Unit 2: Core Interventions—The Protocol¶

Chapter 2.14: Environmental Health¶

[CHONK: 1-Minute Summary]

The bottom line on environmental health¶

Here's what you need to know about environmental health and longevity:

The fundamentals matter most. Sleep, exercise, nutrition, and social connection deliver the vast majority of health benefits. Environmental optimization is extra credit, meaningful only after the basics are solid.

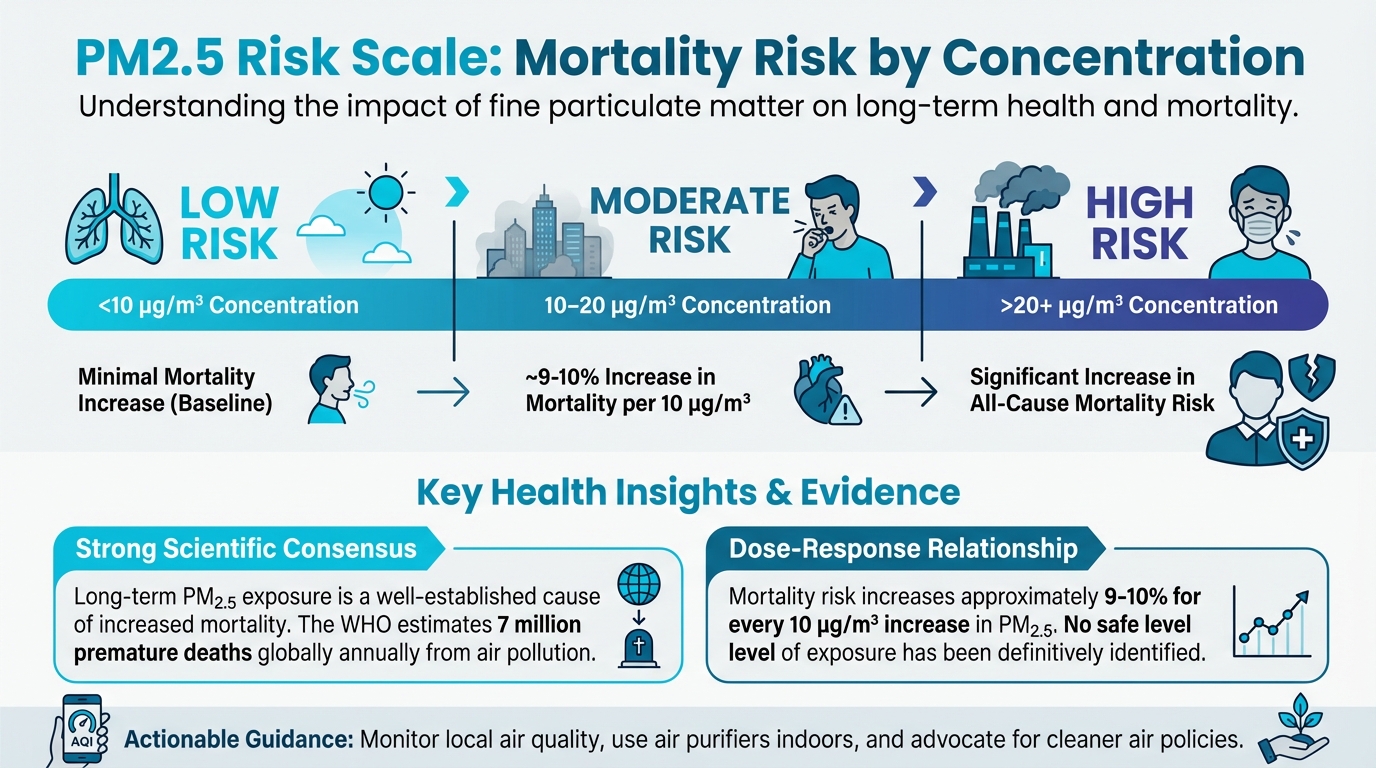

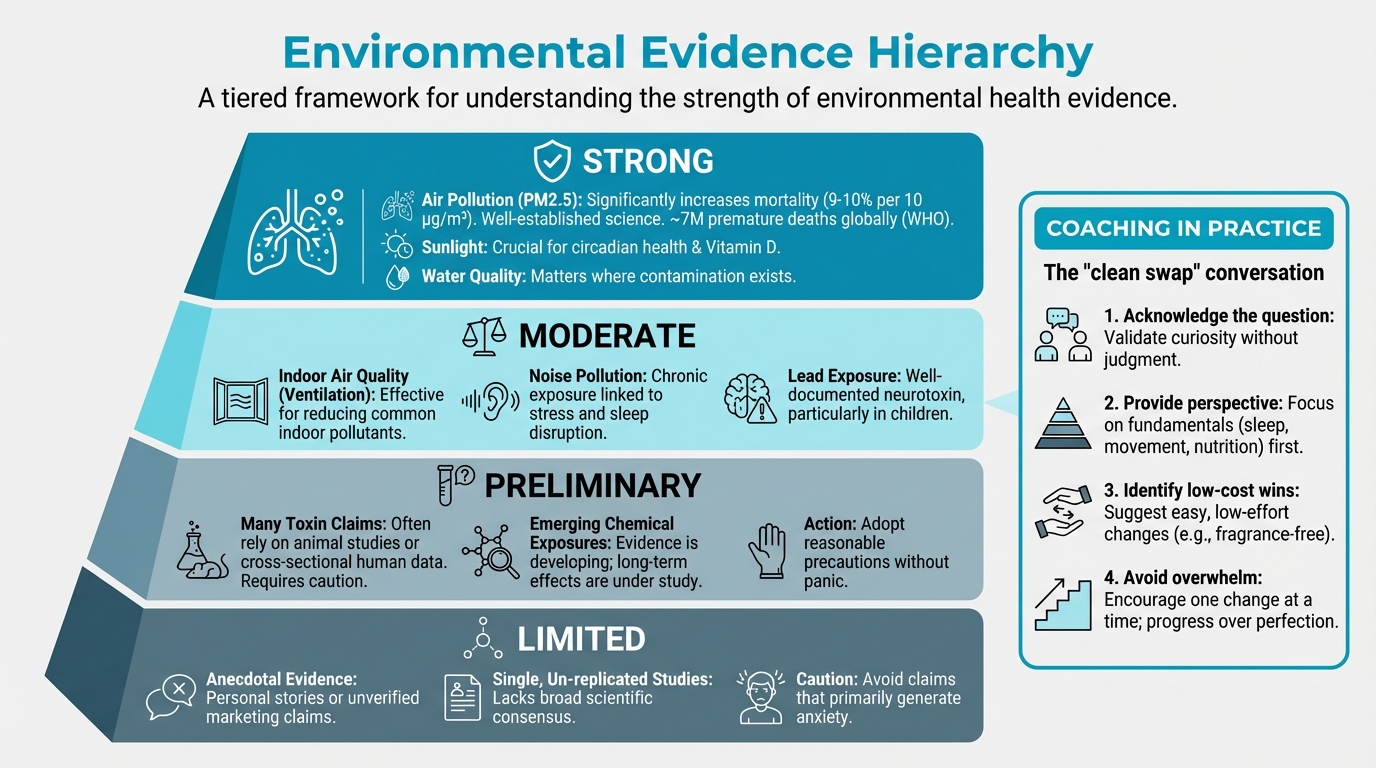

Some environmental evidence is strong. Air pollution significantly increases mortality risk (~9-10% per 10 µg/m³ PM2.5), and this is well-established science. Water quality matters where contamination exists, and sunlight is important for circadian health and vitamin D.

Figure: Mortality risk by concentration

Figure: Strong → Moderate → Preliminary → Limited

Much environmental evidence is preliminary. Many toxin claims, while concerning, rely on animal studies or cross-sectional human data. We should act on reasonable precautions without panic.

Progress over perfection. You don't need to overhaul your entire life. Small, low-cost changes (ventilation, avoiding heated plastic, water filtration if needed) provide most of the benefit. Expensive "clean living" products are rarely necessary.

Your job as a coach: Help clients make informed, proportionate decisions without creating anxiety or implying they're "poisoning themselves" by living normally, and focus on the big wins and ignore the noise.

[CHONK: The Environmental Dimension of Health]

Why environment matters for longevity¶

Your environment shapes your health in ways you may not notice. The air you breathe, the water you drink, the products you use, and the spaces you inhabit all contribute to your body's total load, the cumulative exposures it processes daily.

But here's the perspective you need: environmental factors are real, but they're not the primary drivers of longevity for most people.

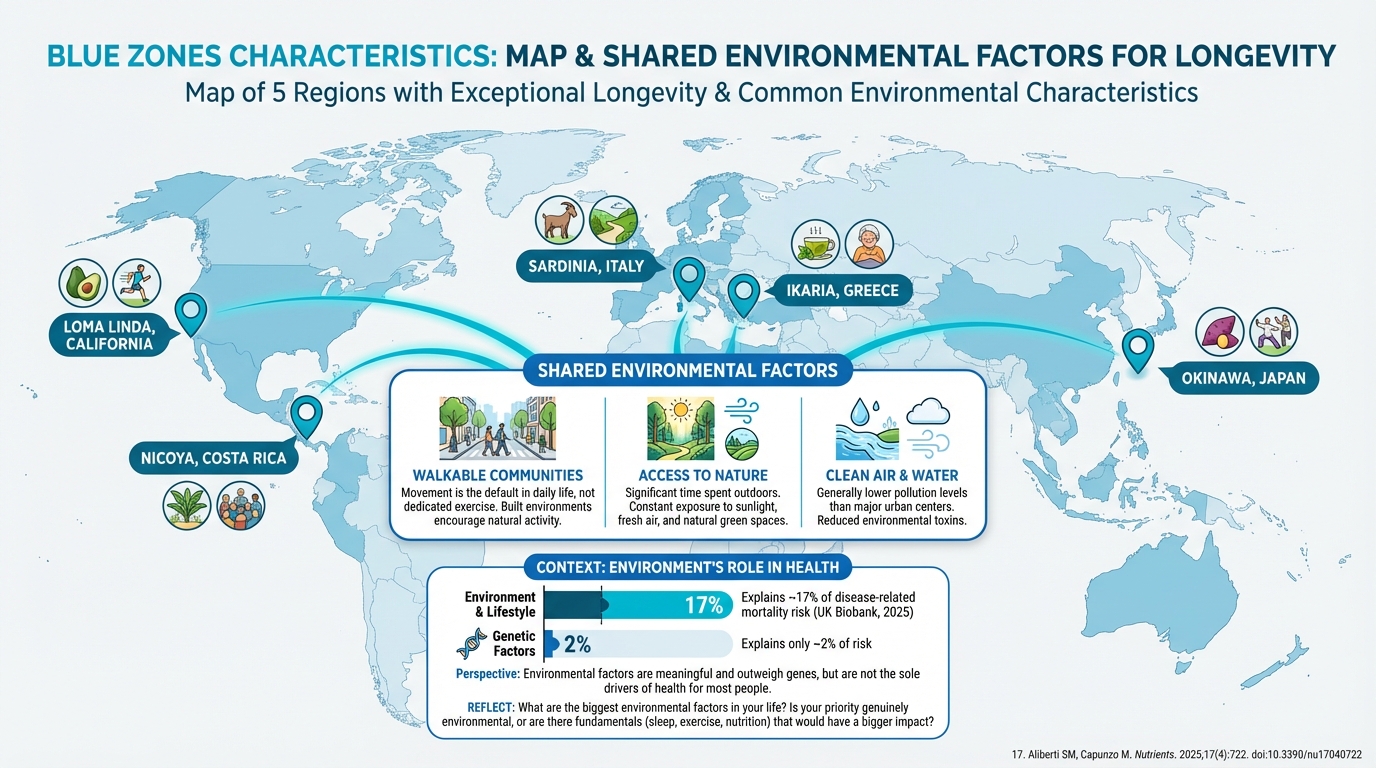

A 2025 analysis of nearly 490,000 participants in the UK Biobank found that environmental and lifestyle factors explained about 17% of disease-related mortality risk, while genetic factors explained only about 2%. That's meaningful. Environment matters more than genes. But it also means that 17% is distributed across many environmental and lifestyle factors. No single environmental exposure is likely to be your biggest health lever.

The hierarchy of health interventions¶

The interventions with the strongest longevity evidence are:

- Exercise (40% mortality reduction with combined training)

- Not smoking (single largest modifiable risk factor)

- Sleep quality (7-9 hours consistently)

- Nutrition (adequate protein, vegetables, minimal ultra-processed foods)

- Social connection (50% higher survival with strong relationships)

- Stress management (chronic stress accelerates aging)

Environmental optimization sits below these fundamentals. A client obsessing over PFAS in their water while sleeping 5 hours a night is, frankly, majoring in the minor.

Where environment genuinely matters¶

Certain environmental exposures have solid evidence for health impact:

Air pollution (strong evidence): Long-term exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) increases all-cause mortality by approximately 9-10% per 10 µg/m³ increase. The WHO estimates around 7 million premature deaths globally each year from air pollution (ambient and household combined). This is one of the best-established environmental health relationships we have.

Water contamination (variable by location): In communities with contaminated water supplies, drinking water can be a significant exposure source for PFAS, heavy metals, and other contaminants. This varies enormously by location. Many public water systems are excellent; some have documented problems.

Sunlight (strong evidence): Adequate light exposure is essential for vitamin D synthesis, circadian rhythm regulation, and mental health. Most people need 20+ minutes of direct sunlight daily.

Built environment: Walkable, green neighborhoods are associated with better health outcomes: lower mortality, lower cardiovascular risk, better mental health. Access to nature matters. A meta-analysis of nine cohort studies (~8.3 million participants) found that higher residential greenness within 500 meters is associated with approximately 4% lower all-cause mortality per 0.1-unit increase in vegetation index.

Blue Zones: environment in action¶

The Blue Zones—regions with exceptional longevity like Okinawa (Japan), Sardinia (Italy), Nicoya (Costa Rica), Ikaria (Greece), and Loma Linda (California)—aren't just about diet. They share common environmental characteristics:

Figure: 5 regions with common factors

Walkable communities: People in these regions walk as part of daily life, not as dedicated exercise. Their built environments make movement the default.

Access to nature: Blue Zone residents spend significant time outdoors, exposed to sunlight, fresh air, and natural spaces.

Clean air and water: These regions generally have lower pollution levels than major urban centers.

Social environments: The physical spaces support social connection: plazas, markets, community gathering places.

The point isn't that you need to move to Sardinia. It's that environment shapes behavior. When your surroundings make healthy choices easy—walking instead of driving, spending time outdoors, connecting with neighbors—health happens naturally. Part of environmental health is designing your personal environment to support the life you want.

What this means for your client¶

When coaching environmental health:

- Start with fundamentals: If sleep, exercise, and nutrition aren't solid, those are the priority

- Assess their specific situation: Do they live near a pollution source? Is their water supply known to have issues? What's their actual exposure profile?

- Avoid creating anxiety: Most people in developed countries are not being "poisoned" by their environment. They're facing the same modest exposures as everyone else

- Focus on accessible wins: The changes that matter most are often free or low-cost

[CHONK: Reducing Toxic Exposures]

Understanding toxic exposures¶

The term "toxic burden" refers to the cumulative load of environmental chemicals your body encounters. These include:

- PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances): Synthetic chemicals used in non-stick coatings, water-resistant fabrics, and food packaging

- BPA/bisphenols: Found in some plastics and can linings

- Phthalates: Used in plastics and fragrances

- Heavy metals: Lead, cadmium, arsenic from various sources

Before we discuss reducing exposures, let's be honest about the evidence.

What the evidence actually shows¶

PFAS: A 2024 umbrella review synthesizing 157 meta-analyses found high-certainty evidence that certain PFAS are associated with lower birth weight and reduced vaccine antibody responses. Moderate-certainty evidence links them to impacts on infant BMI and some pregnancy outcomes. However, many other associations (cardiovascular disease, infertility, gestational hypertension) remain low or very low certainty. The dose-response at typical exposure levels in the general population is less clear than headlines suggest.

BPA and bisphenols: Meta-analyses associate BPA exposure with obesity (pooled odds ratio approximately 1.4-3.5 for highest vs. lowest exposure), type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular effects. However, much of this evidence comes from cross-sectional studies, which can show association but not prove causation. Mechanistic pathways are plausible (BPA can interfere with estrogen receptors), but the magnitude of effect at typical exposures remains debated.

Phthalates: Human studies link exposure to hypertension, obesity, and diabetes. These are endocrine-active chemicals, and exposure is widespread. Evidence suggests harmful effects at lower doses than previously thought, though most studies are observational.

Heavy metals (lead, cadmium, arsenic): This is where evidence is strongest. Meta-analyses across 42 cohort studies show clear associations between cadmium and lead exposures and higher all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality. Arsenic exposure is linked to chronic kidney disease and cancer risk. Heavy metals are established health hazards with clear dose-response relationships.

Practical toxin reduction strategies¶

Given this evidence picture, here are proportionate, evidence-informed strategies:

Food storage and cookware

The concern: Heating plastic can increase chemical leaching. Non-stick coatings contain PFAS or related compounds. When plastic is heated, it can release chemicals at higher rates than when at room temperature.

What to do:

- Avoid microwaving food in plastic containers. Transfer to glass or ceramic

- Don't put hot food directly into plastic containers. Let it cool first

- Replace worn non-stick cookware (scratched, peeling) with stainless steel, cast iron, or ceramic

- Use glass or stainless steel containers for food storage when practical

- Avoid plastic water bottles that sit in hot cars

Cost: Free to low (replacing cookware over time as items wear out)

What to know: Cast iron is inexpensive and lasts decades, and stainless steel is durable and versatile. These aren't premium options; they're practical ones, and you don't need to replace everything at once. As non-stick items wear out, replace them with alternatives.

Personal care products

The concern: Parabens, phthalates, and synthetic fragrances may act as endocrine disruptors, though human evidence at typical exposures is mixed.

What to do:

- Check products using the EWG Skin Deep database (ewg.org/skindeep)

- Consider fragrance-free options for products used daily

- Focus on products that stay on skin (lotions, deodorants) rather than rinse-off products

Cost: Variable; many drugstore brands offer fragrance-free options at similar prices

Produce selection

The concern: Pesticide residues on some produce.

What to do:

- If budget allows, prioritize organic for the "dirty dozen" (strawberries, spinach, etc.). EWG updates this list annually

- Wash all produce thoroughly regardless of organic status

- Don't let perfect be the enemy of good: conventional produce is far better than no produce

Cost: Variable (organic typically 20-30% more expensive)

What to know: Evidence that organic produce leads to better health outcomes is limited. Pesticide reduction is real, but whether this translates to meaningful health benefits at typical exposure levels is unclear. A client who eats conventional vegetables daily is far better off than one who eats organic vegetables occasionally because of cost. Don't let organic be the enemy of adequate produce intake. Eating more vegetables—organic or conventional—is what matters most.

Cleaning products and household chemicals

The concern: Some cleaning products contain harsh chemicals; fragranced products may contain undisclosed ingredients.

What to do:

- Use ventilation when cleaning (open windows, run fans)

- Choose unscented or naturally-scented cleaning products when available

- Avoid mixing cleaning products (especially bleach and ammonia)

- Store chemicals properly and away from living spaces

Cost: Often free or similar (many unscented products cost the same as scented versions)

What to know: The biggest risk from cleaning products is usually direct exposure (inhalation during use, skin contact) rather than trace residues. Good ventilation during use matters more than the specific product. Basic soap and water clean effectively for most household needs.

Evidence vs. fear: keeping perspective¶

Here's where we need to be careful. The wellness industry has built a massive business on fear of toxins. You've seen the messaging: "Your products are poisoning you," "Detox your home," "Everything causes cancer."

This is not our approach.

The reality:

- Humans have always been exposed to environmental chemicals (natural and synthetic)

- Bodies have detoxification systems that handle most normal exposures

- The dose makes the poison. Presence of a chemical doesn't mean harm

- Most toxin claims extrapolate from high-dose animal studies or test-tube research to everyday human exposures

Our job is to help clients make reasonable risk-reduction choices without creating paralysis, anxiety, or financial strain.

Coaching in Practice: "Should I Be Worried About Toxins?"¶

Client: "I've been reading about all the chemicals in our food and products. Should I be switching to all-organic and getting rid of my plastic containers?"

Coach: "It makes sense you're curious about this. There's a lot of information out there—some of it helpful and some of it anxiety-inducing. Can I give you some perspective?"

Client: "Please. I'm feeling overwhelmed."

Coach: "The fundamentals—sleep, movement, nutrition, stress management—have much stronger evidence for health impact than most environmental changes. If those aren't solid, that's where I'd focus first. How are those going for you?"

Client: "Sleep could be better. But shouldn't I also be worried about chemicals?"

Coach: "There are some easy changes that make sense. Not microwaving food in plastic, choosing fragrance-free products when you can—those are low-effort and don't cost extra. But I wouldn't try to overhaul everything at once."

Client: "So I don't need to throw out all my plastic and go fully organic?"

Coach: "Not at all. Pick one thing to change, live with it, and see how it feels. Progress over perfection. And honestly? Improving your sleep will probably do more for your health than switching to organic vegetables. Let's focus on the big levers first."

[CHONK: Air and Water Quality]

Air quality: what you can control¶

Air quality is one area where the evidence is genuinely strong. Let's separate what we know from what we can do about it.

Outdoor air pollution¶

The data is clear: long-term exposure to PM2.5 (fine particulate matter smaller than 2.5 micrometers) increases all-cause mortality. A 2024 WHO-commissioned meta-analysis of 106 cohort studies found approximately 9.5% higher all-cause mortality per 10 µg/m³ increase in annual PM2.5 exposure. Cardiovascular and respiratory deaths show similar elevations.

What's notable: this relationship persists even at low concentrations. The WHO's 2021 Air Quality Guidelines reduced the recommended annual PM2.5 level to just 5 µg/m³, lower than most urban areas achieve.

What you can't easily control:

- Outdoor air quality in your neighborhood

- Wildfire smoke

- Traffic pollution

What you can do:

- Check air quality index (AQI) on high-pollution days

- Reduce outdoor exercise when AQI is unhealthy

- Consider location when making major life decisions (moving, buying a home)

Indoor air quality¶

Here's something many people don't realize: people spend approximately 90% of their time indoors, and indoor air can be more polluted than outdoor air for certain contaminants.

Indoor pollution sources include:

- Cooking (especially gas stoves)

- Cleaning products

- Off-gassing from furniture and building materials (VOCs)

- Outdoor pollution that enters the home

- Mold and allergens

CO2 and cognitive performance: Here's something particularly relevant for coaches working with office-based clients. Carbon dioxide (CO2) levels in enclosed spaces directly affect cognitive function. Most people have no idea.

Outdoor CO2 is approximately 420 ppm (parts per million). In a poorly ventilated office, meeting room, or home office, levels can climb to 1,000-2,500 ppm or higher. Research shows measurable cognitive effects at these common indoor levels:

- At ~950 ppm: cognitive function scores decline approximately 15%

- At ~1,400 ppm: decline can reach up to 50%, particularly affecting strategic thinking, decision-making, and crisis response

- At 1,000-2,000 ppm: common symptoms include fatigue, poor concentration, and headaches

This isn't about air pollution or toxins. It's basic physiology. When CO2 levels rise, your brain gets less efficient at complex thinking. That afternoon slump in a stuffy conference room? It's real, and it's partly CO2.

The good news: this is entirely fixable.

Solutions:

- Free: Open a window. Ventilation is remarkably effective. Even cracking a window can dramatically reduce CO2 buildup

- Free: Take breaks in well-ventilated areas, especially during long meetings

- Free: Step outside briefly every hour or two

- Low-cost ($100-150): CO2 monitors let you see exactly what's happening in your workspace and know when to ventilate

- Workplace advocacy: If your office is consistently stuffy, this is worth raising. It affects everyone's productivity

For clients who work from home, this is even more controllable. For those in office buildings with sealed windows, CO2 monitors can at least tell them when to take a break.

HEPA filtration: The evidence for HEPA air filtration is modest but positive. A meta-analysis of 14 randomized trials found that HEPA air purifiers produced small but statistically significant reductions in blood pressure, with the largest trial (200 participants, 1 year) showing approximately 7.7 mmHg systolic blood pressure reduction. Evidence quality is rated "very low" due to small studies and risk of bias, but the direction of effect is consistent.

What to do:

- Free: Open windows when outdoor air quality is good (ventilation is powerful)

- Free: Run exhaust fans when cooking

- Free: Avoid idling cars in attached garages

- Low-cost ($20-50): Check local AQI regularly and adjust activities accordingly

- Moderate ($100-300): HEPA air purifier in bedroom (where you spend 8 hours)

- Higher ($300+): HEPA filters for main living areas; consider whole-house filtration

Water quality¶

Water quality varies enormously by location. Many public water systems in developed countries deliver safe water that meets regulatory standards. Some have documented issues with PFAS, lead, or other contaminants.

How to assess your water:

- Look up your local water quality report (required for public systems in the US)

- Use the EWG Tap Water Database (ewg.org/tapwater) to check for detected contaminants

- If you have a private well, get it tested regularly

Filtration options by budget:

| Option | Cost | Effectiveness | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Let tap water sit uncovered | Free | Minimal (chlorine only) | Won't affect PFAS, metals |

| Pitcher filters | $25-50 + filters | Moderate (taste, some contaminants) | Limited effectiveness for PFAS |

| Faucet-mounted filters | $20-50 + filters | Moderate | Convenient; replace filters regularly |

| Under-sink carbon filters | $100-200 + filters | Good (many contaminants) | Activated carbon effective for many chemicals |

| Reverse osmosis (RO) | $200-500 + filters | Excellent (removes most contaminants) | Also removes minerals; requires maintenance |

Important caveat: Point-of-use water filters require maintenance. Studies show that poorly maintained filters can actually harbor bacteria and potentially increase gastrointestinal illness risk. Biofilm can grow inside filter housings and on cartridges if they're not replaced regularly. If you use a filter, change cartridges as recommended, typically every 2-6 months depending on the system.

Another consideration with reverse osmosis: RO systems remove most contaminants, but they also remove beneficial minerals. This is generally not a concern if you're eating a varied diet, but it's worth knowing. Some people add mineral drops to RO water or install remineralization filters.

For most people: If your local water meets standards and you have no specific concerns, a basic carbon filter is reasonable. It improves taste and removes chlorine and some contaminants. If your water has documented contamination (PFAS, lead), invest in more robust filtration (under-sink activated carbon or RO). If you have a private well, regular testing is essential. Wells aren't monitored like public systems.

The "check your situation" approach¶

Environmental interventions should be proportionate to actual exposure. This means:

- Check local data first: Look up your air quality index trends and water quality reports before buying anything

- Identify actual concerns: Is there a specific documented issue, or general anxiety?

- Match intervention to problem: HEPA filters help with PM2.5; they don't help with everything

- Avoid blanket solutions: "Everyone needs a whole-house filtration system" is not evidence-based advice

A client in a rural area with excellent air quality doesn't need a HEPA filter. A client in an urban area with documented air quality issues might benefit substantially. Context matters.

| Coaching in practice | |

|---|---|

| Budget-tiered air and water quality improvements | |

| Free/near-free: | |

| - Open windows for ventilation when AQI is good | |

| - Run exhaust fans when cooking | |

| - Check local water quality report | |

| - Stop microwaving food in plastic | |

| Low-cost ($0-50): | |

| - Basic water pitcher filter | |

| - Indoor plants (modest air quality benefits, significant well-being benefits) | |

| - Monitor AQI and adjust outdoor activities | |

| Moderate ($50-200): | |

| - HEPA air purifier for bedroom | |

| - CO2 monitor for home office/workspace | |

| - Under-sink water filter | |

| - Replace worn non-stick cookware | |

| Investment ($200+): | |

| - Whole-house HEPA or high-quality filters | |

| - Reverse osmosis water system | |

| - Professional air quality assessment | |

| Start at the top. Move down only as budget and priorities allow. |

[CHONK: Light and Circadian Health]

Sunlight: the forgotten essential¶

While much environmental health discussion focuses on avoiding harms, let's not overlook something your body needs: light.

Why sunlight matters¶

Sunlight exposure is essential for:

Vitamin D synthesis: Your skin produces vitamin D when exposed to UVB radiation. While supplements can provide vitamin D, sunlight offers additional benefits.

Circadian rhythm regulation: Morning light exposure is the most powerful signal for setting your body's internal clock. This affects sleep quality, hormone release, mood, and metabolic health.

Mood and mental health: Light exposure influences serotonin production and has documented effects on depression. Seasonal affective disorder is essentially a light deficiency condition.

Potentially other mechanisms: Emerging research suggests sunlight may trigger nitric oxide release, benefiting blood pressure, independent of vitamin D.

The protocol recommendation¶

The longevity protocol recommends 20+ minutes of direct sunlight daily.

How to achieve this:

- Morning sunlight within 30 minutes of waking is ideal for circadian entrainment

- Face toward the sun (you don't need direct eye exposure, ambient light works)

- Don't wear sunglasses for this morning exposure (glasses block the light signals to your circadian system)

- Avoid burning. The goal is light exposure, not tanning

For clients who work indoors:

- Take breaks outside

- Walk meetings when possible

- Eat lunch outdoors

- Position workspace near windows

Evening light and sleep¶

The flip side of morning light is evening darkness. Blue light from screens and bright lighting in the evening suppresses melatonin, the hormone that signals sleep readiness.

Practical approaches:

- Dim lights in the evening (especially overhead lights)

- Use "night shift" or similar settings on devices after sunset

- Consider blue-light-blocking glasses if screen use is unavoidable

- Keep the bedroom dark for sleep

This connects directly to Chapter 2.11 (Sleep Optimization). Circadian health is foundational.

| For DIY Learners |

|---|

| Applying this to yourself: Do a quick environmental audit of your home. Water: When did you last change your water filter? Have you ever tested your tap water? Air: When did you last changed your HVAC filter? Do you have any ventilation in your kitchen? Light: Are your evening lights too bright? These three—water, air, light—are the free-to-low-cost environmental improvements that matter most. Start there before worrying about exotic toxins. |

Light summary¶

Light is medicine. Unlike many environmental health topics where the goal is avoidance, with light the goal is intentional exposure:

| Time of Day | Recommendation | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Morning (first 30 min after waking) | Bright outdoor light, no sunglasses | Sets circadian clock, improves sleep quality |

| Midday | 20+ minutes outdoor exposure | Vitamin D, mood, general health |

| Evening | Dim lights, warm tones | Prepares body for sleep, supports melatonin |

| Night | Dark bedroom | Optimizes sleep quality and duration |

For clients who work indoors all day, this may require intentional planning: morning walks, outdoor lunch breaks, or even just standing near a window. The return on this investment is significant.

A brief note on EMF¶

The protocol mentions keeping phones away from the body and using airplane mode at night. Let's be clear about the evidence:

The evidence for health effects from typical EMF exposure (cell phones, WiFi) is limited. While some people report sensitivity, controlled studies have not demonstrated consistent harm at typical exposure levels. Major scientific bodies have not found convincing evidence of health effects from low-level non-ionizing radiation.

Reasonable precautions:

- Keep phone in bag rather than pocket when practical

- Use airplane mode or keep phone away from bed while sleeping

- These are low-effort practices that cost nothing

What we don't recommend:

- Expensive "EMF shielding" products

- Anxiety about WiFi or standard household electronics

- Major lifestyle disruption based on unproven concerns

If a client is concerned about EMF, acknowledge their concern, provide the evidence honestly, and suggest the low-cost precautions above. Don't amplify unfounded fears, but don't dismiss their questions either.

[CHONK: Coaching Environmental Health]

[CHONK: Coaching Environmental Health]

Bringing it together: coaching environmental health¶

Now that we've covered the science, let's talk about practical coaching application.

Assessment: where to start¶

In Chapter 1.4, we covered environmental health assessment questions. Key areas to explore:

- Living environment: What's their home like? Urban, suburban, rural? Near pollution sources?

- Work environment: Indoor air quality? Access to natural light?

- Water source: Municipal, well, bottled? Any known contamination issues?

- Product use: Do they use many fragranced products? Cook with non-stick?

- Outdoor access: Do they get outside regularly? Access to green space?

Most importantly: Where in the hierarchy are they? If sleep is poor, exercise is minimal, and stress is high, that's where to focus; environmental optimization comes later.

Prioritization: the impact-effort matrix¶

Help clients think about changes in terms of impact and effort:

High impact, low effort (do these first):

- Not microwaving food in plastic

- Opening windows for ventilation

- Getting morning sunlight

- Checking local water quality

- Using exhaust fans when cooking

Moderate impact, moderate effort:

- HEPA filter for bedroom

- Water filtration if needed

- Replacing worn non-stick cookware

- Choosing fragrance-free products

Lower impact or higher effort (optional):

- Organic produce (budget-dependent)

- Whole-house filtration systems

- Comprehensive product audit

Budget considerations¶

Environmental health can become expensive fast if you follow every recommendation from wellness influencers. Be explicit with clients:

Free interventions matter most:

- Ventilation

- Sunlight

- Not heating plastic

- Reading labels

- Checking water quality reports

Low-cost interventions are reasonable:

- Basic water filter

- Replacing old plastic containers with glass (over time)

- Fragrance-free personal care (often same price)

Expensive interventions are optional:

- Whole-house filtration

- All-organic diet

- Professional environmental assessments

Tell clients: "You don't need to spend a lot of money to address environmental health. The most impactful changes are often free."

Avoiding "clean living" overwhelm¶

The wellness industry has created a culture of fear around environmental toxins. Social media amplifies this with dramatic claims about everyday products "poisoning" us. Some clients arrive already anxious about their environment.

Watch for these warning signs:

- Anxiety about every product and food choice

- Spending significant money on "clean" products they can't afford

- Feeling guilty about normal life choices

- Paralysis from too many things to "fix"

- Catastrophizing about past exposures ("I've been poisoning myself for years")

- Orthorexia-like patterns extending to products, not just food

- Environmental concerns crowding out other health behaviors

If you see this pattern, step back:

"I notice you're feeling overwhelmed by environmental concerns. Let's get some perspective. You're not being poisoned by living a normal life. Bodies are remarkably resilient. That's literally what they evolved to do. The fundamentals we've talked about matter far more than optimizing every product you use. Let's focus on the two or three changes that would have the biggest impact, and let go of the rest."

Help clients distinguish between:

- Reasonable precautions (not microwaving plastic, using ventilation): Low-effort, evidence-informed, no anxiety required

- Helpful if concerned (water filtration, HEPA): Targeted responses to specific situations

- Diminishing returns (organic everything, comprehensive product audits): Expensive, time-consuming, marginal benefit for most people

- Not evidence-based (expensive "detox" programs, EMF shielding products): Skip entirely

The "good enough" standard¶

Perfectionism is the enemy of sustainable health behavior for environmental health:

- You don't need zero exposure to anything

- You don't need the "cleanest" version of every product

- You don't need to audit your entire home

- You don't need to feel bad about past choices

"Good enough" means:

- Making a few evidence-based changes

- Not stressing about what you can't control

- Focusing energy on fundamentals

- Recognizing that the dose makes the poison. Trace exposures aren't emergencies

A client who makes three low-cost environmental improvements and sleeps well at night is healthier than one who obsesses over every potential toxin but lies awake anxious.

When to refer¶

Some situations warrant professional assessment:

- Known contamination in home (lead paint, mold)

- Occupational exposures

- Unexplained symptoms that might relate to environment

- Home built before 1978 with children (lead risk)

Refer to:

- Certified home inspectors for structural/contamination concerns

- Allergists for suspected environmental allergies

- Primary care for symptoms potentially related to exposures

- Environmental health professionals for workplace concerns

Practical resources for clients¶

When clients want to learn more, point them to evidence-based resources rather than fear-based wellness content:

For water quality:

- EWG Tap Water Database (ewg.org/tapwater): Look up local water quality

- Your local water utility's annual Consumer Confidence Report (required for public systems)

For product safety:

- EWG Skin Deep (ewg.org/skindeep): Database rating personal care products

- Consumer Reports: Independent product testing and reviews

For air quality:

- AirNow.gov: Real-time air quality index by location

- PurpleAir or similar: Hyperlocal air quality monitoring

For general information:

- EPA resources on household chemicals and safety

- CDC environmental health pages

What to avoid recommending:

- Individual "wellness influencer" advice (often not evidence-based)

- Products marketed with fear-based messaging

- Expensive testing panels without clear clinical indication

- "Detox" programs or products

Scope boundaries¶

Remember from Chapter 1.5: coaches educate and support, we don't diagnose or prescribe.

We can:

- Explain what the evidence shows

- Help clients assess their environment

- Suggest reasonable precautions

- Support behavior change around environmental health

- Refer when appropriate

We don't:

- Diagnose "toxic overload" or similar conditions

- Recommend specific medical interventions

- Advise on suspected poisoning or acute exposures

- Provide advice that should come from medical professionals

Coaching in Practice: "Should I Do a Detox?"¶

Client: "I've been reading about toxins in our environment and I'm worried. Should I be doing a detox? Getting my home tested?"

Coach: "It makes sense you're thinking about this. There's a lot of information out there, and some of it can feel scary. Let me share what the evidence actually shows, and then we can figure out what makes sense for you."

Client: "Okay. I just feel like I should be doing something."

Coach: "The biggest environmental health factors are actually pretty straightforward: air quality, water quality, and getting enough sunlight. The good news is that most of these are free or low-cost to address."

Client: "What about all the toxins in products and food?"

Coach: "Before we get into that, how are the fundamentals? Sleep, movement, nutrition? Those have much stronger evidence for health impact than most environmental changes. If those aren't solid, that's where I'd want to focus first."

Client: "My sleep's okay, I guess. Could be better."

Coach: "That's where I'd start. If you want to optimize your environment too, we can look at your specific situation—checking your local water quality, making sure you're getting morning sunlight, maybe adding a HEPA filter if you're in a high-pollution area. Small changes, big impact."

Client: "What about those detox programs I keep seeing advertised?"

Coach: "I'd steer you away from expensive 'detox' programs. Your body already has detoxification systems—liver, kidneys, skin—that work pretty well. What actually helps is supporting those systems with the basics: sleep, hydration, vegetables, movement. Progress over perfection. Let's pick one or two things that make sense for your situation and go from there."

[CHONK: Deep Health Integration]

Environmental health across the six dimensions¶

Environmental health is one of the six dimensions of Deep Health, but it connects to all the others.

Environmental (primary dimension)¶

This chapter IS about environmental health: being and feeling safe and secure, supported by your surroundings. Access to clean air, clean water, safe living spaces, and nature all fall here.

The environmental dimension also includes access to resources: healthcare, healthy food, exercise facilities, and social spaces. Environmental health isn't just about avoiding toxins; it's about having an environment that enables health.

Physical¶

Environmental factors directly affect physical health:

- Air pollution increases cardiovascular and respiratory disease

- Water contaminants can affect organ function

- Sunlight is necessary for vitamin D and circadian health

- Green space access correlates with better physical health metrics

Emotional¶

Environmental health affects emotional well-being in both directions:

- Feeling in control of your environment reduces anxiety

- BUT excessive worry about environmental toxins can create anxiety

- Access to nature has documented benefits for mood and stress

- Clean, organized living spaces support emotional regulation

Social¶

Environmental health has social dimensions:

- Household members share environmental exposures

- Family decisions about products, food, and home affect everyone

- Community environmental health (air quality, water quality) is shared

- Blue Zones research shows that social environments and physical environments interact

Mental¶

Environmental factors affect cognitive health:

- Air pollution is associated with cognitive decline

- Chronic worry about environmental exposures creates mental burden

- Clear, proportionate understanding of risks supports better decision-making

- Eliminating unnecessary anxiety frees mental space for what matters

Existential¶

For some clients, environmental stewardship is part of their purpose and values:

- Living in alignment with environmental values matters to them

- Making environmentally conscious choices is part of their identity

- This can be a source of meaning, or a source of perfectionism and guilt

The coaching opportunity¶

When working with environmental health, you're working with the whole person:

- Help clients find the balance between appropriate action and unnecessary anxiety

- Connect environmental choices to their values without creating perfectionism

- Recognize that environment shapes all other health behaviors

- Support clients in creating environments that make healthy choices easier

Environmental design for behavior change¶

One of the most powerful applications of environmental health thinking isn't about avoiding toxins, but about designing environments that support healthy behaviors:

Make healthy choices the default:

- Keep fruit visible on the counter; put less healthy options out of sight

- Store workout clothes where you'll see them

- Set up a meditation corner that invites use

- Arrange furniture to encourage movement (standing desk options, walking paths)

Remove friction from good behaviors:

- Pre-pack gym bag the night before

- Keep water bottles filled and accessible

- Create a pleasant sleep environment (cool, dark, comfortable)

- Have healthy snacks prepared and visible

Add friction to less helpful behaviors:

- Don't keep trigger foods in the house

- Put phone charger outside the bedroom

- Make unhealthy options inconvenient rather than forbidden

This is environmental health in the broadest sense, shaping your surroundings to make the life you want easier to live. It's often more impactful than worrying about trace chemicals.

Key takeaways¶

-

Fundamentals first: Sleep, exercise, nutrition, and social connection have stronger evidence for longevity than most environmental interventions. Don't let environmental optimization distract from the basics.

-

Air quality matters (strong evidence): PM2.5 exposure increases all-cause mortality by approximately 9-10% per 10 µg/m³. HEPA filtration shows modest benefits. Indoor air can be worse than outdoor. Ventilation helps.

-

Water quality varies by location: Check your local water quality. If contamination exists, filtration is worthwhile. If not, basic filters are sufficient. Maintain any filters you use.

-

Toxin evidence is mixed: Heavy metals have strong evidence for harm. PFAS and BPA associations exist but are often preliminary or from cross-sectional studies. Act on reasonable precautions without panic.

-

Low-cost wins matter most: Not microwaving plastic, ventilation, sunlight, and checking water quality are free. Don't assume expensive products are necessary.

-

Progress over perfection: Partial improvement is valuable. One or two changes are better than paralysis trying to do everything. Help clients avoid "clean living" overwhelm.

-

Sunlight is an intervention, not just risk: 20+ minutes daily supports vitamin D, circadian health, and mood. Morning light is particularly valuable.

[CHONK: Study Guide Questions]

Study Guide Questions¶

These questions can help you think through the material and prepare for the chapter exam. They're optional, but we recommend trying at least a few.

-

What is the approximate mortality increase associated with long-term PM2.5 exposure, and why is this considered "strong evidence"?

-

A client is anxious about PFAS in their environment. How would you describe the evidence, and what practical steps would you recommend?

-

What is the "hierarchy of interventions" concept, and why does it matter for coaching environmental health?

-

List three free or low-cost environmental health improvements and explain why they should be prioritized over expensive interventions.

-

How does environmental health connect to other Deep Health dimensions? Give two specific examples.

-

What are the warning signs that a client is experiencing "clean living" overwhelm, and how would you address it?

Self-reflection questions:

-

Look around your home: What's the air quality like? Is there adequate ventilation? When did you last change your air filter (if you have one)?

-

What's your water source? Have you ever tested it? What's one simple, low-cost improvement you could make to your living environment this month?

Deep Dives¶

Want to go deeper? These supplemental articles explore key topics from this chapter in more detail.

- Home Environment Audit: Detailed room-by-room assessment

- Water Quality Testing: How to interpret test results

References¶

-

Xing W, Sun J, Liu F, Shan L, Yin J, Li Y, et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and human health outcomes: An umbrella review of systematic reviews with meta-analyses of observational studies. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2024;472:134556. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.134556

-

Orellano P, Kasdagli M, Pérez Velasco R, Samoli E. Long-Term Exposure to Particulate Matter and Mortality: An Update of the WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Public Health. 2024;69. doi:10.3389/ijph.2024.1607683

-

World Health Organization. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide. 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240034228

-

Lin M, Lee C, Chuang Y, Shih C. Exposure to bisphenol A associated with multiple health-related outcomes in humans: An umbrella review of systematic reviews with meta-analyses. Environmental Research. 2023;237:116900. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2023.116900

-

Antoniou EE, Dekant W. Childhood PFAS exposure and immunotoxicity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of human studies. Systematic Reviews. 2024;13(1). doi:10.1186/s13643-024-02596-z

-

Lamas GA, Bhatnagar A, Jones MR, Mann KK, Nasir K, Tellez‐Plaza M, et al. Contaminant Metals as Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2023;12(13). doi:10.1161/jaha.123.029852

-

Xia X, Chan KH, Lam KBH, Qiu H, Li Z, Yim SHL, et al. Effectiveness of indoor air purification intervention in improving cardiovascular health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Science of The Total Environment. 2021;789:147882. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147882

-

Rojas-Rueda D, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Gascon M, Perez-Leon D, Mudu P. Green spaces and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. The Lancet Planetary Health. 2019;3(11):e469-e477. doi:10.1016/s2542-5196(19)30215-3

-

de Bont J, Jaganathan S, Dahlquist M, Persson Å, Stafoggia M, Ljungman P. Ambient air pollution and cardiovascular diseases: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2022;291(6):779-800. doi:10.1111/joim.13467

-

Ndlovu N, Nkeh-Chungag B. Impact of Indoor Air Pollutants on the Cardiovascular Health Outcomes of Older Adults: Systematic Review. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2024;Volume 19:1629-1639. doi:10.2147/cia.s480054

-

Wendel D, et al.. PFAS Information for Clinicians From ATSDR. ATSDR/CDC; 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC12087759/

-

Arp HPH, Gredelj A, Glüge J, Scheringer M, Cousins IT. The global threat from the irreversible accumulation of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). 2024. doi:10.26434/chemrxiv-2024-0djqt

-

Amen R, Ibrahim A, Shafqat W, Hassan EB. A Critical Review on PFAS Removal from Water: Removal Mechanism and Future Challenges. Sustainability. 2023;15(23):16173. doi:10.3390/su152316173

-

Liu J, Tian M, Qin H, Chen D, Mzava SM, Wang X, et al. Maternal bisphenols exposure and thyroid function in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 2024. doi:10.37766/inplasy2024.5.0129

-

Wu W, Li M, Liu A, Wu C, Li D, Deng Q, et al. Bisphenol A and the Risk of Obesity a Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis of the Epidemiological Evidence. Dose-Response. 2020;18(2):155932582091694. doi:10.1177/1559325820916949

-

Xu L, et al.. Associations between exposure to heavy metals and the risk of chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PubMed; 2021. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33960873/

-

Aliberti SM, Capunzo M. The Power of Environment: A Comprehensive Review of the Exposome’s Role in Healthy Aging, Longevity, and Preventive Medicine—Lessons from Blue Zones and Cilento. Nutrients. 2025;17(4):722. doi:10.3390/nu17040722

-

Lai KY, Webster C, Gallacher JE, Sarkar C. Associations of Urban Built Environment with Cardiovascular Risks and Mortality: a Systematic Review. Journal of Urban Health. 2023;100(4):745-787. doi:10.1007/s11524-023-00764-5

-

Liu M, Meijer P, Lam TM, Timmermans EJ, Grobbee DE, Beulens JWJ, et al. The built environment and cardiovascular disease: an umbrella review and meta-meta-analysis. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2023;30(16):1801-1827. doi:10.1093/eurjpc/zwad241

-

Westenhöfer J, Nouri E, Reschke ML, Seebach F, Buchcik J. Walkability and urban built environments—a systematic review of health impact assessments (HIA). BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1). doi:10.1186/s12889-023-15394-4

-

Zhou J, Kang R, Bai X. A Meta-Analysis on the Influence of Age-Friendly Environments on Older Adults’ Physical and Mental Well-Being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(21):13813. doi:10.3390/ijerph192113813

-

European Commission CORDIS. Indoor air pollution: new EU research reveals higher risks than previously thought. 2023. https://cordis.europa.eu/article/id/95197-indoor-air-pollution-new-eu-research-reveals-higher-risks-than-previously-thought

-

Hutton G, et al.. Cost-effectiveness of water quality interventions for preventing diarrhoeal disease in developing countries. Journal of Water and Health; 2008. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17878570/

-

Salve HR, Nawaz H, Dey S, Krishnan A, Sharma P, Madan K. Effectiveness of household-level interventions for reducing the impact of air pollution on health outcomes – a systematic review. Frontiers in Environmental Health. 2024;3. doi:10.3389/fenvh.2024.1410966

-

Nussbaumer-Streit B, Mayr V, Dobrescu AI, Wagner G, Chapman A, Pfadenhauer LM, et al. Household interventions for secondary prevention of domestic lead exposure in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020;2020(10). doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006047.pub6

-

World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality, 4th Edition. 2017. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/254637