Unit 2: Core Interventions — The Protocol¶

Chapter 2.13: Recovery & Regeneration¶

1-Minute Summary¶

Recovery is when adaptation actually happens. All those workouts, all that effort are just stress, and without adequate recovery, training becomes breakdown rather than buildup.

This chapter covers recovery modalities beyond sleep: heat exposure (sauna), cold exposure, contrast therapy, and de-load strategies. But here's what we need to be upfront about: the evidence varies widely. Finnish sauna studies show compelling associations with reduced cardiovascular mortality and dementia risk, but they're observational, not randomized trials. Cold exposure research is mostly preliminary, with small studies and modest effects.

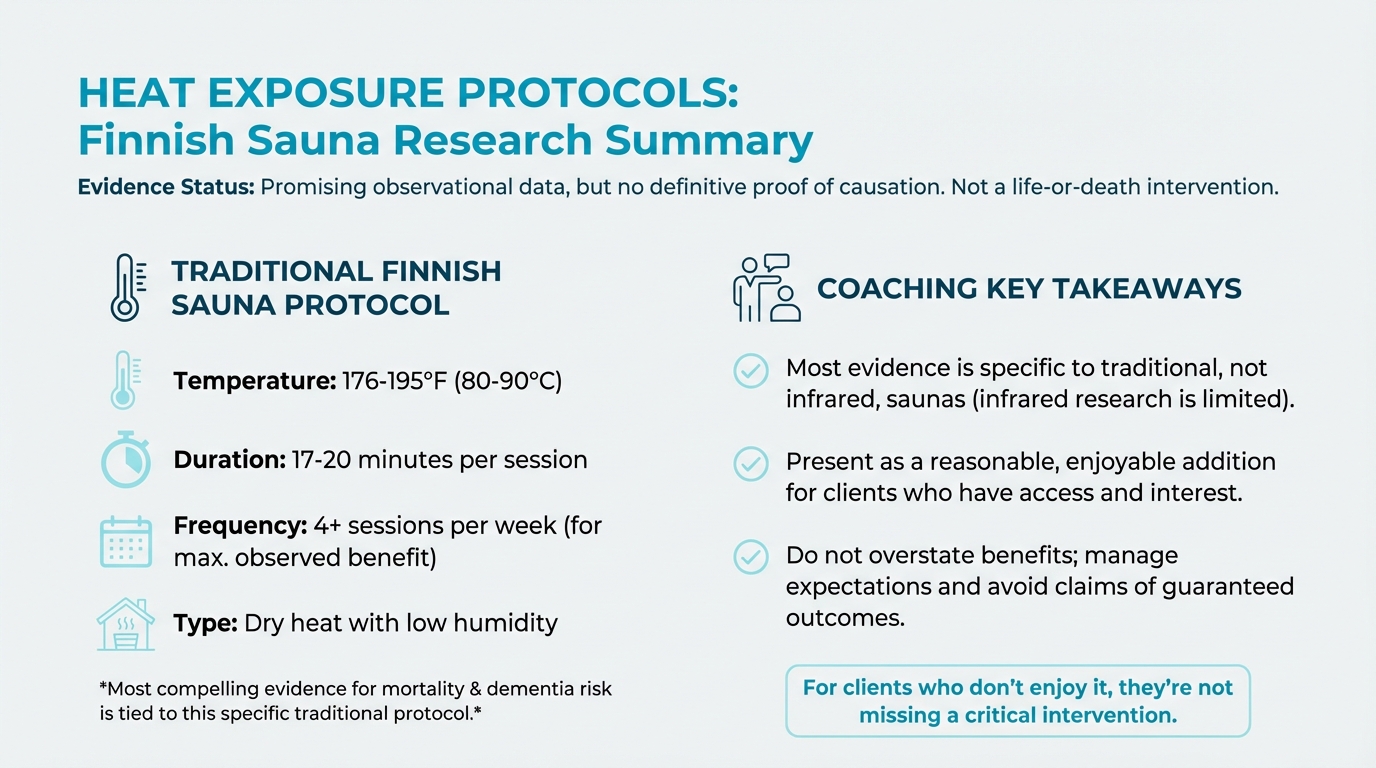

Figure: Finnish sauna research summary

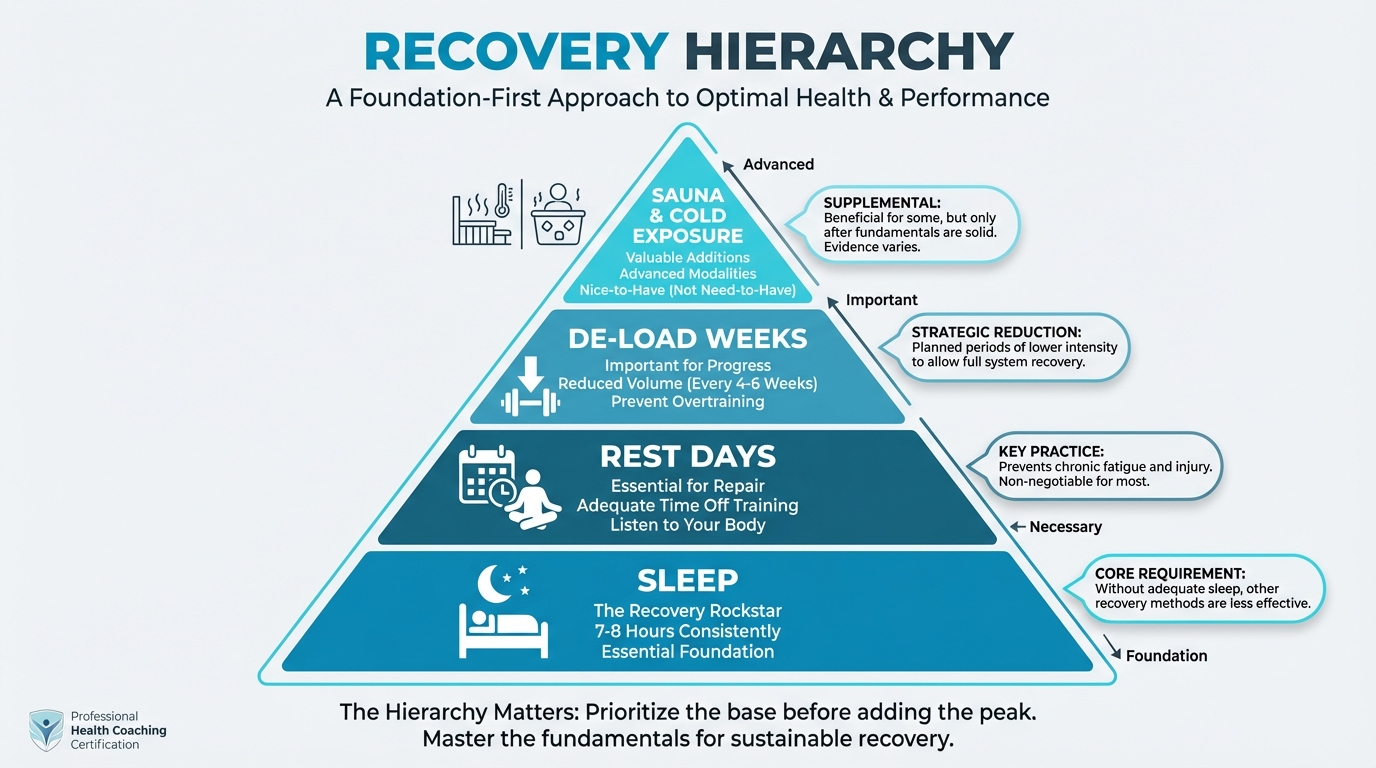

The hierarchy matters: Sleep is the recovery rockstar (Chapter 2.11). Rest days are essential. De-load weeks are important. And then—for those with access, interest, and solid fundamentals—sauna and cold exposure can be valuable additions. They're nice-to-have, not need-to-have.

Figure: Sleep → Rest Days → De-load → Sauna/Cold

Your clients will ask about cold plunges and sauna protocols. They've heard the podcasts. Your job is to help them understand what the evidence actually shows, where the hype exceeds the data, and how these practices fit (or don't) into their life.

[CHONK 1: Recovery: When Adaptation Happens]¶

The Stress-Recovery-Adaptation Cycle¶

Training doesn't make you stronger; recovery does.

When you lift weights, you're creating microscopic damage in muscle tissue. When you do high-intensity intervals, you're depleting energy stores and generating oxidative stress. The workout itself is breakdown, a stimulus that signals your body: "We need to be better prepared for this next time."

Adaptation—getting stronger, faster, more resilient—happens during recovery. Your body repairs the damage, replenishes energy, and rebuilds systems slightly better than before. This is called supercompensation.[^1]

The formula is simple: Stress + Recovery = Adaptation. But here's where people go wrong: they assume more stress equals more adaptation. It doesn't. Without adequate recovery, you just accumulate damage. Eventually, you slide backward.

Why Recovery Gets Neglected¶

In a culture that celebrates "no days off" and "rise and grind," recovery feels like weakness. Many clients feel guilty for resting. They think more is always better.

As a coach, one of your most important roles is helping clients understand that recovery isn't optional. It's where the magic happens. Every elite athlete takes recovery seriously. Every world-class training program builds in recovery protocols. The people who don't recover well are the ones who plateau, get injured, or burn out.

The Recovery Hierarchy¶

Not all recovery interventions are created equal. Here's the hierarchy, based on evidence strength and accessibility:

Essential (everyone should prioritize):

- Sleep: 7-8 hours, consistent timing (see Chapter 2.11)

- Rest days: Built into training programs

- Basic stress management: Walking, breathing exercises, nature exposure (Chapter 2.12)

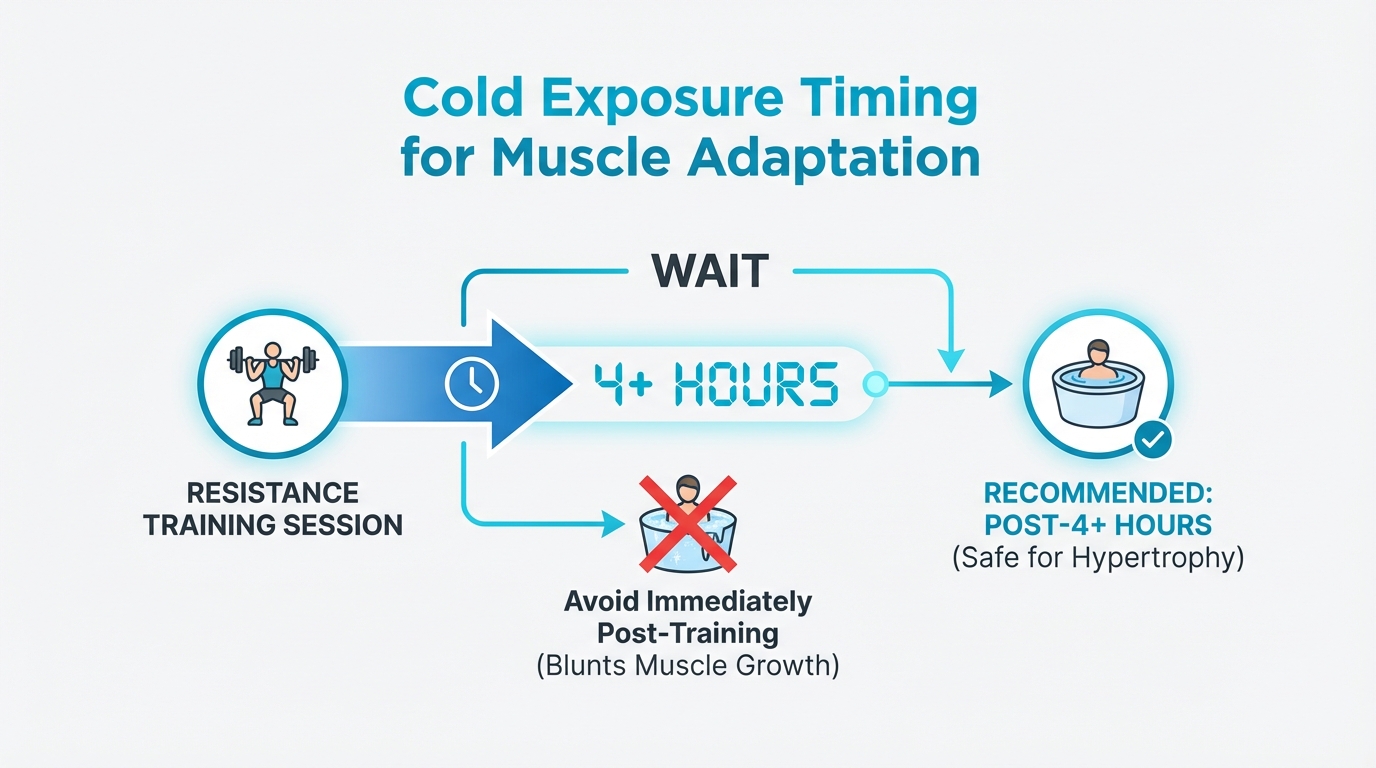

Figure: 4+ hours post-training recommendation

Valuable (worth doing if you can):

- De-load weeks: Reduced training volume every 4-6 weeks

- Self-myofascial release: Foam rolling, 5-10 minutes daily

- Active recovery: Light movement on rest days

Advanced (for those with fundamentals dialed in):

- Heat exposure: Sauna protocols

- Cold exposure: Ice baths, cold showers

- Contrast therapy: Alternating hot and cold

Be explicit with clients: If you're sleeping 5 hours a night, a cold plunge won't save you. The advanced interventions are finishing touches on a solid foundation. They're not substitutes for the basics.

Overtraining Syndrome: When Recovery Fails¶

When the balance tips too far toward stress and away from recovery, the result is overtraining syndrome (OTS). It's essentially your body saying: "I can't keep up with this anymore."

Warning signs of overtraining include:[^2]

- Persistent fatigue that doesn't improve with rest

- Declining performance despite continued training

- Mood changes: irritability, depression, anxiety

- Increased illness (frequent colds, infections)

- Sleep disturbances

- Loss of appetite or unexplained weight changes

- Elevated resting heart rate

OTS is a diagnosis of exclusion. There's no single blood test or marker that confirms it.[^3] What the research shows is that OTS often reflects more than just high training load. In one study, 44 of 67 measured parameters differed between OTS athletes and healthy athletes. Critically, chronic energy deficit, insufficient sleep, and high psychological stress were major predictors, not just training volume.[^4]

When to refer: If a client shows persistent OTS symptoms despite adequate recovery, refer them to their physician. OTS requires professional evaluation to rule out other medical conditions.

The Hormetic Stress Concept¶

Here's a concept that helps explain why some stressors can be beneficial: hormesis.

Hormesis is the idea that small, controlled doses of stress trigger adaptive responses that make you stronger. Think of it like a vaccine. A small dose of a pathogen trains your immune system to handle the real thing.

Exercise, heat exposure, and cold exposure are all forms of hormetic stress. In controlled doses, they trigger protective responses: your cells produce repair proteins, your mitochondria become more efficient, your stress-response systems upregulate.

The key word is "controlled": a brief sauna session at 176°F or a 2-minute cold shower is hormetic, whereas getting stuck in a hot car for hours is dangerous and falling through ice into a frozen lake is life-threatening.

What this means for your client: Recovery modalities like sauna and cold exposure aren't magic. They're controlled stressors that, when dosed appropriately, may trigger beneficial adaptations. The dose matters enormously.

[CHONK 2: Heat Exposure—Sauna and Longevity]¶

The Finnish Sauna Research: What We Know¶

The most compelling evidence for heat exposure comes from Finland, where sauna bathing is culturally embedded. Over 99% of Finns use saunas regularly. This has enabled large-scale observational studies that would be impossible elsewhere.

The headline findings are striking. In a cohort of over 2,300 middle-aged men followed for 21 years, compared to those who used sauna once per week:[^5]

- 4-7 sessions per week: 63% lower risk of sudden cardiac death (HR 0.37)

- 2-3 sessions per week: 25% lower risk of sudden cardiac death

Session duration also mattered. Men who stayed in the sauna longer than 19 minutes had 48% lower sudden cardiac death risk compared to those who stayed less than 11 minutes.[^6]

Similar patterns emerged for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease. In a 15-year follow-up of 1,688 adults, those using sauna 4-7 times weekly had approximately 77% lower fatal CVD risk compared to once-weekly users.[^7]

For dementia, the associations are also compelling. In a mixed-sex cohort of nearly 14,000 Finnish adults followed for 39 years, those taking 9-12 sauna baths per month had significantly lower dementia incidence compared to fewer than 4 per month (HR 0.47 over the first 20 years).[^8]

The Evidence Reality Check¶

Before you rush to prescribe 4x/week sauna protocols, let's be honest about what this evidence shows, and what it doesn't.

These are observational studies, not randomized controlled trials. People who use saunas frequently in Finland may differ from those who don't in dozens of ways: they may exercise more, socialize more, be healthier to begin with, have better healthcare access, or simply have lifestyles conducive to regular sauna use.

The most recent randomized trial data is more sobering. A 2025 meta-analysis of 20 RCTs testing passive heating interventions found no significant overall improvements in most cardiometabolic and vascular markers. Overall blood pressure change was about -2.5 mmHg, not statistically significant.[^9]

How do we reconcile this? A few possibilities:

- Observational studies capture long-term effects that short RCTs miss. The Finnish studies followed people for decades; most RCTs last weeks to months.

- Confounding factors inflate observational associations. Regular sauna users may simply be healthier people who do many health-promoting things.

- The truth is somewhere in between. Sauna may provide real benefits, but perhaps smaller than the dramatic observational associations suggest.

What this means for coaching: Present sauna as a promising practice with compelling observational data, but be honest that we don't have definitive proof of causation. For clients who enjoy heat exposure and have access, it's a reasonable addition to a recovery routine. For those who don't, they're not missing a life-or-death intervention.

| For DIY Learners |

|---|

| Applying this to yourself: Before investing in expensive recovery tools like cold plunges or infrared saunas, ask yourself: Are my fundamentals solid? Am I getting 7+ hours of sleep? Eating adequate protein? Exercising regularly? Managing stress? These "boring" basics deliver 90%+ of longevity outcomes. Recovery modalities are the "sand" after the "Big Rocks" are in place—nice additions, not foundations. |

Heat Exposure Protocols¶

If your client wants to incorporate sauna, here's what the protocols look like:

Traditional Finnish Sauna:

- Temperature: 176-195°F (80-90°C)

- Duration: 17-20 minutes per session

- Frequency: 4+ sessions per week (for maximum observed benefit)

- Type: Dry heat with low humidity

What About Infrared Saunas?

Infrared saunas operate at lower temperatures (120-140°F) and use infrared light to heat the body directly rather than heating the air. They're more accessible, easier to fit in homes, less intense, but the evidence base is weaker.

Most of the compelling mortality and dementia data comes from traditional Finnish saunas. Infrared sauna research is more limited and focused on specific applications (like athlete recovery and heart failure). One recent study found infrared sauna improved performance and reduced soreness in team sport athletes, but long-term outcomes haven't been studied.[^10]

If infrared is what your client has access to, it's likely better than no heat exposure. But the specific protocols from Finnish research may not translate directly.

Hot Baths: An Accessible Alternative

One interesting finding: a recent lab study comparing modalities found that hot-water immersion actually increased core temperature and acute anti-inflammatory responses more than dry saunas.[^11] For clients without sauna access, regular hot baths may provide some similar benefits, though this needs more research.

How Heat Exposure May Work: The Cellular Repair Crews¶

When you expose your body to heat stress, your cells respond by producing proteins called heat shock proteins (HSPs), particularly HSP70.

Think of heat shock proteins as your cells' repair crews. When heat (or other stress) damages proteins, HSPs help refold them back into their proper shape or tag them for disposal if they can't be fixed. They also protect proteins from getting damaged in the first place.[^12]

This is a hormetic response: controlled heat stress triggers production of protective machinery that may help your cells handle all kinds of stress, not just heat.

HSP70 capacity appears to decline with age. Studies in rats show that stress-induced HSP70 production falls by roughly 50% in aged cells compared to young cells.[^13] This may be one reason why maintaining the ability to mount a heat-shock response matters for healthy aging.

The cardiovascular benefits may work through similar mechanisms: improved endothelial function (how well blood vessels dilate), reduced arterial stiffness, better autonomic nervous system balance, and reduced chronic inflammation.[^14]

Safety First: Contraindications and Cautions¶

Heat exposure carries real risks for certain populations:

Contraindications (when to avoid or get physician clearance):

- Pregnancy

- Unstable cardiovascular disease

- Recent heart attack

- Severe aortic stenosis

- Unstable angina

Important Safety Practices:

- Stay hydrated: Drink water before, during, and after

- Don't combine with alcohol: This is dangerous and significantly increases cardiovascular risk

- Start gradually: Shorter durations, lower temperatures initially

- Know when to exit: Dizziness, nausea, excessive discomfort = leave immediately

- Don't push through: This is not about toughness

Coaching in Practice: "I Don't Have Access to a Sauna"¶

Client: "I've been hearing about sauna benefits on podcasts. Everyone says it's essential for longevity. But I don't have access to one—am I missing out?"

Coach: "Let's put this in perspective. The Finnish sauna research is interesting, but the people in those studies are doing sauna as part of a broader healthy lifestyle. They're not relying on sauna to compensate for poor sleep or no exercise."

Client: "So it's not as important as they make it sound?"

Coach: "It's not a life-or-death intervention. Sleep, movement, stress management—those are the big levers. Sauna is more like a nice finishing touch. If you don't have access, you're not missing something essential."

Client: "What about hot baths? Would that work?"

Coach: "There's some research suggesting hot baths might offer similar benefits—one study found hot water immersion actually increased core temperature more than dry saunas. So if hot baths feel relaxing to you, that's a reasonable option. The evidence is still developing."

Client: "I guess I've been stressing about not having a sauna."

Coach: "That's exactly what I want you to avoid. If you ever do get access to a sauna and enjoy it, great—add it to your routine. But don't let the absence of one thing derail everything else you're doing right."

[CHONK 3: Cold Exposure—Building Resilience]¶

The Current State of Cold Exposure Evidence¶

Cold exposure has exploded in popularity. Cold plunges, ice baths, and cold showers are promoted by podcasts and influencers as essential health practices. Your clients will ask about this. Here's what the evidence actually shows.

The honest summary: Cold exposure has plausible mechanisms and some promising findings, but the evidence base is preliminary. Most studies are small and short-term. The effects may be real but are likely more modest than the hype suggests.

What Cold Exposure Does (According to Research)¶

Increased Energy Expenditure:

When you're cold, your body burns more calories to stay warm. A meta-analysis found acute cold exposure increased resting energy expenditure by approximately 188 kcal/day compared to thermoneutral conditions.[^15] This happens through both shivering thermogenesis (you shake to generate heat) and non-shivering thermogenesis (your brown fat burns calories directly for heat).

Brown Fat Activation:

Brown adipose tissue (BAT), "brown fat," is a specialized type of fat that burns energy to generate heat. Cold exposure activates brown fat. Studies show increased BAT activity and volume with cold exposure.[^16]

Is this meaningful for health? Potentially. Brown fat activity may help with blood sugar regulation and metabolic health. But the magnitude of real-world impact remains unclear.

Recovery After Exercise:

Cold-water immersion (CWI) after strenuous exercise appears to reduce soreness and some muscle damage markers. A meta-analysis found:[^17]

- Reduced muscle soreness: SMD -0.89 (moderate effect)

- Reduced creatine kinase (muscle damage marker): SMD -0.85

- Improved muscle power at 24 hours: SMD 0.22 (small effect)

This supports using cold immersion for acute recovery between competitions or intense training sessions.

Stress Reduction and Mood:

Some studies find cold exposure reduces perceived stress and negative mood. One trial found that 15 minutes at 10°C reduced negative mood and cortisol at 3 hours post-immersion.[^18] A meta-analysis found perceived stress significantly reduced at 12 hours post-cold-water immersion.[^19]

Reduced Sick Days?

One intriguing finding: a narrative review noted that routine cold shower users reported approximately 29% fewer sick days from work.[^20] This is a single finding requiring replication, but it hints at possible immune benefits.

The Hypertrophy Trade-Off: Why Timing Matters¶

This is critical: If your client is trying to build muscle, cold exposure immediately after resistance training may sabotage their gains.

Multiple studies and meta-analyses show that routine post-exercise cold-water immersion attenuates muscle hypertrophy and strength adaptations. One systematic review found cold-water immersion immediately after resistance training reduced muscle growth compared to training alone (comparative effect approximately -0.22 SMD).[^21]

The proposed mechanism: cold blunts the inflammatory and anabolic signaling that drives muscle adaptation. The same processes that make muscles sore are also what makes them grow.

The practical rule: If muscle building is the goal, wait at least 4 hours after resistance training before cold exposure, or save cold exposure for non-lifting days. Cold can be useful for recovery between competitive events or after endurance sessions where hypertrophy isn't the primary goal.

Cold Shock Proteins: The Cold Version of Heat Shock¶

Just as heat triggers heat shock proteins, cold triggers cold shock proteins, particularly one called RBM3.

RBM3 is induced by cooling and appears to be neuroprotective. In mouse models of neurodegeneration, increasing RBM3 (through cooling or genetic manipulation) prevented synapse and neuron loss.[^22] The protein RTN3, which is regulated by RBM3, is a key downstream effector of this protection.[^23]

Does this translate to humans? We don't know yet. The neuroprotective effects are compelling in animal models, but human studies on cold exposure and brain health are limited.

The simple analogy: Cold exposure triggers protective proteins, similar to how heat triggers its own protective response. Think of it as your cells building cold-weather gear: controlled cold stress may help your cells handle stress of all kinds better.

Cold Exposure Protocols¶

If your client wants to incorporate cold exposure, here are evidence-based protocols:

Cold-Water Immersion (Ice Bath):

- Temperature: 50-55°F (10-13°C)

- Duration: 2-3 minutes per session

- Frequency: 2-4 times per week

Cold Showers:

- An accessible alternative

- End a regular shower with 30-90 seconds of cold water

- Build tolerance gradually

Building Tolerance:

- Start with cold exposure at the end of a warm shower

- Begin with shorter durations (30 seconds) and work up

- Focus on controlled breathing rather than gasping or tensing

Gender Considerations¶

Women may respond differently to cold exposure, particularly across the menstrual cycle.

What the research shows:

- Core body temperature is approximately 0.3-0.7°C higher in the luteal phase (post-ovulation) compared to the follicular phase[^24]

- Some studies suggest luteal-phase women perceive coolness earlier and add clothing sooner during cooling protocols[^25]

- However, when matched for body size, women and men show similar cold-induced thermogenesis[^26]

- A recent female-specific RCT found neither cold nor hot water immersion improved recovery markers at 24-72 hours versus passive rest[^27]

Practical guidance: The menstrual cycle doesn't require major protocol changes, but coaches should be aware that:

- Women in the luteal phase may feel colder at the same temperatures

- Consider slightly warmer water (55-60°F instead of 50-55°F) or shorter durations during the luteal phase if cold discomfort is significant

- Individual perception matters. Some women notice no difference; others do

Safety First: Cold Exposure Risks¶

Cold exposure carries real risks:

Contraindications:

- Raynaud's disease (blood vessel disorder affecting fingers/toes)

- Cold urticaria (allergic reaction to cold)

- Unstable cardiovascular disease

- Uncontrolled hypertension

Important Safety Practices:

- Never do cold-water immersion alone in deep water. Drowning risk is real if you experience cold shock or incapacitation.

- Build tolerance gradually. Start with cold showers before attempting full immersion.

- Know the exit signals: Numbness, confusion, uncontrollable shivering, or inability to think clearly = get out immediately

- Warm up afterward: Have warm clothing and a warm environment ready

[CHONK 4: Addressing the "Optimization" Culture]¶

When Clients Come In Hot (or Cold) About Biohacking¶

Let's be direct: your clients will ask about protocols they've heard on podcasts or seen on social media. They'll mention specific influencers. They'll want to know if they should be doing 4-minute ice baths at 45°F or 20-minute saunas at 195°F.

This isn't a problem to dismiss; it's an opportunity to coach.

First, acknowledge their interest. Someone researching recovery modalities is engaged in their health. That's positive. Don't shut them down or make them feel foolish for being curious.

Second, help them understand the evidence landscape. Many popular protocols are extrapolated from small studies, animal research, or mechanistic speculation. The influencers promoting them often have financial incentives (selling cold plunge tubs, supplement stacks, or membership programs). This doesn't mean the protocols are wrong. It means the confidence level often exceeds the evidence.

Third, help them prioritize. The "optimization" mindset can create anxiety when someone feels they're not doing enough. A client obsessing over cold plunge timing while getting 5 hours of sleep has their priorities backward.

The "35-Year-Old Optimizer" vs. Everyone Else¶

Here's a useful distinction: There's a specific type of client for whom advanced recovery protocols make sense: someone who already has their fundamentals dialed in.

The "35-year-old optimizer" profile:

- Already sleeping 7-8 hours consistently

- Already exercising 4-5 times per week with good programming

- Already eating well with adequate protein

- Has disposable income and time

- Enjoys quantifying and optimizing

- No major stressors destabilizing their baseline

For this client, adding sauna sessions or structured cold exposure might provide marginal gains and personal satisfaction. They're optimizing at the margins, fine-tuning an already well-running machine.

Most clients don't fit this profile. They're juggling work, family, stress, and trying to find 30 minutes to exercise. For them, the fundamentals—sleep, basic movement, stress management—will deliver far more benefit than any advanced protocol.

The Practical Reality Test¶

Before recommending any recovery intervention, run it through this filter:

Can this client actually do this?

- Does a busy healthcare worker with two kids have time for 4x/week sauna sessions?

- Does someone renting a small apartment have access to a cold plunge?

- Will this add stress (scheduling, cost, complexity) or reduce it?

Is this addressing a real limitation?

- What's actually holding this client back from their goals?

- Would improving sleep give them more benefit than adding cold exposure?

- Are they solving the right problem?

Is this sustainable?

- Will they still be doing this in 6 months?

- Does it fit their life or fight against it?

When to Embrace the Interest¶

Some clients will genuinely enjoy sauna rituals or cold plunges. For them, these practices aren't just about physiological benefits. They're about self-care, ritual, mental resilience, and taking time for recovery.

That's valuable! The psychological benefits of feeling like you're taking care of yourself shouldn't be dismissed. If a client finds cold showers invigorating and it helps them feel disciplined and resilient, that's a win, even if the physiological benefits are modest.

The key is helping clients hold both truths: "This practice is beneficial for me" AND "The evidence for dramatic health effects is preliminary." Both can be true simultaneously.

Coaching in Practice: The Over-Enthusiastic Optimizer¶

Client: "I just bought a cold plunge tub and I'm starting the 4-minute daily protocol I saw online. I'm also going to add sauna 5 times a week. And I read about this supplement stack that enhances the effects..."

Coach: "I love that you're invested in your recovery—that's going to serve you well. Let me share some things that might help you get the most out of this."

Client: "Okay, what should I know?"

Coach: "First, the evidence for specific protocols like '4 minutes at exactly 50°F' is actually pretty limited. The research uses various temperatures and durations, and we don't have clear optimal doses. Starting with 2-3 minutes and seeing how you feel is probably wise."

Client: "But the guy online seemed so confident about the exact numbers."

Coach: "That's the thing about podcasts—the confidence often exceeds the evidence. Second question: How's your sleep been lately? How's stress?"

Client: "Sleep's been rough. Maybe 5-6 hours. Work has been crazy."

Coach: "That's what I suspected. Recovery modalities work best when the fundamentals are solid. If sleep is struggling, that's where I'd focus first. The cold plunge and sauna become nice additions once the basics are dialed in—but they can't compensate for poor sleep."

Client: "So I should hold off on all this?"

Coach: "Not necessarily. But maybe start with 2-3 cold sessions and 2-3 sauna sessions per week, not daily everything. Your body needs time to adapt. Watch for diminishing returns—more isn't always better. And most importantly, I don't want recovery to become another source of stress. If tracking all these protocols feels like a second job, we've missed the point."

[CHONK 5: Contrast Therapy and Other Recovery Modalities]¶

Contrast Therapy: The Hot-Cold Combo¶

Contrast therapy alternates between heat and cold exposure. The theory is that cycling between vasodilation (heat) and vasoconstriction (cold) creates a "pumping" action that may enhance blood flow and waste clearance.

Standard Protocol:

- Hot: 10-20 minutes (sauna or hot tub)

- Cold: 2-5 minutes (cold plunge or cold shower)

- Repeat: 2-4 rounds

- Frequency: 2-4 times per week

Evidence assessment: Limited. Few rigorous studies exist in healthy adults. Athletes report subjective benefits for recovery, but controlled data is sparse. Contrast therapy may aid blood flow and perceived recovery, but it hasn't been shown superior to simpler modalities for measurable outcomes.[^28]

Practical consideration: Contrast therapy requires access to both hot and cold facilities, which limits accessibility. If a client has access and enjoys it, there's no reason to discourage it. But it's not essential.

Self-Myofascial Release: Foam Rolling¶

Foam rolling is one of the most accessible recovery modalities. You can do it at home with a $30 foam roller.

What the research shows:

- Improved range of motion: Multi-week foam rolling programs increase joint range of motion by approximately 5-10% without impairing strength or jump performance[^29]

- Reduced soreness: Foam rolling reduces delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS) at 48-72 hours post-exercise[^30]

- Reduced muscle stiffness: During DOMS recovery, foam rolling significantly reduced elevated muscle tone and stiffness compared to rest[^31]

- Lactate clearance: Foam rolling reduced blood lactate 30 minutes post-exercise compared to passive rest[^32]

What it doesn't do: Foam rolling is not superior to other warm-up methods for acute flexibility. A meta-analysis found foam rolling and static stretching weren't better than other warm-ups for immediate flexibility gains.[^33] Its benefits are more about recovery and chronic flexibility than acute preparation.

Practical protocol:

- Duration: 5-10 minutes daily

- Technique: Roll slowly over target muscles, pausing on tender spots

- Pressure: Moderate, uncomfortable but not painful

- Timing: Can be used pre-workout (for warm-up) or post-workout (for recovery)

Foam rolling is comparable to manual massage for range of motion and perceived recovery, at a fraction of the cost.[^34] It's a practical, evidence-supported tool for any client.

Massage and Bodywork¶

Professional massage provides real but modest benefits for recovery. Research supports effects on range of motion, perceived recovery, and some soreness reduction.[^35]

Practical consideration: The limiting factor is cost and accessibility. For clients who can afford regular massage (2x/month as suggested in the protocol), it's a reasonable addition. For most clients, self-myofascial release provides similar benefits at much lower cost.

De-load Weeks: Programmed Recovery¶

De-loading is a planned period of reduced training stress, typically reducing volume by 40-50% every 4-6 weeks.

Why de-load? Training creates fatigue that accumulates over weeks. A de-load allows that accumulated fatigue to dissipate, setting up the next training block for better performance and adaptation.

What the research shows:

- Athletes commonly de-load for approximately 6 days every 5-6 weeks[^36]

- Implementation typically involves reducing volume and effort (more reps in reserve) while maintaining exercise selection and frequency

- One RCT found that a one-week de-load implemented as complete training cessation did not improve adaptations and actually resulted in smaller lower-body strength gains compared to continuous training[^37]

Key insight: The research suggests de-loading by reducing volume/effort is better than stopping entirely. Complete rest may lead to detraining without providing additional recovery benefit.

Practical protocol:

- Every 4-6 weeks, reduce training volume by 40-50%

- Maintain training frequency and exercise selection

- Can reduce weight by 10-20% or reduce sets by 40-50%

- Return to normal training after one week

Active Recovery: Light Movement¶

Light movement on rest days—walking, swimming, easy cycling—may support recovery better than complete rest. The movement promotes blood flow without adding significant stress.

This is simple and free. For most clients, encouraging a daily walk is more impactful than recommending complex recovery protocols.

[CHONK 6: Integrating Recovery Into Life]¶

The Weekly Recovery Picture¶

Here's how recovery modalities might fit into a typical week:

Daily:

- 7-8 hours of sleep (non-negotiable)

- 5-10 minutes of foam rolling (if desired)

- Light movement/walking (especially on rest days)

Weekly:

- 1-2 rest days from structured training

- 2-4 sauna sessions (if available and enjoyed)

- 2-3 cold exposure sessions (if desired, not immediately post-strength training)

Monthly:

- De-load week every 4-6 weeks

- Massage (if accessible and affordable)

Matching Recovery to Training Phase¶

Recovery needs change based on training intensity:

High-intensity training blocks: More attention to recovery, potentially more frequent de-loads, prioritize sleep above all else

Competition or testing phases: Recovery modalities can help between events; cold water immersion may be useful for acute recovery between competitions (where hypertrophy isn't the goal)

Base-building phases: Standard recovery practices, less need for aggressive intervention

When to Refer¶

Refer clients to their physician if:

- Persistent fatigue doesn't improve with adequate recovery interventions

- Signs of overtraining syndrome persist despite addressing sleep, nutrition, and stress

- Any cardiovascular symptoms during temperature exposure (chest pain, significant palpitations, shortness of breath)

- History of cardiovascular disease and they want to start heat exposure protocols

- Pregnancy and questions about temperature exposure safety

- History of Raynaud's, cold urticaria, or cold injury before starting cold exposure

[CHONK 7: Deep Health Integration]¶

Recovery practices affect multiple dimensions of Deep Health:

Physical¶

This is the primary dimension. Recovery allows:

- Tissue repair after training

- Inflammation resolution

- Adaptation and supercompensation

- Energy restoration

Without adequate recovery, physical health deteriorates despite training efforts.

Mental¶

Recovery practices like cold exposure and sauna may support mental clarity and stress resilience. This hasn't been proven causally, but it's a plausible mechanism and aligns with client reports. Some people find that controlled exposure to discomfort—cold showers, sauna heat—builds mental toughness and a sense of agency over their body's responses.

Emotional¶

Recovery practices can serve as self-care rituals. Taking time to do something for your body—foam rolling, a warm bath, a sauna session—communicates to yourself that you're worth taking care of.

However, watch for the opposite: recovery becoming another source of anxiety or obligation. The goal is for recovery practices to reduce stress, not add to it. If a client is stressed about optimizing their cold plunge protocol, something has gone wrong.

Social¶

Recovery practices can be social. Saunas in Nordic cultures are often communal. Walking with a friend is active recovery. Even foam rolling can happen during conversation.

For clients who struggle with social connection, recovery practices that involve others can provide dual benefits.

Avoiding the Recovery Trap¶

Some clients can become obsessive about recovery metrics: constantly checking HRV, stress about sleep scores, anxious about hitting recovery targets. This is the opposite of recovery.

Signs of recovery obsession:

- Checking recovery metrics multiple times daily

- Feeling anxious when recovery scores are "bad"

- Skipping social events or life activities to optimize recovery

- Recovery tracking becoming a source of stress rather than information

The antidote: Use recovery data for trends, not for moment-to-moment decisions. A few nights of poor sleep won't derail health. The goal is "good enough" recovery that's sustainable, not perfect optimization that becomes its own stressor.

Key Takeaways¶

-

Recovery is when adaptation happens. Without adequate recovery, training becomes breakdown rather than buildup.

-

The hierarchy matters: Sleep and rest are essential. De-loads are important. Sauna and cold are advanced, nice-to-have, not need-to-have.

-

Finnish sauna research is compelling but observational. The associations with reduced cardiovascular mortality and dementia are striking, but causation isn't proven. RCT data is less impressive.

-

Cold exposure evidence is preliminary. Benefits are plausible but likely modest. Most importantly: wait 4+ hours after resistance training before cold exposure to avoid blunting muscle growth.

-

Gender considerations exist but don't require major protocol changes. Women in the luteal phase may feel colder; consider slightly warmer water or shorter durations if discomfort is significant.

-

De-load by reducing volume, not by stopping entirely. Complete training cessation during de-load weeks may disadvantage strength development.

-

Foam rolling is accessible and evidence-supported. Five to ten minutes daily can improve range of motion and reduce soreness.

-

The biohacking conversation requires nuance. Acknowledge client interest, present evidence honestly, help them prioritize fundamentals first.

Study Guide Questions¶

These questions help you review the material and prepare for the chapter exam.

-

What is the stress-recovery-adaptation cycle, and why does recovery matter for adaptation?

-

According to Finnish observational studies, what sauna frequency was associated with the lowest cardiovascular mortality risk? What are the limitations of this evidence?

-

Why should clients wait at least 4 hours after resistance training before doing cold-water immersion?

-

What is hormesis, and how does it apply to heat and cold exposure?

-

What are three warning signs of overtraining syndrome?

-

How should coaches respond when clients ask about popular cold plunge protocols they've heard about on podcasts?

Self-reflection questions:

-

How much intentional recovery do you build into your week? Are you recovering well enough to adapt, or pushing through fatigue?

-

Before investing in expensive recovery tools (cold plunge, sauna, etc.), are your fundamentals solid? Sleep? Nutrition? Stress management? What's actually limiting your recovery right now?

Deep Dives¶

Want to go deeper? These supplemental articles explore key topics from this chapter in more detail.

- Heat Shock Proteins. Molecular mechanisms (for interested learners)

- Cold Adaptation Science. Brown fat, cold shock proteins

References¶

-

Fundamentals of resistance training: progression and exercise prescription. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000121945.36635.61

-

Meeusen R, Duclos M, Foster C, Fry A, Gleeson M, Nieman D, et al. Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of the overtraining syndrome: Joint consensus statement of the European College of Sport Science (ECSS) and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). European Journal of Sport Science. 2012;13(1):1-24. doi:10.1080/17461391.2012.730061

-

Carrard J, Rigort A, Appenzeller-Herzog C, Colledge F, Königstein K, Hinrichs T, et al. Diagnosing Overtraining Syndrome: A Scoping Review. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 2021;14(5):665-673. doi:10.1177/19417381211044739

-

Cadegiani FA, Kater CE. Novel insights of overtraining syndrome discovered from the EROS study. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine. 2019;5(1):e000542. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000542

-

Laukkanen T, Khan H, Zaccardi F, Laukkanen JA. Association Between Sauna Bathing and Fatal Cardiovascular and All-Cause Mortality Events. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2015;175(4):542. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8187

-

Laukkanen T, Kunutsor SK, Khan H, Willeit P, Zaccardi F, Laukkanen JA. Sauna bathing is associated with reduced cardiovascular mortality and improves risk prediction in men and women: a prospective cohort study. BMC Medicine. 2018;16(1). doi:10.1186/s12916-018-1198-0

-

.

-

Knekt P, Järvinen R, Rissanen H, Heliövaara M, Aromaa A. Does sauna bathing protect against dementia?. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2020;20:101221. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101221

-

Hamaya R, Joyama Y, Miyata T, Fuse S, Yamane N, Maruyama N, et al. Non-acute effects of passive heating interventions on cardiometabolic risk and vascular health: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. American Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2025;23:101082. doi:10.1016/j.ajpc.2025.101082

-

University of Jyväskylä. Infrared Sauna Shows Promising Benefits for Team-Sport Athletes. 2025. https://www.jyu.fi/en/news/infrared-sauna-shows-promising-benefits-for-team-sport-athletes

-

University of Oregon (Bowerman Sports Science Center). Hot tubs may offer greater health benefits than saunas. News-Medical; 2025. https://www.news-medical.net/news/20250626/Hot-tubs-may-offer-greater-health-benefits-than-saunas.aspx

-

Venediktov AA, Bushueva OY, Kudryavtseva VA, Kuzmin EA, Moiseeva AV, Baldycheva A, et al. Closest horizons of Hsp70 engagement to manage neurodegeneration. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience. 2023;16. doi:10.3389/fnmol.2023.1230436

-

.

-

Brunt VE, Minson CT. Heat therapy: mechanistic underpinnings and applications to cardiovascular health. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2021;130(6):1684-1704. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00141.2020

-

Huo C, Song Z, Yin J, Zhu Y, Miao X, Qian H, et al. Effect of Acute Cold Exposure on Energy Metabolism and Activity of Brown Adipose Tissue in Humans: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Physiology. 2022;13. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.917084

-

.

-

Moore E, Fuller JT, Buckley JD, Saunders S, Halson SL, Broatch JR, et al. Impact of Cold-Water Immersion Compared with Passive Recovery Following a Single Bout of Strenuous Exercise on Athletic Performance in Physically Active Participants: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis and Meta-regression. Sports Medicine. 2022;52(7):1667-1688. doi:10.1007/s40279-022-01644-9

-

Reed EL, Whittman EK, Park TE, Chapman CL, Larson EA, Kaiser BW, et al. Cardiovascular And Mood Responses To An Acute Bout Of Cold Water Immersion. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2022;54(9S):345-345. doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000879348.09119.c9

-

Cain T, Brinsley J, Bennett H, Nelson M, Maher C, Singh B. Effects of cold-water immersion on health and wellbeing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 2025;20(1):e0317615. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0317615

-

.

-

Piñero A, Burke R, Augustin F, Mohan AE, DeJesus K, Sapuppo M, et al. Throwing cold water on muscle growth: A systematic review with meta‐analysis of the effects of postexercise cold water immersion on resistance training‐induced hypertrophy. European Journal of Sport Science. 2024;24(2):177-189. doi:10.1002/ejsc.12074

-

Peretti D, Smith HL, Verity N, Humoud I, de Weerd L, Swinden DP, et al. TrkB signaling regulates the cold-shock protein RBM3-mediated neuroprotection. Life Science Alliance. 2021;4(4):e202000884. doi:10.26508/lsa.202000884

-

Bastide A, Peretti D, Knight JR, Grosso S, Spriggs RV, Pichon X, et al. RTN3 Is a Novel Cold-Induced Protein and Mediates Neuroprotective Effects of RBM3. Current Biology. 2017;27(5):638-650. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.047

-

Baker FC, Siboza F, Fuller A. Temperature regulation in women: Effects of the menstrual cycle. Temperature. 2020;7(3):226-262. doi:10.1080/23328940.2020.1735927

-

.

-

Mengel LA, Seidl H, Brandl B, Skurk T, Holzapfel C, Stecher L, et al. Gender Differences in the Response to Short-term Cold Exposure in Young Adults. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2020;105(5):e1938-e1948. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa110

-

Wellauer V, Clijsen R, Bianchi G, Riggi E, Hohenauer E. No acceleration of recovery from exercise-induced muscle damage after cold or hot water immersion in women: A randomised controlled trial. PLOS ONE. 2025;20(5):e0322416. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0322416

-

Kunutsor SK, Lehoczki A, Laukkanen JA. The untapped potential of cold water therapy as part of a lifestyle intervention for promoting healthy aging. GeroScience. 2024;47(1):387-407. doi:10.1007/s11357-024-01295-w

-

Konrad A, Nakamura M, Tilp M, Donti O, Behm DG. Foam Rolling Training Effects on Range of Motion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Medicine. 2022;52(10):2523-2535. doi:10.1007/s40279-022-01699-8

-

Michalak B, Kopiczko A, Gajda R, Adamczyk JG. Recovery effect of self‐myofascial release treatment using different type of a foam rollers. Scientific Reports. 2024;14(1). doi:10.1038/s41598-024-66577-x

-

Szajkowski S, Pasek J, Cieślar G. Foam Rolling or Percussive Massage for Muscle Recovery: Insights into Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS). Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2025;10(3):249. doi:10.3390/jfmk10030249

-

Recovery effect of self-myofascial release treatment using different types of foam rollers. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66577-x

-

Fleckenstein H, et al.. Foam rolling and stretching do not provide superior acute flexibility and stiffness improvements compared to any other warm-up intervention: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Sport Health Sci; 2024. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38244921/

-

Kerautret Y, Di Rienzo F, Eyssautier C, Guillot A. Selective Effects of Manual Massage and Foam Rolling on Perceived Recovery and Performance: Current Knowledge and Future Directions Toward Robotic Massages. Frontiers in Physiology. 2020;11. doi:10.3389/fphys.2020.598898

-

.

-

Rogerson D, Nolan D, Korakakis PA, Immonen V, Wolf M, Bell L. Deloading Practices in Strength and Physique Sports: A Cross-sectional Survey. Sports Medicine - Open. 2024;10(1). doi:10.1186/s40798-024-00691-y

-

Coleman M, Burke R, Augustin F, Piñero A, Maldonado J, Fisher JP, et al. Gaining more from doing less? The effects of a one-week deload period during supervised resistance training on muscular adaptations. PeerJ. 2024;12:e16777. doi:10.7717/peerj.16777