of stress management and relaxation interventions for management of hypertension and prehypertension: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ Medicine. 2025;4(1):e001098. doi:10.1136/bmjmed-2024-001098

-

Million Hearts. Improving medication adherence among patients with hypertension. CDC/CMS; 2024. https://millionhearts.hhs.gov/tools-protocols/tools/medication-adherence.html

-

Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaboration . Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170 000 participants in 26 randomised trials. The Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670-1681. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61350-5

-

Chou R, Cantor A, Dana T, Wagner J, Ahmed AY, Fu R, et al. Statin Use for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults. JAMA. 2022;328(8):754. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.12138

-

USPSTF. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: recommendation statement. JAMA; 2022. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36006638/

-

Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, Hobson N, Jeffery R, Keepanasseril A, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;2014(11). doi:10.1002/14651858.cd000011.pub4

-

Rubak S, et al.. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract; 2005. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1463134/

-

American Heart Association. Hypertensive crisis: when you should call 911 for high blood pressure. 2025. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/understanding-blood-pressure-readings/hypertensive-crisis-when-you-should-call-911-for-high-blood-pressure

-

American Stroke Association. Stroke symptoms and warning signs. 2025. https://www.stroke.org/en/about-stroke/stroke-symptoms