Unit 2: Core Interventions (The Protocol)¶

Chapter 2.8: Metabolic Health & Nutrition Timing¶

[CHONK: 1-minute summary]

What you'll learn in this chapter:

- What metabolic health actually means and why it matters for longevity

- Metabolic flexibility: your body's ability to switch between fuel sources (and why it declines with age)

- Practical blood sugar management strategies coaches can implement

- Time-restricted eating: evidence, protocols, and appropriate caveats

- Gender-specific considerations for fasting (understandable for all coaches)

- When metabolic concerns require medical referral

- How to coach these interventions without creating obsession or fear

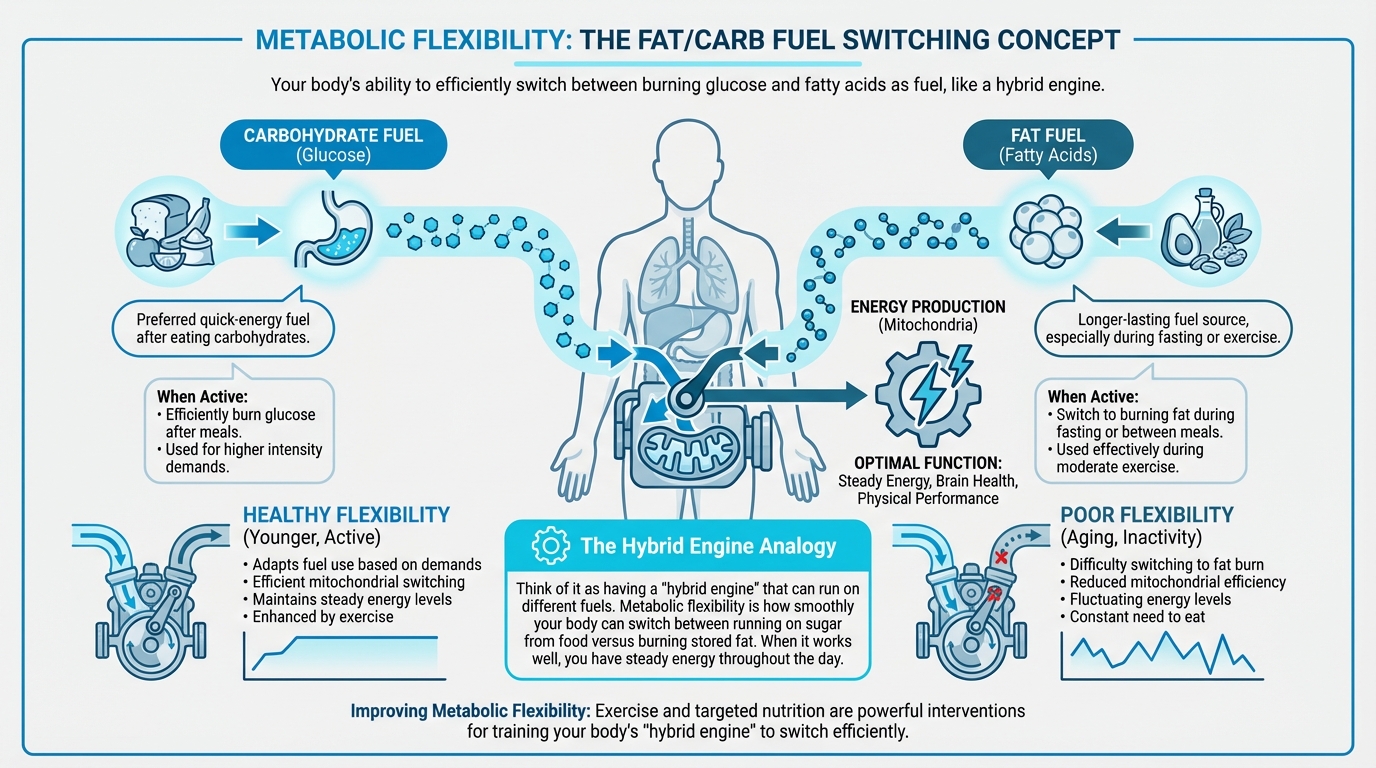

Figure: Fat/carb fuel switching concept

The big idea: This chapter is about when and how to eat. Complementing Chapter 2.7's focus on what to eat. Meal timing and metabolic health are real factors in longevity, but they're often overhyped in optimization culture. Here, we'll separate evidence from enthusiasm, give you practical strategies that work, and keep you firmly within coaching scope. The hierarchy matters: fundamentals first, timing optimization second.

[CHONK: Introduction: Why Meal Timing Matters (and Why It's Not Magic)]

Introduction: It's Not Just What You Eat¶

"I'm doing 16:8 fasting for longevity." "I bought a CGM to optimize my metabolism." "Should I be worried about glucose spikes?"

Clients come with a lot of ideas about meal timing—some useful, some overhyped. This chapter helps you sort the signal from the noise.

In Chapter 2.7, we covered what to eat. This chapter covers when to eat and how to support metabolic health. The bottom line: timing matters, but fundamentals matter more.

The Hierarchy: What Actually Matters¶

Here's the priority order (and it's not negotiable):

Essential (must be in place first):

- Adequate protein distributed across meals (Chapter 2.7)

- Sufficient vegetables and fiber

- Adequate sleep (Chapter 2.11)

- Regular movement (Chapter 2.9)

Valuable (add once essentials are solid):

- Post-meal walks for blood sugar management

- Pairing protein/fat/fiber with carbohydrates

- Basic overnight fasting (12 hours, which most people already do)

Advanced/Individual (fine-tuning for those with fundamentals dialed):

- Extended time-restricted eating windows (14-16 hours)

- Detailed blood sugar tracking

- Metabolic flexibility protocols

This hierarchy matters. If someone's eating processed foods for most meals, skipping breakfast won't save them. If someone's sleeping poorly and sedentary, extending their fasting window won't compensate. Fundamentals first.

What This Chapter Covers vs. What It Doesn't¶

We will cover:

- Metabolic health concepts coaches can explain to clients

- Practical strategies (post-meal walks, meal composition, timing)

- Time-restricted eating with honest evidence assessment

- Gender-specific considerations without over-medicalizing

- Clear scope boundaries for metabolic health coaching

We won't cover:

- Extended fasting protocols (24+ hours). Insufficient evidence, medical territory

- Detailed metabolic disease management. Scope of dietitians and physicians

- Specific supplement protocols for metabolic health (beyond scope of this chapter)

- Dramatic claims about "metabolic magic"

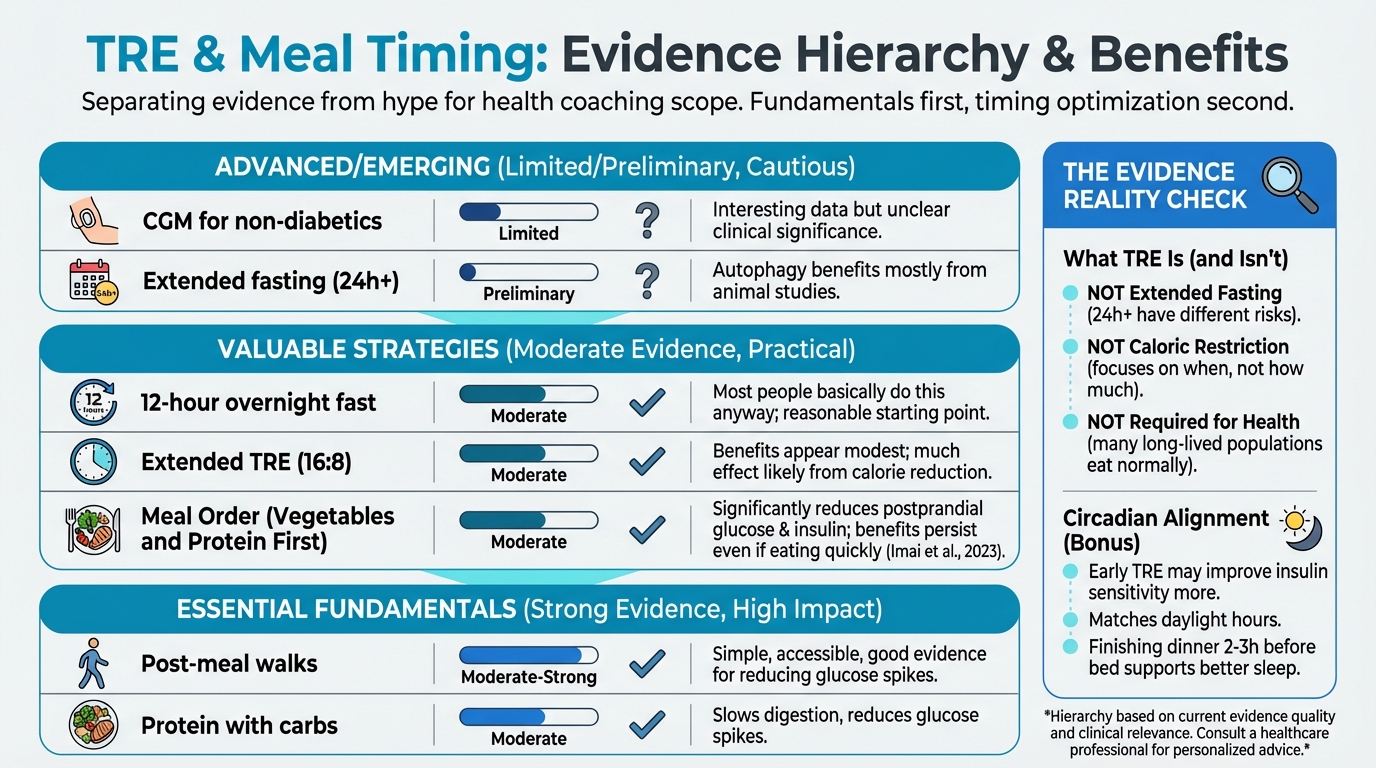

The Evidence Reality Check¶

Here's an honest assessment of what we know:

| Intervention | Evidence Quality | Reality |

|---|---|---|

| Post-meal walks | Moderate-Strong | Simple, accessible, good evidence for reducing glucose spikes |

| Protein with carbs | Moderate | Slows digestion, reduces glucose spikes |

| 12-hour overnight fast | Moderate | Most people basically do this anyway; reasonable starting point |

| Extended TRE (16:8) | Moderate | Benefits appear modest; much effect likely from calorie reduction |

| CGM for non-diabetics | Limited | Interesting data but unclear clinical significance |

| Extended fasting (24h+) | Preliminary | Autophagy benefits mostly from animal studies |

Figure: TRE benefits with evidence strength

Keep this table in mind as we proceed. We're presenting useful strategies, not metabolic miracles.

[CHONK: Understanding Metabolic Health]

Understanding Metabolic Health¶

When clients say they want to "improve their metabolism" or "optimize metabolic health," what do they actually mean? Let's define these concepts clearly so you can explain them, and know when something crosses into medical territory.

What Is Metabolic Health?¶

Metabolism refers to all the chemical processes that convert food into energy and building blocks for cells. When we talk about metabolic health, we mean how well these systems function, particularly how the body regulates blood sugar, stores and uses fat, and maintains energy balance.

Clinically, metabolic health is often assessed through five markers. Having three or more markers outside healthy ranges is called metabolic syndrome: a cluster of conditions that increase risk for heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes:

| Marker | Healthy Range | Risk Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Waist circumference | <35" women, <40" men | Above these |

| Triglycerides | <150 mg/dL | ≥150 mg/dL |

| HDL cholesterol | >50 women, >40 men | Below these |

| Blood pressure | <130/85 mmHg | ≥130/85 mmHg |

| Fasting glucose | <100 mg/dL | ≥100 mg/dL |

Scope note: Coaches cannot diagnose metabolic syndrome. That requires lab interpretation by a healthcare provider. But understanding these markers helps you recognize when clients may need referral.

Metabolic Flexibility: The Core Concept¶

Metabolic flexibility is your body's ability to switch between different fuel sources depending on what's available. Think of it as having a "hybrid engine" that can run on different fuels:

- Glucose (from carbohydrates): Your body's preferred quick-energy fuel

- Fatty acids (from stored fat): A longer-lasting fuel source, especially during fasting or exercise

A metabolically flexible person can:

- Burn glucose efficiently after eating carbohydrates

- Switch to burning fat during fasting or between meals

- Use fat effectively during moderate exercise

- Adapt fuel use based on energy demands

Why Metabolic Flexibility Matters for Aging¶

Research shows that metabolic flexibility declines with age through several mechanisms:

Mitochondrial changes: Your mitochondria—the cellular "power plants" that produce energy—become less efficient at switching between fuel sources. Studies show that aging reduces activity of CPT1B, a key enzyme for fat oxidation, making it harder for older muscles to burn fat under lipid load (Vieira-Lara et al., 2021).

Insulin resistance: With age, cells often become less responsive to insulin's signal to take up glucose. This impairs the ability to clear blood sugar after meals and shifts metabolism toward constant glucose burning rather than flexible fuel switching.

Sedentary effects: Inactivity compounds age-related changes. Exercise is the most powerful intervention for maintaining metabolic flexibility, as it trains mitochondria to switch efficiently between fuels.

Signs of Poor Metabolic Flexibility¶

Clients with reduced metabolic flexibility may experience:

- Energy crashes between meals (can't access stored fat efficiently)

- Carbohydrate dependency (feeling like they "need" carbs to function)

- Difficulty fasting even for short periods without feeling terrible

- Afternoon slumps despite adequate sleep

- Weight gain concentrated around the midsection

These aren't diagnostic, and many factors cause these symptoms; still, they can prompt conversations about eating patterns and activity.

The Good News: Exercise Restores It¶

Here's what the research tells us: Exercise is the most powerful intervention for metabolic flexibility (Pan et al., 2025). Specifically:

- Resistance training ranks highest for improving overall insulin sensitivity

- Cycling ranks best for lowering fasting glucose

- Combined aerobic and resistance programs effectively lower insulin resistance markers

This connects directly to Chapter 2.9 (Exercise). The most reliable way to support metabolic health isn't timing tricks. It's regular movement.

The Build/Repair Connection¶

Remember from Chapter 2.7: your cells toggle between "build mode" (after eating) and "repair mode" (during fasting). Meal timing affects this rhythm.

Constant snacking keeps you in build mode all day, while overnight fasting lets repair mode happen. That's the basic science behind time-restricted eating—though the effects in humans are modest, not miraculous.

For the full biochemistry, see the Deep Dive: How Food Affects Aging Biology.

Coaching in Practice: Explaining Metabolic Flexibility¶

Client: "What does 'metabolic flexibility' even mean? I keep hearing about it."

Coach: "Think of your body like a hybrid car—it can run on either gasoline or electricity. Metabolic flexibility is how smoothly you switch between burning sugar from food versus burning stored fat. When it works well, you have steady energy all day. When it doesn't, you feel like you constantly need to eat to keep going."

Client: "That sounds like me. I crash if I don't eat every few hours."

Coach: "That's common, and it often improves with age and activity level. The single best thing for metabolic flexibility? Exercise. It trains your system to switch fuels more smoothly."

[CHONK: Blood Sugar Management]

Blood Sugar Management: Practical Strategies¶

Blood sugar regulation connects directly to aging biology. Chronic high blood sugar accelerates glycation (sugar molecules damaging proteins), promotes inflammation, and contributes to insulin resistance, all hallmarks of aging.

But here's the key: you don't need perfect blood sugar to age well. You need reasonable blood sugar management through simple, sustainable habits. This section covers evidence-based strategies coaches can implement within scope.

Why Blood Sugar Matters for Longevity¶

The connection between blood sugar and aging is well-established:

- Higher fasting glucose predicts higher risk of chronic disease and death

- Centenarians consistently show better blood sugar control than the general population

- Post-meal spikes drive more damage than modest sustained elevation

The practical implication: Strategies that reduce post-meal glucose spikes—even modest reductions—support healthier aging. You don't need perfection. You need reasonably good patterns.

Strategy 1: Post-Meal Walks¶

The most consistently supported intervention for blood sugar is simple: take a walk after eating.

Multiple studies confirm this works. Walking after meals reduces blood sugar significantly better than walking before meals or not walking at all. Even 10 minutes makes a measurable difference. Effects are strongest after dinner, when overnight glucose matters most.

Why it works: Walking activates your muscles, which pull sugar directly from your bloodstream without needing insulin. It's like opening a drain.

How to implement:

- Minimum: 10 minutes of easy walking after a meal

- Better: 15-20 minutes at a moderate pace

- Timing: Start within an hour of eating (sooner is better)

- Priority meal: Dinner

Coaching in Practice: Post-Meal Walks¶

Client: "I don't have time for a walk after every meal."

Coach: "It doesn't have to be 'exercise.' Walk the dog. Take the stairs. Park farther away. Even 10 minutes after dinner—when it matters most—makes a real difference for blood sugar."

Client: "Just 10 minutes?"

Coach: "That's enough to get your muscles pulling sugar out of your bloodstream. The goal is movement, not performance."

Strategy 2: Meal Order (Vegetables and Protein First)¶

Eating vegetables and protein before carbohydrates reduces postprandial glucose spikes. It's a simple reordering of what's already on your plate.

What the evidence shows:

A 2024 randomized crossover trial in gestational diabetes found that eating vegetables first, then protein, then carbohydrates reduced:

- 60-minute postprandial glucose by ~5.9%

- 120-minute postprandial glucose by ~6.1%

- Insulin response by ~8-11%

(Murugesan et al., 2024)

In healthy young women, eating vegetables first significantly reduced postprandial glucose and insulin at 30 and 60 minutes, and benefits persisted even when meals were eaten quickly (Imai et al., 2023).

How it works:

Vegetables and protein slow gastric emptying: the rate at which food leaves your stomach. When carbohydrates arrive more slowly in your small intestine, glucose enters your bloodstream more gradually, reducing the spike.

Practical implementation:

- Start meals with a salad or vegetable side

- Eat protein early in the meal

- Save starchy carbohydrates and bread for mid-to-late in the meal

- Don't obsess. General pattern matters more than precise sequencing

Strategy 3: Avoiding "Naked Carbs"¶

"Naked carbs" are carbohydrates eaten alone without protein, fat, or fiber. Think: a plain bagel, a handful of crackers, juice without anything else.

When carbohydrates are eaten alone, they're digested quickly, causing rapid blood sugar spikes. Pairing carbs with protein, fat, or fiber slows this process.

What the evidence shows:

A 2024 Frontiers in Nutrition study found that protein-rich, lower-carbohydrate meals produced smaller postprandial glucose peaks and lower glucose area-under-curve than iso-caloric high-carbohydrate or high-fiber meals (Ekberg et al., 2024).

A 2022 Nutrients review confirmed that adding protein or fat to carbohydrate meals slows gastric emptying, and viscous soluble fibers (like psyllium, pectin, or beta-glucan) slow carbohydrate absorption, both attenuating glucose spikes.

Practical implementation:

- Apple → Apple with almond butter

- Toast → Toast with eggs

- Rice bowl → Rice with chicken and vegetables

- Crackers → Crackers with cheese and vegetables

- Smoothie → Smoothie with protein powder or Greek yogurt

Coaching in Practice: "Dress Your Carbs"¶

Client: "Should I avoid carbs for blood sugar?"

Coach: "You don't have to avoid carbs—just don't eat them 'naked.' What I mean is: pair them with protein, fat, or fiber."

Client: "Like what?"

Coach: "Apple with almond butter instead of just an apple. Toast with eggs instead of just toast. Rice with chicken and vegetables instead of just rice. It slows digestion and smooths out your blood sugar. Same foods, just smarter combinations."

CGM Data: A Brief Mention¶

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) are devices that track blood sugar in real time. They're increasingly marketed to non-diabetic "wellness" consumers.

What coaches should know:

CGM data can reveal individual glucose responses to different foods, meals, and activities. For motivated clients, CGM can be an interesting educational tool to:

- See how different foods affect their blood sugar

- Notice the impact of post-meal walks

- Identify patterns (e.g., higher glucose after late-night meals)

However:

- Evidence for CGM improving hard outcomes (cardiovascular events, mortality) in non-diabetics is limited and preliminary (Ahmed et al., 2025; Wilczek et al., 2025)

- There's risk of creating obsession. Constantly checking numbers, anxiety over "spikes," avoiding foods unnecessarily

- Individual glucose readings vary for many reasons; focusing on single values can be misleading

Scope boundaries:

- CAN: Help clients notice patterns, correlate behaviors with glucose trends

- CANNOT: Interpret clinical significance of readings, diagnose conditions, recommend treatment

Coaching in Practice: "Should I Get a CGM?"¶

Client: "I've been seeing ads for CGMs. Should I get one to optimize my glucose?"

Coach: "They can be interesting as a learning tool—you'll see how walking after dinner really does flatten your glucose curve. But I'd be cautious about getting too focused on the numbers."

Client: "Why cautious?"

Coach: "The evidence that CGM improves long-term health for people without diabetes is still pretty limited. And some people get anxious chasing perfect readings. If you want to try it for a few weeks to see patterns, that's fine. Just remember the goal is building sustainable habits, not perfecting every glucose spike."

[CHONK: Time-Restricted Eating]

Time-Restricted Eating: Evidence Without Hype¶

Time-restricted eating (TRE) is one of the most discussed and most overhyped topics in longevity. Let's cut through the noise and present what we actually know.

What TRE Is (and Isn't)¶

Time-restricted eating means limiting food consumption to a specific window each day, typically 8-12 hours, with fasting for the remainder.

Common protocols:

- 12:12 = 12-hour eating window (e.g., 7am-7pm)

- 14:10 = 14-hour fast, 10-hour eating window

- 16:8 = 16-hour fast, 8-hour eating window

TRE is NOT:

- Extended fasting: 24+ hour fasts are different, with different evidence and risks

- Caloric restriction: TRE focuses on when you eat, not how much (though people often eat less with shorter windows)

- Required for health: Many healthy, long-lived populations eat normally without specific time restrictions

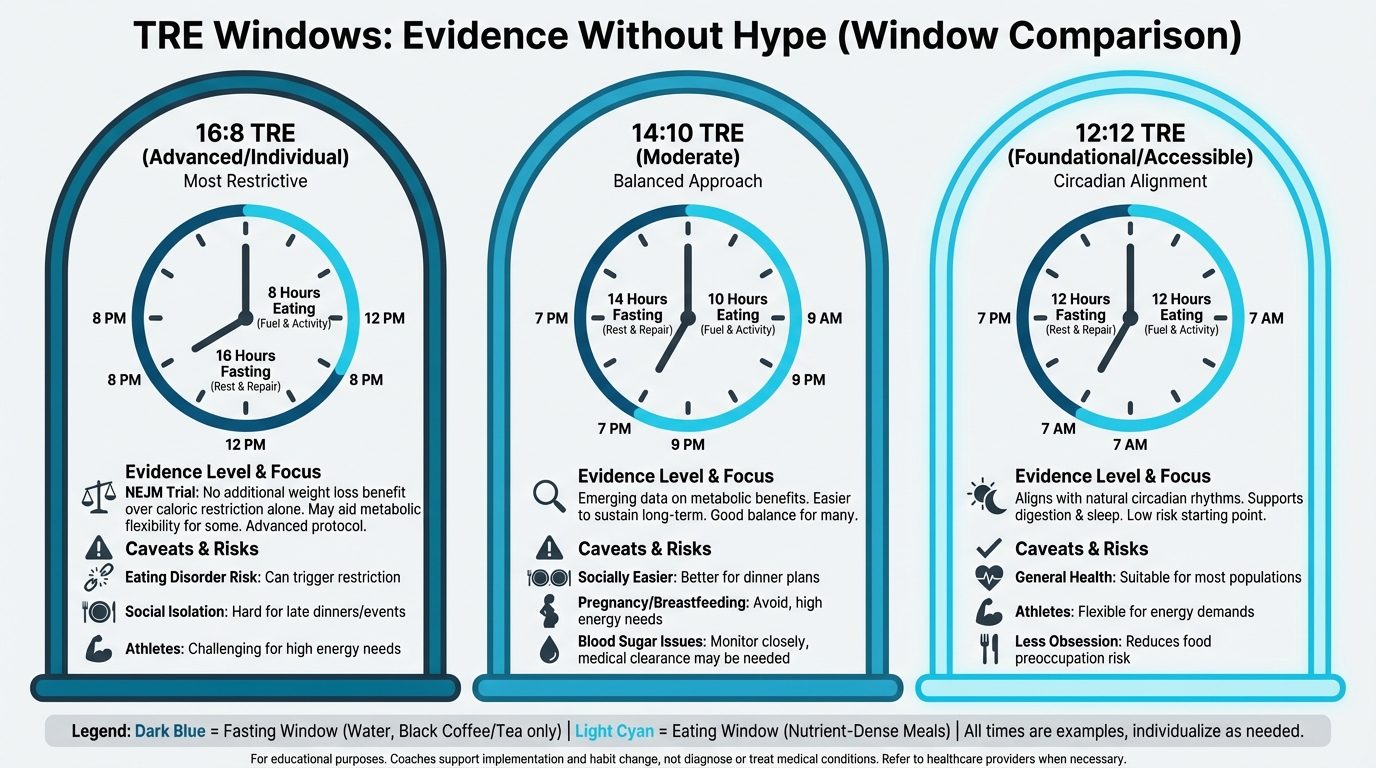

Figure: Different eating windows (16:8, 14:10, 12:12) with evidence levels

The Evidence: Modest Benefits, Likely From Calorie Reduction¶

Let's be honest about what the research shows:

Weight and body composition:

TRE consistently produces modest weight loss—approximately 1-2 kg—compared to unrestricted eating. Several meta-analyses confirm this:

- TRE alone vs. no restriction: weight -1.59 kg, fat mass -0.93 kg (IJBNPA, 2025)

- TRE in overweight/obese women: weight -1.93 kg (Frontiers in Nutrition, 2025)

- TRE combined with exercise: additional -1.86 kg vs. exercise alone (Advances in Nutrition, 2024)

But here's the catch:

A high-quality New England Journal of Medicine trial found that adding TRE to prescribed calorie restriction did not increase weight loss beyond calorie restriction alone (JAMA summary, 2023). In other words, when calories are controlled, the timing window itself doesn't add extra benefit.

This suggests much of TRE's effect comes from reduced calorie intake, not "metabolic magic."

Glycemic and metabolic markers:

- Frequent reductions in fasting insulin and insulin resistance markers (HOMA-IR, a calculation using fasting glucose and insulin to estimate insulin resistance)

- Some studies show improved HbA1c (a measure of average blood sugar over 2-3 months) in metabolic syndrome (1.7% greater reduction vs. control in one RCT)

- Effects on fasting glucose and lipids are inconsistent across studies

Circadian alignment:

Early time-restricted eating (eating earlier in the day, finishing dinner early) may provide additional benefits:

- Some studies show early TRE improves insulin sensitivity more than late TRE

- Eating aligned with daylight hours matches circadian biology

- Finishing dinner 2-3 hours before bed supports better sleep and overnight metabolism

Lean mass concerns:

- Several analyses report no significant lean mass loss with TRE

- Others report small reductions (~0.5 kg)

- Adequate protein and resistance training likely mitigate any losses

The Protocol: 12-16 Hour Overnight Fasts¶

Based on the evidence, here's a reasonable approach:

Starting point: 12 hours

Most people essentially do this already. Finishing dinner at 7pm and eating breakfast at 7am is a 12-hour fast. This is a sensible baseline that aligns with natural eating patterns.

Extension: 13-14 hours

For clients interested in extending their window, 13-14 hours is well-tolerated by most people:

- Dinner at 7pm, breakfast at 8-9am

- Or breakfast at 8am, dinner finished by 6-7pm

Advanced: 16 hours (16:8)

For clients who:

- Have solid nutrition fundamentals in place

- Tolerate extended fasting well

- Aren't prone to food preoccupation

- Don't have medical contraindications

A 16:8 window (e.g., noon-8pm eating) can be tried. But protein targets still matter. Cramming adequate protein into a short window is challenging.

The focus: When you stop eating

For most clients, the practical leverage point is dinner timing:

- Finish dinner 2-3 hours before bed

- Stop snacking after dinner

- Let overnight fasting happen naturally

Who Benefits, Who Should Be Cautious¶

May benefit from TRE:

- Those with solid nutrition fundamentals already in place

- Late-night snackers who want structure

- Those interested in simplifying meal timing

- Those who naturally aren't hungry in the morning

Caution or avoid TRE:

- History of eating disorders: TRE can trigger restrictive patterns

- Athletes with high energy demands: Hard to meet caloric needs in short windows

- Pregnant or breastfeeding: Energy needs are elevated; not the time for restriction

- Blood sugar issues requiring frequent eating: Some diabetics need regular meals

- Those who develop food preoccupation: If TRE creates anxiety, it's not worth it

- Clients on diabetes medications: Medication timing may need adjustment (medical referral)

The Honest Framing: One Tool, Not THE Tool¶

Here's how to present TRE to clients:

Coaching in Practice: The TRE Conversation¶

Client: "I want to try 16:8 fasting. I heard it's great for longevity."

Coach: "Before we go there, I want to check a few things. Are you hitting your protein targets? Getting enough vegetables? Sleeping well?"

Client: "I think so. Why?"

Coach: "Because those fundamentals matter more than your fasting window. Skipping breakfast to fast longer doesn't help if you're not getting adequate nutrition during your eating window. What does a typical day of eating look like for you?"

Client: "Honestly, I skip breakfast, have a light lunch, then eat a big dinner."

Coach: "So you're already doing something like 16:8—but you're probably back-loading most of your protein. Let's start there. If we get the fundamentals solid, then we can experiment with timing."

Coaching in Practice: When 16:8 Makes Sense¶

Client: "Okay, I've been hitting my protein targets for a month now. Can I try extending my fast?"

Coach: "Sure, let's try it. Start with finishing dinner by 7pm and not eating until 9am—that's a 14-hour fast. See how you feel after a week. If that goes well and you want to push to 16 hours, we can try that. But if it creates stress or makes you think about food constantly, it's not worth it. Health includes your relationship with food, not just metabolic markers."

[CHONK: Gender Considerations in Fasting]

Gender Considerations in Fasting¶

Men and women respond differently to fasting. This isn't about being overly cautious—it's biology. Whether you're male or female, you'll likely coach clients of all genders, and understanding these differences helps you give appropriate guidance.

The Core Difference¶

Women's bodies are more sensitive to energy restriction. When the body senses not enough food coming in, it prioritizes survival over reproduction—which means hormonal disruption, missed periods, and other downstream effects.

This isn't a small effect. Studies show sustained caloric restriction is the most common trigger for menstrual irregularities in otherwise healthy women.

The practical takeaway: The same fasting protocol that works fine for a male client may cause problems for a female client, so context matters.

The Exception: PCOS¶

Here's an important nuance: For women with PCOS (polycystic ovary syndrome), TRE often helps. Studies show improved menstrual regularity and better hormonal profiles. This makes sense—PCOS involves insulin resistance, and TRE's insulin-sensitizing effects can normalize hormone production.

The pattern: TRE may help women with metabolic dysfunction and hormone excess, while potentially harming women who are already lean or energy-restricted, so context matters.

Menstrual Cycle Considerations¶

For women who menstruate, the menstrual cycle affects energy needs and fasting tolerance:

Follicular phase (approximately days 1-14):

- Begins with menstruation, ends at ovulation

- Estrogen rises, progesterone is low

- Energy needs are relatively lower

- Many women tolerate extended fasting better during this phase

- Can try extending to 14-16 hours if feeling good

Luteal phase (approximately days 15-28):

- Begins after ovulation, ends at menstruation

- Progesterone rises, energy needs increase

- Many women feel hungrier and have less tolerance for restriction

- Recommendation: Limit fasting to 12-13 hours

- Priority: Adequate protein and energy. Don't fight hunger signals

Signs of Over-Restriction¶

Teach clients (and watch for these yourself) signs that fasting may be too aggressive:

Physical signs:

- Menstrual irregularities (missed periods, longer cycles)

- Hair loss or thinning

- Feeling cold when others are comfortable

- Persistent fatigue

- Sleep disruption (waking at night hungry)

Psychological signs:

- Excessive preoccupation with food or eating windows

- Anxiety around meal times or "breaking" the fast

- Rigid rules that create stress

- Social isolation to maintain fasting schedule

If clients report these signs, the answer is typically: back off—use shorter fasting windows, more food, and less restriction, because health is the goal, not fasting achievement.

Special Populations¶

Pregnancy: TRE is not recommended. Energy and nutrient needs are elevated; this is not the time for any form of restriction.

Breastfeeding: Caution is warranted because milk production requires significant energy, and if TRE is practiced at all, windows should be minimal (12 hours maximum) and adequate calories ensured.

Perimenopause: Highly individual. Some women do well with TRE; others find it exacerbates symptoms (sleep disruption, mood changes). Start conservative, adjust based on response.

Post-menopause: Generally well-tolerated. Without menstrual cycle considerations, post-menopausal women can experiment with TRE like anyone else, with attention to protein adequacy and overall well-being.

Practical Framing for Coaches¶

The goal is not to medicalize normal eating. Here's how to present these considerations:

Coaching in Practice: Menstrual Cycle Considerations¶

Client: "I noticed fasting is way harder right before my period. Is that normal?"

Coach: "Totally normal. Your energy needs actually change across your cycle. In the second half, after ovulation, your body needs more energy. That's why you feel hungrier—your body's signaling correctly."

Client: "So should I not fast during that time?"

Coach: "Don't fight your body. Limit fasting to 12-13 hours during the luteal phase, and eat when you're hungry. If you want to experiment with longer windows, the first half of your cycle—before ovulation—is when most women tolerate it better."

Coaching in Practice: For Coaches Working With Female Clients¶

Client: (reports missed periods, fatigue, food preoccupation after starting fasting)

Coach: "Those are signals to back off, not push through. Your body is telling you the restriction is too much. Let's shorten your eating window, make sure you're eating enough, and see how you feel in a few weeks. If your periods don't return, that's worth mentioning to your doctor."

Key principle: When in doubt, shorter fasting windows and adequate calories are safer choices for female clients.

Energy Availability: The Key Metric¶

For women, especially active women, energy availability may matter more than fasting duration. Energy availability = (Energy intake - Exercise energy expenditure) / Fat-free mass.

Research suggests ~45 kcal/kg fat-free mass per day supports menstrual function and athletic performance (Holtzman & Ackerman, 2021).

Translation for coaches: Fasting protocols that significantly reduce caloric intake and are combined with exercise may push energy availability too low, even if the fasting window itself seems moderate.

[CHONK: Coaching Metabolic Health]

Coaching Metabolic Health: Scope and Practice¶

Metabolic health sits at the edge of coaching scope. Some aspects are clearly within bounds; others require medical collaboration. This section clarifies boundaries and provides practical coaching approaches.

Scope of Practice: Clear Boundaries¶

Coaches CAN:

- Educate about metabolic health concepts (what you've learned in this chapter)

- Coach eating timing and meal composition strategies

- Guide TRE implementation for healthy clients

- Help clients notice patterns in energy, hunger, and response to foods

- Ask questions about energy levels, hunger patterns, and eating habits

- Support clients in implementing recommendations from their healthcare provider

Coaches CANNOT:

- Diagnose insulin resistance, prediabetes, diabetes, or metabolic syndrome

- Interpret lab values (HbA1c, fasting glucose, lipid panels) diagnostically

- Recommend TRE for clients with eating disorder history without medical clearance

- Treat metabolic disorders

- Adjust medication timing or dosage

- Use CGM data to make clinical assessments

The Metabolic Health Decision Tree¶

Use this framework when metabolic concerns arise:

Client mentions metabolic concerns or blood sugar issues

↓

Does client have a diagnosed condition?

(diabetes, prediabetes, PCOS)

↓

┌───────YES──────┴────────NO──────────┐

↓ ↓

Is client working with Are there warning signs?

a medical provider? (see list below)

↓ ↓

┌──YES────┴───NO────┐ ┌────YES───┴────NO────┐

↓ ↓ ↓ ↓

Support their Refer to Refer to OK to coach

medical plan medical medical general

(within scope) provider provider strategies

Warning signs requiring referral:

- HbA1c >5.7% (prediabetes threshold. HbA1c measures average blood sugar over 2-3 months)

- Fasting glucose consistently >100 mg/dL

- Client reports "blood sugar crashes" or severe symptoms

- Signs of metabolic syndrome (multiple markers. See earlier table)

- Significant unexplained weight changes

- Client uses blood sugar-affecting medications

- History of eating disorders (needs clearance before any fasting approach)

Assessment Approaches (Within Scope)¶

You can gather useful information through conversation:

Questions about energy patterns:

- "How does your energy feel throughout the day?"

- "Do you feel like you need to eat every few hours or you crash?"

- "How do you feel if you miss a meal?"

- "Do you wake up at night hungry?"

Questions about eating patterns:

- "Walk me through a typical day of eating."

- "When do you eat your first and last food of the day?"

- "Do you snack frequently? What prompts that?"

- "How do you feel after different types of meals?"

Observations (not diagnoses):

- Client reports energy crashes → may benefit from blood sugar strategies

- Client eats most calories at dinner → could try earlier eating

- Client snacks constantly → may benefit from more satisfying meals

- Client reports carb cravings → ensure adequate protein and regular meals first

Building Sustainable Patterns¶

The coaching approach for metabolic health follows the same principles as all behavior change:

Start with fundamentals:

Before any timing optimization, ensure:

- Adequate protein at meals (Chapter 2.7)

- Sufficient vegetables and fiber

- Minimized ultra-processed foods

- Regular meals (not constant snacking, not skipping meals)

Add structure, not rigidity:

- Consistent meal times (rough schedule, not minute-perfect)

- Natural overnight fasting (12 hours is fine)

- Post-meal movement when practical

Progress based on response:

- If fundamentals are solid and client is interested, try extending overnight fast

- Monitor how the client feels, not just numbers

- Adjust based on feedback (energy, mood, sleep, hunger)

Avoiding Orthorexia and Restriction Anxiety¶

Orthorexia is an unhealthy obsession with "healthy" eating. Metabolic health interventions can trigger this in susceptible clients.

Watch for:

- Rigid rules that create stress ("I can't eat until exactly noon")

- Social isolation to maintain eating patterns

- Anxiety if eating window is "broken"

- Escalating restriction ("16 hours isn't enough, I need 20")

- Food as the primary focus of life

- Perfectionism about blood sugar numbers

Your response:

- Validate the interest in health while questioning the intensity

- Emphasize flexibility and sustainability over optimization

- Remind that occasional variations don't matter

- If concerning, refer for psychological support

Coaching in Practice: When TRE Creates Stress¶

Client: "I broke my fast early yesterday and I felt terrible about it all day."

Coach: "Can I share an observation? You seem more stressed about your eating window than you were before we started this. If this approach is making you think about food more, not less, it's not working."

Client: "But I want to get the longevity benefits..."

Coach: "Health includes your relationship with food, not just metabolic markers. What if we stepped back to something simpler? Finish dinner by 7pm, eat when you're hungry in the morning, focus on food quality instead of timing perfection. The anxiety costs more than the benefits."

Case Study: Client Wanting to "Optimize Metabolism"¶

Sarah, 42, comes to you wanting to "optimize her metabolism." She's read about intermittent fasting, metabolic flexibility, and glucose optimization. She has a CGM and tracks everything.

Assessment reveals:

- Already eating adequate protein (good)

- Exercises 4x/week including strength training (good)

- Sleeps 6 hours/night (concern)

- Very anxious about glucose "spikes" on CGM

- Has restricted eating window to 6 hours daily

- Feeling tired and irritable

The coaching approach:

Step 1: Identify the real issue

Sarah's fatigue and irritability may be from under-eating (6-hour window makes adequate nutrition hard) and poor sleep, not suboptimal metabolism.

Step 2: Redirect focus

"Sarah, I appreciate how dialed-in you are, but I'm wondering if we're optimizing the wrong things. Your sleep at 6 hours is probably affecting your metabolism more than your eating window. And I notice you're pretty stressed about your CGM readings. That stress itself affects blood sugar. What if we simplified: extend your eating window back to 8-10 hours so you can easily hit protein targets, prioritize getting to 7-8 hours of sleep, and put the CGM away for a few weeks? Let's see how you feel."

Step 3: Monitor response

- Did energy improve?

- Did anxiety decrease?

- Is she enjoying food more?

[CHONK: Deep Health Integration]

[CHONK: Deep Health Integration]

Deep Health Integration¶

Metabolic health touches every dimension of Deep Health. Here's how:

Physical¶

This is the primary dimension for this chapter. Blood sugar regulation, metabolic flexibility, body composition, and energy production all fall here. The interventions we've discussed—post-meal walks, meal composition, reasonable TRE—directly support physical metabolic function.

Mental¶

Brain function depends on glucose regulation. The brain uses about 20% of your glucose, and it's sensitive to both too-high and too-low blood sugar.

- Stable blood sugar → better focus, clearer thinking

- Wild glucose swings → brain fog, difficulty concentrating

- Long-term glycemic control → reduced cognitive decline risk

The MIND diet connection from Chapter 2.7 applies here too: what and when you eat affects brain health.

Emotional¶

Your relationship with food is part of health. This is where metabolic optimization can go wrong.

If metabolic interventions create:

- Anxiety about eating windows

- Fear of "bad" foods

- Guilt about glucose spikes

- Rigid rules that remove eating enjoyment

...then they're harming emotional health even if "improving" metabolic markers. Balance matters.

Social¶

Eating is fundamentally social. Rigid meal timing can isolate people:

- Can't join friends for late dinner

- Anxiety about eating at "wrong" times at social events

- Family meals disrupted by individual eating windows

Coach flexibility; occasional deviation from patterns for social eating is not just acceptable—it's healthy. "I skip the fasting window on Sundays for family brunch" is a reasonable approach.

Environmental¶

Eating aligned with circadian rhythms connects to environmental health. We're biologically designed to eat during daylight and rest at night. Modern life (late-night eating, shift work, artificial light) disrupts this alignment.

Simple interventions:

- Finish eating earlier in the evening

- Eat larger meals earlier in the day when possible

- Align eating with natural light cycles

Existential¶

What kind of relationship with food timing do you want?

Help clients reflect:

- Is this approach sustainable for life, or a short-term experiment?

- Does this align with how they want to live?

- Is the pursuit of metabolic optimization enhancing or diminishing their life?

Some clients genuinely enjoy structure and tracking, while others find it burdensome, and both responses are valid. The goal is helping clients find approaches that serve their larger life goals.

Study Guide Questions¶

These questions help you review the chapter and prepare for the exam. They're optional but recommended.

-

What is metabolic flexibility, and why does it decline with age? What intervention is most effective for improving it?

-

Describe three evidence-based strategies for managing postprandial (after-meal) blood sugar, and explain the mechanism behind each.

-

What does the evidence actually show about time-restricted eating and weight loss? What's the significance of the NEJM trial comparing TRE + calorie restriction to calorie restriction alone?

-

Why do women need different considerations for fasting than men? What are the signs that a fasting approach may be too aggressive for a female client?

-

What can coaches do regarding metabolic health, and what must be referred to medical providers? Use specific examples.

-

How would you respond to a client who says: "I heard that fasting activates autophagy and reverses aging. Should I do a 24-hour fast every week?"

Self-reflection questions:

-

Notice your own blood sugar patterns: When do you feel most energetic? When do you crash? What patterns do you notice between what you eat and how you feel 2-3 hours later?

-

If you were to try a time-restricted eating approach, what eating window would realistically fit your life? What would make it sustainable vs. unsustainable?

Deep Dives¶

Want to go deeper? These supplemental articles explore key topics from this chapter in more detail.

- CGM Interpretation Guide: For coaches working with clients using CGMs

- Fasting Research Deep Dive — Animal vs. human evidence comparison

References¶

-

Effects of time-restricted eating on body composition and metabolic parameters in overweight and obese women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Effects of time-restricted eating on body composition and metabolic parameters in overweight and obese women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Nutrition; 2025. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12479299/

-

Not specified. The Effect of Time-Restricted Eating Combined with Exercise on Body Composition and Metabolic Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Advances in Nutrition; 2024. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11301358/

-

Not provided. Efficiency of time-restricted eating and energy restriction on anthropometrics and body composition in adults. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity; 2025. https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-025-01812-w

-

Liu D, Huang Y, Huang C, Yang S, Wei X, Zhang P, et al. Calorie Restriction with or without Time-Restricted Eating in Weight Loss. New England Journal of Medicine. 2022;386(16):1495-1504. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2114833

-

Li C, Xing C, Zhang J, Zhao H, Shi W, He B. Eight-hour time-restricted feeding improves endocrine and metabolic profiles in women with anovulatory polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2021;19(1). doi:10.1186/s12967-021-02817-2

-

Cienfuegos S, Corapi S, Gabel K, Ezpeleta M, Kalam F, Lin S, et al. Effect of Intermittent Fasting on Reproductive Hormone Levels in Females and Males: A Review of Human Trials. Nutrients. 2022;14(11):2343. doi:10.3390/nu14112343

-

Męczekalski B, Niwczyk O, Battipaglia C, Troia L, Kostrzak A, Bala G, et al. Neuroendocrine disturbances in women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea: an update and future directions. Endocrine. 2023;84(3):769-785. doi:10.1007/s12020-023-03619-w

-

Recommendations and Nutritional Considerations for Female Athletes: Health and Performance. Recommendations and Nutritional Considerations for Female Athletes: Health and Performance. Sports Medicine; 2021. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8566643/

-

Ranneh Y, Hamsho M, Shkorfu W, Terzi M, Fadel A. Effect of Intermittent Fasting on Anthropometric Measurements, Metabolic Profile, and Hormones in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2025;17(15):2436. doi:10.3390/nu17152436

-

Lovell DI, Stuelcken M, Eagles A. Exercise Testing for Metabolic Flexibility: Time for Protocol Standardization. Sports Medicine - Open. 2025;11(1). doi:10.1186/s40798-025-00825-w

-

Not specified. Age-related susceptibility to insulin resistance arises from a combination of CPT1B decline and lipid overload. BMC Biology; 2021. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8323306/

-

Impaired Metabolic Flexibility to High-Fat Overfeeding Predicts Future Weight Gain in Healthy Adults. Diabetes. 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6971489/

-

Unknown. After Dinner Rest a While, After Supper Walk a Mile? A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis on the Acute Postprandial Glycemic Response to Exercise. Sports Medicine; 2023. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10036272/

-

Kang J, Fardman BM, Ratamess NA, Faigenbaum AD, Bush JA. Efficacy of Postprandial Exercise in Mitigating Glycemic Responses in Individuals with Overweight, Obesity, and Type 2 Diabetes – A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. 2023. doi:10.20944/preprints202309.2173.v1

-

Brian MS, Chaudhry BA, D’Amelio M, Waite EE, Dennett JG, O’Neill DF, et al. Post-meal exercise under ecological conditions improves post-prandial glucose levels but not 24-hour glucose control. Journal of Sports Sciences. 2024;42(8):728-736. doi:10.1080/02640414.2024.2363688

-

N/A. Food order affects blood glucose and insulin levels in women with gestational diabetes. Frontiers in Nutrition; 2024. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11703717/

-

Imai S, Kajiyama S, Kitta K, Miyawaki T, Matsumoto S, Ozasa N, et al. Eating Vegetables First Regardless of Eating Speed Has a Significant Reducing Effect on Postprandial Blood Glucose and Insulin in Young Healthy Women: Randomized Controlled Cross-Over Study. Nutrients. 2023;15(5):1174. doi:10.3390/nu15051174

-

Unknown. A protein-rich meal provides beneficial glycemic responses. Frontiers in Nutrition; 2024. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2024.1395745/full

-

Unknown. Use of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Non-diabetic Individuals: A Systematic Review. Cureus; 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC12612783/

-

Unknown. Non-Invasive Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Patients Without Diabetes. Sensors; 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC11722592/

-

Not specified. Effects of Variability in Glycemic Indices on Longevity in Chinese Centenarians. Frontiers in Nutrition; 2022. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9307500/

-

unknown. Clinical biomarkers and associations with healthspan and lifespan. eBioMedicine; 2021. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8047464/

-

Nankervis SA, Mitchell JM, Charchar FJ, McGlynn MA, Lewandowski PA. Consumption of a low glycaemic index diet in late life extends lifespan of Balb/c mice with differential effects on DNA damage. Longevity & Healthspan. 2013;2(1). doi:10.1186/2046-2395-2-4

-

unknown. Effect of nine different exercise interventions on insulin sensitivity in diabetic patients. Frontiers in Endocrinology; 2025. https://doaj.org/article/3358fac92a5c41d99197c2badc9f083e

-

Unknown. Relationship of Ageing to Insulin Resistance and Atherosclerosis. Metabolites; 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC12471849/

-

Fujiwara T, Nakata R, Ono M, Mieda M, Ando H, Daikoku T, et al. Time Restriction of Food Intake During the Circadian Cycle Is a Possible Regulator of Reproductive Function in Postadolescent Female Rats. Current Developments in Nutrition. 2019;3(4):nzy093. doi:10.1093/cdn/nzy093