Unit 2: Core Interventions—The Protocol¶

Chapter 2.12: Stress and Mental Health¶

[CHONK: 1-minute summary]

The big idea¶

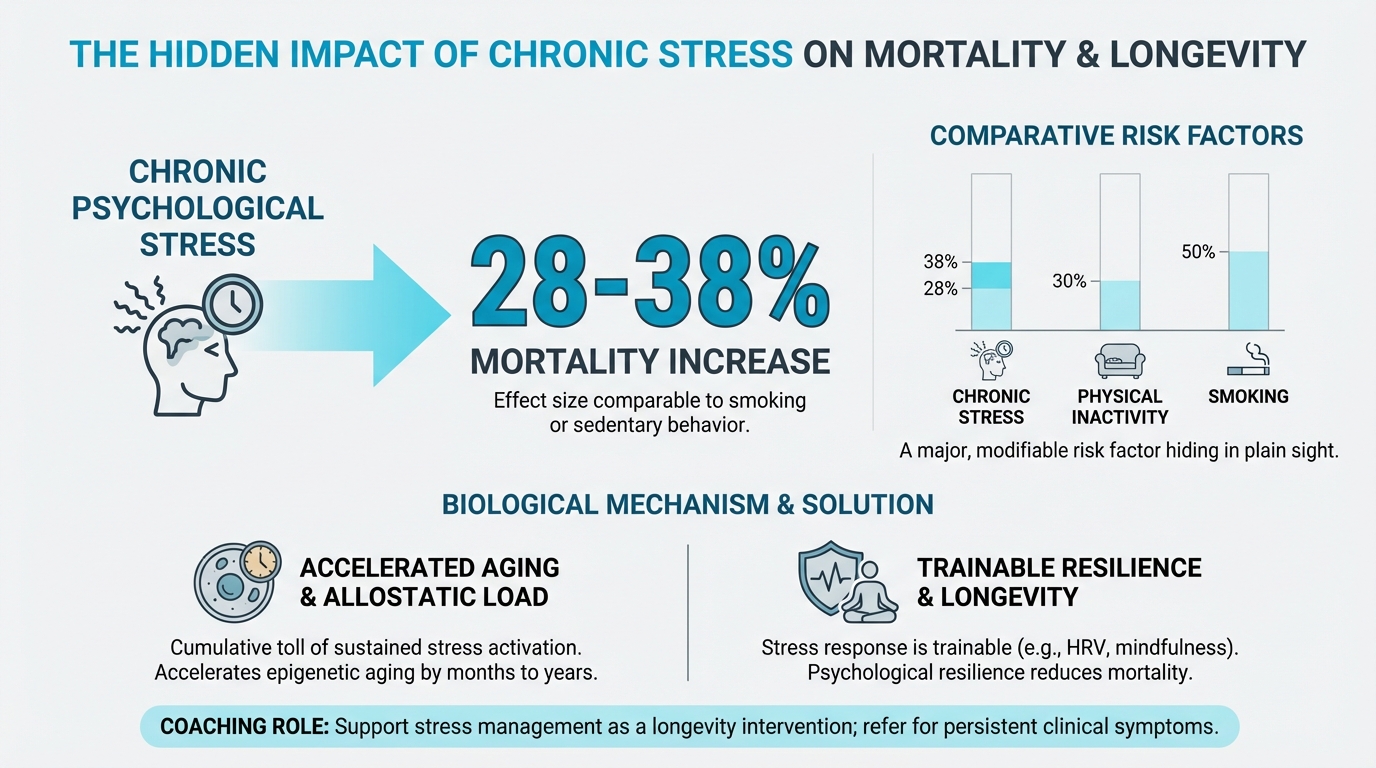

Stress is the hidden accelerator of aging. While most longevity conversations focus on diet, exercise, and sleep, chronic psychological stress independently increases mortality by 28-38 percent, an effect size comparable to smoking or sedentary behavior.[^1] This isn't about occasional deadlines or traffic jams. It's about the cumulative biological toll of sustained stress activation, what researchers call "allostatic load."

Here's what's hopeful: stress management is trainable. Unlike your genetics, your stress response is modifiable through evidence-based practices that activate your parasympathetic nervous system, your body's recovery mode. Meditation, breathwork, nature exposure, and resilience-building practices don't just feel good; they measurably reduce biological aging markers and mortality risk.

This chapter bridges stress physiology with practical coaching application. You'll learn the biological mechanisms linking stress to accelerated aging, specific parasympathetic activation techniques backed by research, and how to build multi-dimensional resilience in clients. Critically, you'll also learn where your scope ends, when stress-related presentations require referral to licensed mental health professionals.

Key takeaways:

- Chronic stress increases mortality by 28-38% and accelerates epigenetic aging by months to years

- Heart rate variability (HRV) is a trainable biomarker of stress resilience

- Meditation (MBSR, TM) shows equivalent effects to medication for anxiety disorders

- Breathwork produces moderate stress reduction (effect size: -0.35)

- Nature exposure reduces cortisol and increases parasympathetic activity within 20 minutes

- Psychological resilience reduces mortality by 20-35% per standard deviation increase

- Coaches support stress management. They do NOT diagnose or treat mental health conditions

- Know when to refer: persistent symptoms ≥2 weeks, safety concerns, functional impairment

[CHONK: Section 1 - The Stress-Aging Connection]

The stress-aging connection: Your body's hidden wear and tear¶

The mortality stakes¶

Let's start with numbers that should get your attention. In a Chinese longitudinal study following 19,236 older adults, those with high social stress had 28-38 percent higher all-cause mortality compared to low-stress peers.[^1] This wasn't just feeling stressed. Researchers measured chronic stress burden and followed participants for years. The stress-mortality link held even after controlling for health behaviors, socioeconomic status, and existing diseases.

This effect size matters. For comparison, physical inactivity increases mortality by about 30 percent. Smoking increases it by about 50 percent. Chronic stress sits in that same neighborhood, a major, modifiable risk factor hiding in plain sight.

What stress does to your biology¶

When you encounter a stressor, your body launches a coordinated response designed to help you survive the threat. Your hypothalamus signals your pituitary gland, which signals your adrenal glands to release cortisol. This is the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in action. Simultaneously, your sympathetic nervous system triggers the release of adrenaline: heart rate increases and blood pressure rises, blood sugar becomes available for muscles, digestion slows, and immune responses shift.

This stress response is adaptive when it's acute and resolves. The problem is when it doesn't turn off, when chronic stress keeps the system partially activated day after day, week after week.

What chronic stress activation does:

- Cortisol stays elevated: Normally, cortisol follows a pattern, high in the morning, declining through the day. Chronic stress flattens this rhythm and keeps levels higher than they should be.

- The cortisol/DHEAS ratio shifts: DHEA-sulfate (DHEAS) is a protective hormone that opposes some of cortisol's effects. With chronic stress, cortisol rises while DHEAS declines, creating a more damaging ratio.[^2]

- Downstream hormonal cascades break: Chronic HPA activation suppresses the HPG axis (affecting sex hormones) and HPT axis (affecting thyroid function). This explains some of the reproductive and metabolic effects of chronic stress.[^3]

- Inflammation increases: Cortisol is actually anti-inflammatory in the short term, but chronic stress creates a state of low-grade systemic inflammation, a hallmark of aging itself.[^4]

Epigenetic age acceleration: Stress ages you faster¶

Here's where the research gets remarkable—and sobering. Your body has biological "clocks" that estimate your cellular age based on patterns of DNA methylation (chemical marks on your DNA that affect gene expression). These epigenetic clocks—with names like GrimAge, PhenoAge, and DunedinPACE—predict mortality and disease better than chronological age.

Chronic stress accelerates these clocks.

Studies show that high stress exposure can add months to years of biological aging. One meta-analysis found stress associated with +0.34 to +2.29 years of epigenetic age acceleration, depending on the clock and population studied.[^5] Think about that: chronic stress can make your cells years older than your birth certificate suggests.

The encouraging news: these clocks appear to be reversible. Research on major stressors (like surgery or pregnancy) shows that epigenetic age spikes during the acute stress period but recovers afterward.[^6] This suggests that reducing chronic stress load could slow or even reverse some biological aging, though long-term intervention studies are still limited.

Allostatic load: The cumulative toll¶

Allostatic load is the scientific term for the "wear and tear" your body accumulates from repeated stress responses. Think of it as the biological cost of constantly adapting to challenges.

Researchers measure allostatic load by combining biomarkers across systems: cortisol patterns, blood pressure, inflammatory markers (like C-reactive protein), metabolic markers (blood sugar, cholesterol), and cardiovascular indicators. High scores predict worse outcomes across the board.

What the numbers show:

- High allostatic load is associated with 22 percent higher all-cause mortality[^7]

- Cardiovascular mortality is even more affected: 31 percent higher with high allostatic load[^7]

- The relationship is dose-dependent: more wear and tear, higher risk

One surprising finding: lifestyle factors like diet and exercise mediate only about 7 percent of the stress-mortality connection.[^8] This tells us something important: stress isn't just causing problems because stressed people eat worse or exercise less. Stress has direct biological effects that require direct interventions.

Coaching in Practice: "Stress Is Just Part of Life"¶

Client: "Everyone is stressed. It's just how life is now. I don't see why we need to focus on it."

Coach: "You probably know that sleep, exercise, and nutrition matter for health. What the research shows is that chronic stress is in the same category—it independently increases mortality risk by about 30 percent and literally accelerates biological aging."

Client: "Wait, really? 30 percent?"

Coach: "That's the data. This isn't about feeling relaxed, though that's nice. It's about protecting your cells from unnecessary wear and tear. Chronic stress creates measurable biological damage."

Client: "So what do I do about it? I can't quit my job."

Coach: "You don't have to quit your job. Unlike your genes, your stress response is trainable. The practices we'll work on aren't just stress relief—they're longevity interventions. And they work even if your life stays busy."

Figure: 28-38% mortality increase from chronic stress

[CHONK: Section 2 - The Autonomic Nervous System and Recovery]

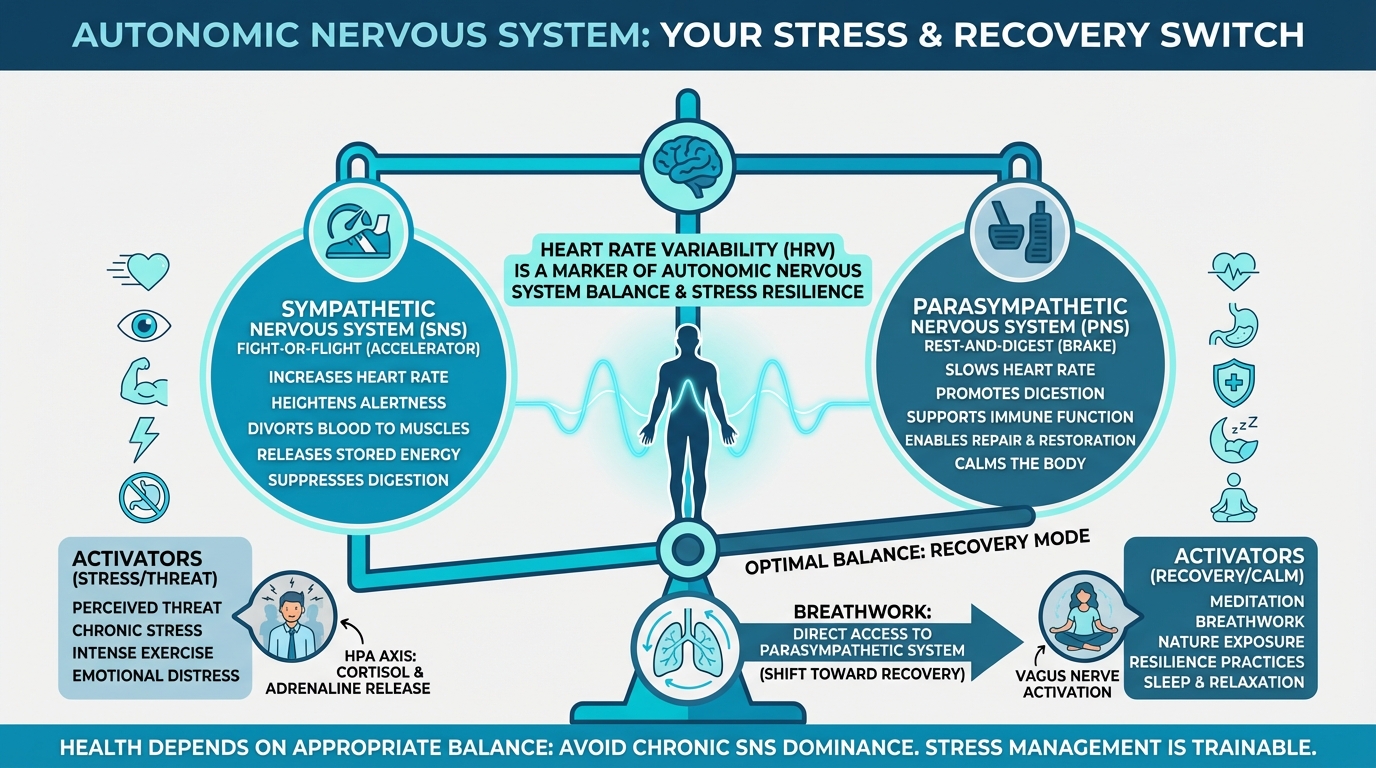

Figure: SNS vs PNS balance visual

The autonomic nervous system: Your stress and recovery switch¶

Two systems, one goal¶

Your autonomic nervous system—the part of your nervous system that operates largely without conscious control—has two major branches that work in opposition:

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS): Often called "fight-or-flight," this branch activates during stress or perceived threat. It increases heart rate, diverts blood to muscles, releases stored energy, heightens alertness, and suppresses non-essential functions like digestion. It's your body's accelerator pedal.

The parasympathetic nervous system (PNS): Often called "rest-and-digest," this branch activates during recovery and relaxation. It slows heart rate, promotes digestion, supports immune function, and enables repair and restoration. It's your body's brake pedal.

Health depends on appropriate balance between these systems. Problems arise when the SNS is chronically dominant, when the accelerator is pressed even when there's no real threat.

The vagus nerve: Your recovery superhighway¶

The vagus nerve is the primary carrier of parasympathetic signals. It's the longest cranial nerve in your body, running from your brainstem down through your neck and into your chest and abdomen. It connects your brain to your heart, lungs, gut, and many other organs.

"Vagal tone" refers to the activity level of this nerve. Higher vagal tone means your parasympathetic system is stronger, you can recover from stress more quickly, your heart rate variability is higher, and your inflammatory responses are better regulated.

What the vagus nerve does:

- Heart: Slows heart rate, increases heart rate variability

- Lungs: Influences breathing depth and rhythm

- Gut: Stimulates digestion and gut motility; part of the gut-brain axis

- Immune system: The "cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway" helps regulate inflammatory responses

- Communication: Carries sensory information from organs back to the brain (80% of vagus nerve fibers are afferent, carrying information up to the brain)

Here's why this matters for coaching: vagal tone is trainable. Practices like slow breathing, meditation, and cold exposure can increase vagal tone, strengthening your parasympathetic capacity.[^9]

Heart rate variability: Your resilience biomarker¶

Heart rate variability (HRV) is the variation in time between successive heartbeats. Despite what you might think, a healthy heart doesn't beat like a metronome. It constantly adjusts based on demands, and this variability reflects your autonomic nervous system's flexibility.

Higher HRV generally indicates:

- Greater parasympathetic tone

- Better ability to adapt to stressors

- More resilient stress response

- Higher overall cardiovascular health

Lower HRV generally indicates:

- Sympathetic dominance

- Reduced adaptive capacity

- Higher stress load

- Potential cardiovascular risk

HRV isn't just a stress marker. It predicts outcomes. Research shows that higher HRV is associated with lower mortality risk, while low HRV predicts cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality.[^10]

Practical HRV tracking:

Several consumer devices now offer HRV tracking: Apple Watch, Oura Ring, Fitbit, and Garmin devices all provide HRV metrics. As a coach, you're not diagnosing anything with HRV data, but you can help clients:

- Establish a personal baseline over 1-2 weeks

- Notice trends (Is HRV declining during high-stress periods? Improving with recovery practices?)

- Use data to inform recovery timing (Train hard when HRV is high; prioritize recovery when it's low)

- Avoid "orthosomnia". Don't let tracking create anxiety that defeats the purpose

HRV biofeedback is a more structured approach where clients learn to voluntarily increase HRV through slow breathing at approximately 6 breaths per minute. Research shows this can reduce blood pressure by 4-5 mmHg in people with hypertension, a clinically meaningful change.[^11]

The stress cycle: Completion matters¶

This concept comes from the work of Emily and Amelia Nagoski: stress needs to complete, not just stop. When a stressor ends, your body still has stress hormones circulating. The stress response was designed to be followed by action: running, fighting, physically resolving the threat.

In modern life, stressors often don't have physical resolutions. The difficult email doesn't get resolved by running. The work deadline doesn't end with a fight. But your body still needs to complete the stress cycle to return to baseline.

Ways to complete the stress cycle:

- Physical movement: The most direct method, even a brief walk or some stretching helps

- Breathing: Deep, slow breaths signal safety to your nervous system

- Social connection: Positive interaction with safe people (even brief) completes stress responses

- Laughter: Genuine laughter involves physical release

- Crying: Sometimes emotional expression is what the body needs

- Creative expression: Making music, art, or writing can process stress

This isn't abstract. Helping clients build habits that complete stress cycles is concrete, actionable coaching. "How did you discharge that work stress before you got home?" is a powerful question.

Coaching in Practice: "What's This HRV Thing?"¶

Client: "My watch keeps showing me HRV numbers. I have no idea what they mean or why I should care."

Coach: "Think of HRV as your battery indicator for recovery. Just like you wouldn't run your phone to 1% every day and expect it to perform well, your body has recovery reserves. HRV gives you a rough sense of where that battery stands."

Client: "So a higher number is better?"

Coach: "Generally, yes. But don't obsess over daily numbers. What's useful is noticing patterns. Does your HRV drop after poor sleep? After heavy drinking? Does it rise after rest days? That pattern recognition helps you make better decisions about training and recovery."

Client: "It feels like one more thing to track."

Coach: "If tracking creates more stress than insight, skip it. You can absolutely manage stress without a wearable. But for people who like data, HRV can show you that your recovery practices are actually working. It's optional, not required."

[CHONK: Section 3 - Parasympathetic Activation Practices]

Parasympathetic activation practices: Training your recovery system¶

Meditation for longevity¶

Meditation isn't just relaxation. It's a trainable skill that produces measurable changes in brain structure and stress physiology. Two approaches have substantial research support for stress reduction and health outcomes.

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR)

MBSR is an 8-week structured program developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn that combines mindfulness meditation, body awareness, and gentle yoga. It's perhaps the most researched meditation intervention in clinical settings.

What the evidence shows:

- MBSR was found to be noninferior to escitalopram (a common SSRI medication) for anxiety disorders in a randomized controlled trial, meaning it worked as well as the drug.[^12]

- Systematic reviews show consistent benefits for stress, anxiety, depression, and pain outcomes

- The 8-week structure appears important; shorter interventions show weaker effects

- Effects persist beyond the training period with continued practice

MBSR involves formal practices (45-minute daily meditation) plus informal mindfulness applied to daily activities. The time commitment is substantial, which is both a limitation and part of what makes it effective.

Transcendental Meditation (TM)

TM is a mantra-based meditation technique where practitioners silently repeat a specific sound or phrase. It's taught through certified instructors in a standardized format.

What the evidence shows:

- Meta-analyses show significant reductions in anxiety, comparable to other meditation forms

- A 2012 trial in African Americans with coronary heart disease found 48 percent reduction in major adverse cardiac events with TM practice[^13]

- Some mortality studies show approximately 23 percent reduction in all-cause mortality with TM practice, though study quality varies[^14]

- The 20-minute twice-daily protocol is well-defined and relatively easy to follow

Important context for both approaches:

Both MBSR and TM have meaningful evidence behind them. The "best" choice depends on client preferences:

- Clients who prefer structured learning and guidance may do well with MBSR's course format

- Clients who want a simple, repeatable technique may prefer TM's mantra approach

- Clients resistant to anything that feels "spiritual" may respond better to MBSR's secular framing

- Cost and access differ: TM requires paid instruction; MBSR courses vary but are often available through healthcare systems

As a coach, you're not teaching meditation. You're supporting clients in establishing and maintaining a practice. This might mean helping them find local MBSR courses, connecting them with meditation apps for guided practice, or simply problem-solving the barriers that keep meditation from becoming consistent.

Practical recommendations:

- Start simple: Even 10 minutes daily produces benefits; don't let "perfect" be the enemy of "good"

- Consistency matters more than duration: 10 minutes every day beats 45 minutes twice a week

- Set realistic expectations: Benefits accumulate over weeks; don't expect immediate transformation

- Address barriers directly: When, where, how will the client actually practice?

Breathwork: The direct vagal access point¶

Breathing is unique among autonomic functions. It happens automatically but can also be consciously controlled. This gives you direct access to the parasympathetic nervous system. Slow, controlled breathing activates the vagus nerve and shifts your body toward recovery mode.

What the research shows:

A meta-analysis of breathwork interventions found a moderate effect size (g = -0.35) for stress reduction.[^15] That's meaningful, comparable to many pharmaceutical interventions for stress and anxiety.

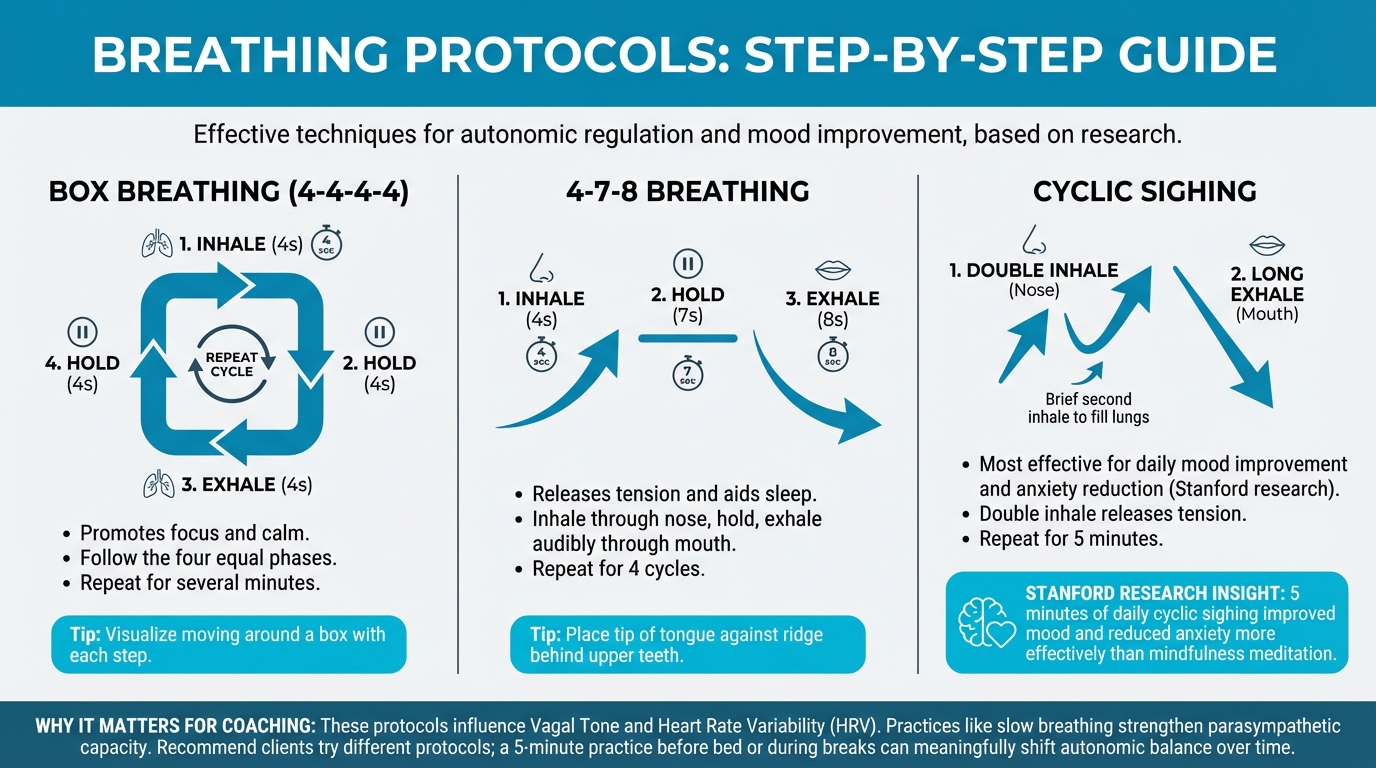

Key breathwork protocols:

Box breathing (4-4-4-4):

- Inhale for 4 seconds

- Hold for 4 seconds

- Exhale for 4 seconds

- Hold for 4 seconds

- Repeat

Figure: Box breathing, 4-7-8, cyclic sighing patterns

This protocol is used by military and first responders for acute stress management. It's simple to remember and can be done anywhere.

4-7-8 breathing:

- Inhale for 4 seconds

- Hold for 7 seconds

- Exhale for 8 seconds

- Repeat

The extended exhale phase particularly activates parasympathetic responses. This is often used as a sleep aid.

Cyclic sighing:

- Inhale through nose

- Second brief inhale to fully fill lungs

- Long exhale through mouth

- Repeat

Stanford research found that 5 minutes of cyclic sighing daily improved mood and reduced anxiety more effectively than mindfulness meditation in head-to-head comparison.[^16] The double-inhale technique appears to be especially effective for releasing tension.

Coherent breathing (~5.5 breaths/minute):

- Inhale for approximately 5.5 seconds

- Exhale for approximately 5.5 seconds

- No holds

This rate appears to optimize heart rate variability for many people. HRV biofeedback typically trains people toward this approximate rate.

Practical implementation:

Breathwork has advantages over meditation for some clients:

- Lower barrier to entry (no apps, courses, or instruction required)

- Can be done in almost any setting

- Immediate, noticeable effects

- Easy to remember specific protocols

- Less resistance from clients who don't identify with "meditation"

Recommend clients try different protocols and notice what resonates. A 5-minute breathing practice before bed or during work breaks can meaningfully shift autonomic balance over time.

| For DIY Learners |

|---|

| Applying this to yourself: Try "physiological sighing" right now: Double inhale through your nose (inhale, then sneak in a second smaller inhale), then long exhale through your mouth. Repeat 3 times. Notice how you feel. This simple technique, validated by Stanford research, can shift your nervous system toward calm in under a minute. Consider adding 5 cycles before bed or whenever stress spikes. |

Nature exposure: The 20-minute prescription¶

Time in natural environments—whether forests, parks, or even viewing nature through a window—reduces stress through multiple pathways.

What the research shows:

- Forest bathing (Shinrin-yoku) significantly reduces salivary cortisol. One study showed drops from 5.2 μg/dL to 2.77 μg/dL after two days of guided forest immersion[^17]

- HRV increases after nature exposure, indicating enhanced parasympathetic activity (approximately 9.7 ms increase in one study)[^17]

- Meta-analyses confirm small-to-moderate reductions in physiological stress markers (heart rate, blood pressure, cortisol) in natural versus urban environments[^18]

- Population studies link residential greenness to lower cardiovascular mortality, approximately 6 percent lower CVD mortality per quartile increase in neighborhood green space[^19]

- Each 10 percent increase in local green space coverage is associated with lower depression odds (OR ≈ 0.96)[^20]

Mechanisms likely involved:

- Attention restoration: Natural environments allow "soft fascination" that rests directed attention circuits

- Reduced sensory stress: Lower noise, fewer demands, less visual clutter

- Air quality: Forests produce phytoncides (plant chemicals) that may have immune and mood effects

- Physical activity: Natural settings encourage walking and movement

- Light exposure: Outdoor time provides natural light that supports circadian rhythms

Practical nature prescriptions:

Research suggests benefits accrue from relatively brief exposures: 20 minutes is a commonly cited threshold for measurable cortisol reduction, though longer is better when possible.[^21]

- The 20-minute walk: A daily walk in a park, greenway, or tree-lined area

- Forest bathing sessions: Longer immersive experiences (1-2 hours) when available

- Window views: Even visual exposure to nature through windows or images has some effect

- Indoor plants: Modest benefits for air quality and psychological wellbeing

- Urban alternatives: City parks, botanical gardens, waterfronts, tree-lined streets

For clients without easy nature access, research suggests that high-quality virtual nature (videos, VR) can provide some stress-relief benefits in the short term, though real nature remains the gold standard when available.[^22]

Movement as stress medicine¶

Chapter 2.9 established exercise as the most powerful longevity intervention. Here we emphasize a specific aspect: exercise is also stress medicine.

The BDNF connection:

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a protein that supports neuron growth, synaptic plasticity, and brain health. Think of it as fertilizer for your brain.

- Chronic stress and elevated cortisol suppress BDNF, contributing to cognitive decline[^23]

- Exercise increases BDNF, supporting neuroplasticity and resilience. Physically active individuals have 28 percent lower dementia risk and 45 percent lower Alzheimer's disease risk[^24]

- Mind-body practices (meditation, yoga) also increase BDNF while reducing cortisol[^25]

This creates a powerful stress-resilience connection: practices that reduce stress and increase BDNF simultaneously protect both mental and cognitive health.

Low-intensity cardio for recovery:

While high-intensity exercise has many benefits, it also creates stress that requires recovery. For stress management, low-intensity cardio has advantages:

- Activates parasympathetic system during and after exercise

- Counts as stress cycle completion

- Doesn't add significant recovery burden

- Zone 2 cardio (conversational pace) fits this category

Recommend clients include some low-intensity movement specifically framed as recovery, not just fitness.

Coaching in Practice: "I Tried Meditating But I Can't Stop Thinking"¶

Client: "I tried meditating a few times, but I couldn't stop thinking. My mind just races. I don't think it works for me."

Coach: "That's not failure. That's actually the practice."

Client: "What do you mean?"

Coach: "Meditation isn't about having no thoughts—it's about noticing when your mind wanders and gently returning your attention. Every time you notice you've wandered and come back, you're training your brain. That IS the workout."

Client: "But it feels like I'm doing it wrong."

Coach: "Think of it like going to the gym. You don't pick up a weight once and wonder why you're not stronger. The repetitions are the work. In meditation, the repetitions are: think, notice you're thinking, return to breath. Think, notice, return. That's the workout."

Client: "I guess I was expecting to feel peaceful right away."

Coach: "Start with 5 minutes. If that feels impossible, start with 2. The goal isn't to feel like a monk—it's to practice the skill of noticing where your attention is. The peaceful part comes later, with practice."

[CHONK: Section 4 - Building Resilience for Longevity]

Building resilience for longevity¶

Psychological resilience: The mortality connection¶

Resilience is more than a personality trait. It's a skill that can be developed, and it independently predicts longevity.

What the research shows:

In large cohort studies, higher psychological resilience is associated with 20-35 percent lower mortality per standard deviation increase in resilience scores.[^26] This effect persists even after controlling for health behaviors, socioeconomic factors, and baseline health status.

Key components of psychological resilience:

- Emotion regulation: The ability to manage emotional responses to stress without being overwhelmed

- Self-control: Capacity for delayed gratification and impulse management

- Optimism: Positive expectations about future outcomes

- Sense of purpose: Feeling that life has meaning and direction

- Social connectedness: Quality relationships that provide support

Each of these components is modifiable through intentional practice. Coaching can directly support emotion regulation skills, help clients clarify purpose, and facilitate social connection.

Growth mindset and aging perceptions¶

Your beliefs about aging and about stress itself affect your longevity.

Positive self-perceptions of aging:

In a landmark study by Becca Levy, older adults with positive self-perceptions of aging lived an average of 7.5 years longer than those with negative views, after controlling for health, socioeconomic status, and other factors.[^27] Related research shows that people with high "aging satisfaction" have 43 percent lower mortality.[^28]

This isn't just correlation. Experimental studies show that exposing people to positive aging stereotypes improves physical performance. Negative stereotypes worsen it. Your beliefs about aging literally affect your biology.

Stress mindset:

Here's a statistic that should reshape how you talk about stress: people who believe stress is harmful have 43 percent higher mortality when experiencing high stress. People who experience the same high stress but don't believe it's harmful? No increased mortality risk.[^29]

This doesn't mean stress is harmless. Chronic stress clearly has biological effects. But your interpretation of stress modulates those effects. Viewing stress as a challenge that mobilizes resources (rather than a threat that damages you) appears protective.

Coaching implications:

You can directly influence clients' mindsets:

- Help clients reframe stress responses: "Your heart is racing because your body is preparing you to meet this challenge"

- Challenge negative aging narratives: "What evidence contradicts that belief?"

- Focus on capability and growth rather than decline and limitation

- Model positive aging yourself in how you talk about the future

Social connection: The longevity multiplier¶

Social relationships aren't just pleasant. They're biological necessities. Humans evolved in social groups, and our physiology reflects that.

The mortality data:

- Social isolation increases mortality risk by 32 percent[^30]

- Loneliness (the subjective feeling of being alone, regardless of actual contact) increases mortality by 14 percent[^30]

- Sense of purpose in life reduces mortality by 15 percent per standard deviation increase[^31]

These are large effects, comparable to well-established risk factors like smoking and obesity.

Why social connection is physiologically protective:

- Reduces cortisol and stress reactivity

- Increases oxytocin (bonding hormone with stress-buffering effects)

- Provides practical support during illness or difficulty

- Encourages healthier behaviors (social influence)

- Provides sense of meaning and purpose

Building social resilience in clients:

Social connection is within coaching scope. You can:

- Help clients identify relationships they want to prioritize

- Problem-solve barriers to social engagement

- Encourage group activities (exercise classes, clubs, volunteering)

- Address social anxiety that limits connection

- Recommend professional support when social difficulties stem from deeper issues

Daily self-regulating practices¶

Research on longevity consistently shows that people who engage in daily self-regulating activities have better outcomes. These are simple practices that help manage stress, process emotions, and maintain psychological equilibrium.

Evidence-based daily practices:

Journaling:

- Expressive writing (writing about stressful experiences) improves physical and psychological health[^32]

- Gratitude journaling shifts attention toward positive experiences

- Even brief daily writing (10-15 minutes) produces benefits

Gratitude practice:

- Regular gratitude practice is associated with lower cortisol and better sleep

- Can be as simple as noting three good things each day

- Works partly by shifting attentional focus from threats to resources

Morning and evening routines:

- Consistent routines reduce decision fatigue and create structure

- Morning routines can include parasympathetic practices (breathwork, light exposure)

- Evening routines support sleep transition (reducing screens, relaxation practices)

Work-life boundaries:

- The longevity protocol recommends 8-hour maximum workdays

- Recovery requires genuine disconnection from work

- Physical and temporal boundaries help (no email after certain hour, dedicated workspace)

Coaching in Practice: The Overworked Executive¶

Client: "I know I need to manage my stress better, but I'm already working 60-hour weeks. I don't have time for another thing on my plate."

Coach: "Exactly. Adding a 30-minute meditation practice right now would probably just create more stress. You don't have margin."

Client: "So what am I supposed to do?"

Coach: "Let's think about this differently. What's one thing you could subtract that would reduce your stress load?"

Client: "I don't know... everything feels essential."

Coach: "Okay, what about a substitution? Like a 5-minute breathing practice instead of scrolling news during your morning coffee. Same time, different activity."

Client: "I could probably do that."

Coach: "For someone in your position, stress management isn't about adding practices—at least not initially. It's about creating any margin at all. That might mean delegating something at work, setting a boundary on evening email, or protecting your sleep. What feels most doable?"

[CHONK: Section 5 - Scope of Practice and Mental Health Referrals (CRITICAL)]

[CHONK: Section 5 - Scope of Practice and Mental Health Referrals (CRITICAL)]

Scope of practice and mental health referrals¶

This is the most important section of this chapter¶

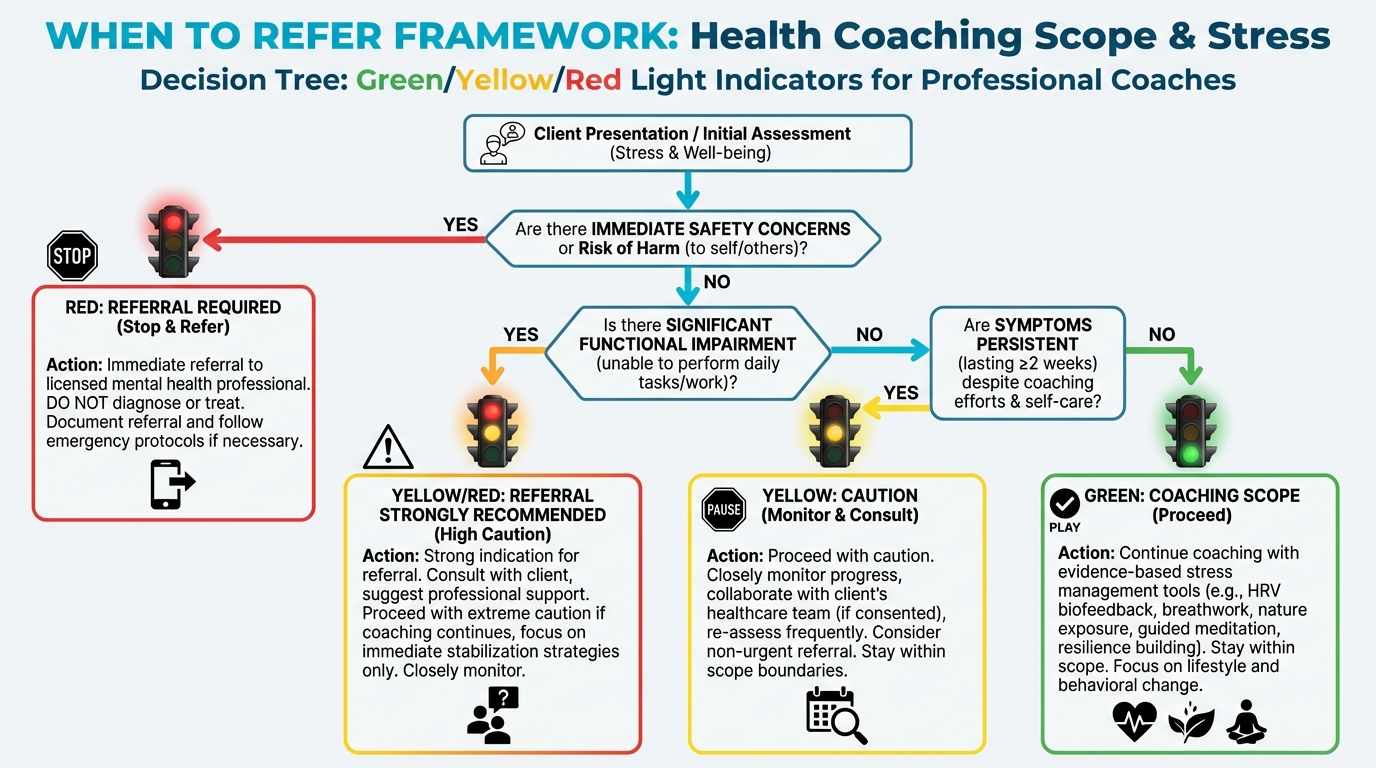

Everything we've discussed so far, stress physiology, parasympathetic practices, resilience building, is within coaching scope when applied to general wellness. But stress and mental health exist on a spectrum, and some presentations cross the line into clinical territory that requires licensed professionals.

Getting this boundary right protects your clients, protects you, and ensures people get the help they actually need. Please read this section carefully.

What coaches do and don't do¶

Coaches DO:

- Educate about stress physiology and its health effects

- Support healthy lifestyle practices (sleep, nutrition, movement, social connection)

- Help clients build habits and overcome barriers

- Provide accountability and motivation

- Support clients in following treatment plans designed by their healthcare team

- Help clients process normal life stress through conversation and problem-solving

- Refer when appropriate

Coaches DO NOT:

- Diagnose mental health conditions (depression, anxiety disorders, PTSD, etc.)

- Treat mental health conditions

- Provide therapy (CBT, DBT, EMDR, or any other therapeutic modality)

- Continue working with clients who need clinical-level care without appropriate referral

- Provide crisis intervention beyond immediate safety and connecting to resources

This isn't about your skills or intentions. It's about scope of practice, legal liability, and what's best for clients. A client with major depression needs treatment, not coaching, and a client with active suicidal ideation needs crisis intervention, not a meditation recommendation.

Recognizing when to refer¶

Some situations require immediate action, while others require prompt referral for evaluation—and here's how to tell the difference.

URGENT/EMERGENCY: Take immediate action:

- Suicidal ideation with plan or intent

- Self-harm behaviors

- Psychotic symptoms (hallucinations, delusions, severe disorganization)

- Severe agitation or aggression

- Medical emergencies (chest pain, signs of stroke, etc.)

What to do: Do not leave the client alone. Call 988 (Suicide & Crisis Lifeline) or 911 depending on severity. Document what happened. Follow up to ensure the client connected with appropriate care.

PROMPT REFERRAL: Within days:

- Depressive symptoms lasting ≥2 weeks (sad mood, loss of interest, sleep/appetite changes, fatigue, hopelessness)

- Anxiety that significantly impairs daily functioning

- Panic attacks

- Suspected eating disorder

- Substance use that's interfering with functioning

- Trauma history that's affecting current functioning

- Grief that isn't resolving normally

- Any mention of self-harm, even without current intent

What to do: Express concern. Recommend evaluation by a mental health professional. Offer to help them find resources. Be clear that coaching can continue alongside clinical care for appropriate clients, but that evaluation is needed.

CONTINUE WITH AWARENESS:

- Normal life stress with intact coping

- Mild, time-limited mood fluctuations

- Grief following a loss (with normal progression)

- General desire to improve stress management

What to do: Continue coaching with attention to any changes that might indicate worsening.

The 988 and 911 protocols¶

Every coach should know these resources:

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline:

- Call or text 988 (in the US)

- Chat available at 988lifeline.org

- Available 24/7

- For suicidal crisis, emotional distress, or when you're worried about someone

- Veterans can press 1 for the Veterans Crisis Line

911:

- Medical emergencies

- Imminent danger to self or others

- When someone is actively attempting self-harm

- When professional emergency response is needed

The "suicide mention" scenario¶

This deserves special attention. If a client mentions suicide, even casually, you need to respond.

What to say:

"I want to make sure I understand what you just said. When you mentioned [suicide/not wanting to be here/ending it], can you tell me more about what you mean?"

Listen, and don't panic. Most mentions of suicide are expressions of distress, not immediate danger. But you need to clarify.

Questions to ask:

- "Are you having thoughts of hurting yourself?"

- "Have you thought about how you would do it?"

- "Do you have access to [method mentioned]?"

- "Have you ever attempted suicide before?"

What to do based on answers:

- Passive ideation without plan: "I hear that you're really struggling. I'm not a mental health professional, but I want to make sure you get the right support. Would you be willing to talk to someone who specializes in this? I can help you find a therapist, or we can call 988 together right now."

- Active ideation with plan: "I'm really glad you told me. I'm concerned about your safety, and I want to stay with you while we get you connected to someone who can help. Let's call 988 together right now."

- Imminent danger: Stay with them. Call 911 if they're in immediate danger.

Document everything. After any mention of suicide, document what was said, what you asked, what the client answered, what action you took, and what follow-up is planned.

Working alongside mental health professionals¶

Coaching and therapy serve different purposes and can work together effectively.

When collaboration makes sense:

- Client is in therapy for a clinical issue but wants coaching support for health behaviors

- Client has stable mental health history with ongoing medication management

- Therapist specifically supports coaching as part of treatment plan

How to collaborate:

- With client consent, communicate with their treatment team

- Be clear about your role (coach, not therapist)

- Stay in your lane: support behavior change, not psychological treatment

- If coaching sessions repeatedly become therapy-like, redirect or refer

- Defer to clinical judgment on mental health matters

When coaching isn't appropriate:

- Active, untreated major mental illness

- Eating disorder without treatment team involvement

- Active substance use disorder without treatment

- Acute crisis state

- Client who refuses needed referral

Coaching in Practice: "My Client Seems Depressed"¶

You notice a client has low energy, seems sad, and mentions not sleeping well. They say they've "just been feeling really down lately."

Coach: "I've noticed you seem really low lately, and I'm a bit concerned. Can you tell me more about what's going on?"

Client: "I don't know. I'm just tired all the time. Nothing feels good anymore."

Coach: "How long have you been feeling this way?"

Client: "Maybe a month? I can't really remember when it started."

Coach: "And is it affecting your daily life—work, relationships, things you used to enjoy?"

Client: "Yeah. I used to love hiking, but I haven't gone in weeks. I just can't make myself do it."

Coach: "It sounds like this has been going on for a few weeks and is really affecting your life. I care about you, and I want to make sure you're getting the right support. Have you thought about talking to a therapist or your doctor about this?"

Client: "I don't know. It feels like such a big step."

Coach: "I understand. But what you're describing sounds like more than just stress that coaching can address. Would you be open to at least having a conversation with someone? I can help you find options."

If they agree: Help them find resources. Follow up to make sure they connected.

If they refuse: Document your concern and recommendation. Continue to monitor. Gently revisit if symptoms worsen. You cannot force someone to get help, but you can maintain the recommendation.

Deep health integration: Stress across all dimensions¶

Stress isn't just mental. It affects every dimension of health. The Deep Health framework helps you see these connections and coach accordingly.

Physical:

- Chronic stress impairs immune function, increases inflammation, disrupts sleep

- Intervention: Movement, sleep optimization, nutrition support

Mental-cognitive:

- Stress impairs concentration, memory, decision-making

- Chronic stress reduces BDNF and neuroplasticity

- Intervention: Cognitive practices, exercise (BDNF-boosting), stress management

Emotional:

- Stress amplifies negative emotions, reduces emotional regulation capacity

- Intervention: Emotional processing practices, breathwork, social support

Existential:

- Chronic stress can erode sense of meaning and purpose

- Purpose and meaning are protective against stress effects

- Intervention: Values clarification, purpose exploration, meaningful activities

Relational-social:

- Stress strains relationships; isolation worsens stress

- Social connection is powerfully protective

- Intervention: Prioritize relationships, address social barriers, community connection

Environmental:

- Physical environment can increase or reduce stress

- Nature access, noise, air quality all matter

- Intervention: Environmental optimization where possible, nature exposure

Comprehensive case study: Sarah¶

Background:

Sarah is a 52-year-old healthcare administrator. She came to coaching wanting to "get healthier" and mentioned feeling exhausted all the time. In your initial conversations, you learn:

- She works 55-60 hours per week and checks email constantly, including before bed

- Her sleep has been poor for "as long as she can remember." Takes an hour to fall asleep, wakes multiple times

- She hasn't exercised regularly in years; "no time"

- She describes herself as constantly stressed but says "everyone is stressed, it's just life"

- She has high blood pressure controlled with medication

- She lives with her husband and has two adult children who've moved out

- She used to enjoy gardening and reading but hasn't done either in over a year

- She mentions feeling "kind of empty" now that her kids are gone

Assessment (non-clinical):

Looking at Sarah through the Deep Health lens:

- Physical: Poor sleep, sedentary, high blood pressure, chronic fatigue

- Mental-cognitive: Likely impaired by chronic stress and poor sleep

- Emotional: Appears to be coping but mentions emptiness

- Existential: Loss of purpose since children left; abandoned previous meaningful activities

- Relational-social: Strong marriage, but limited social activity outside work

- Environmental: High-stress work environment; home sounds okay

Red flags to monitor:

The "emptiness" and abandoned activities warrant attention. These could indicate depression. You ask more:

"You mentioned feeling kind of empty since your kids left. Can you tell me more about that? Have you noticed other changes, like losing interest in things you used to enjoy, or feeling down or hopeless?"

Sarah says she does feel sad sometimes and misses her kids, but she doesn't feel hopeless and still enjoys things when she makes time for them (which is rare). This sounds more like adjustment to a life transition plus burnout than clinical depression. You'll stay alert.

Coaching approach:

Sarah doesn't need everything fixed at once. You collaboratively prioritize:

Week 1-4: Sleep foundation

- Establish consistent sleep/wake times (±30 minutes)

- No email after 8 PM (she negotiates to 9 PM, acceptable)

- 10 minutes of breathwork before bed (4-7-8 breathing)

- Goal: Fall asleep within 30 minutes, reduce night waking

Week 4-8: Add movement and recovery

- 20-minute daily walk (can be during lunch or after work)

- Reintroduce gardening on weekends: this serves multiple purposes (nature, meaningful activity, physical activity)

- One day per weekend completely work-free

Week 8-12: Build resilience practices

- Brief morning routine: 5-minute breathing, light exposure, no phone for first 30 minutes

- Gratitude practice: Three good things at dinner with husband

- Explore what "purpose" looks like in this life phase

Ongoing:

- Monitor for worsening mood; revisit referral question if needed

- Support medication adherence; encourage regular physician check-ins

- Continue building stress management capacity

What you notice:

By week 6, Sarah reports sleeping better and feeling less exhausted. She's walking most days and says she "forgot how much I like being outside." The evening email boundary was hard at first but now she protects it. By week 10, she's started gardening again and says she feels more like herself.

Her blood pressure at her last check-up was lower. Her doctor reduced her medication dose.

What this case illustrates:

- Stress management is foundational, not optional

- Start with fundamentals (sleep) before adding practices

- Frame activities to serve multiple purposes (walking = stress reduction + movement + nature exposure)

- Monitor for clinical issues while coaching within scope

- Progress compounds: better sleep → more energy → more capacity for other changes

- You didn't treat Sarah's blood pressure or empty nest syndrome, but coaching her on stress and lifestyle contributed to improvement in both

[CHONK: Study guide questions]

Study Guide Questions¶

Here are some questions that can help you think through the material and prepare for the chapter exam. They're optional, but we recommend you try answering at least a few as part of your active learning process.

-

What is allostatic load, and why does it matter for longevity?

-

Describe the difference between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. What does "sympathetic dominance" mean in practical terms?

-

What is heart rate variability (HRV), and what does higher HRV generally indicate?

-

Compare MBSR and TM. What evidence supports each, and how might you help a client choose?

-

What is the "stress cycle," and why does it need to complete? Name three ways to complete a stress cycle.

-

How does chronic stress affect BDNF, and why does this matter for brain health?

-

Describe the mortality associations for psychological resilience, positive aging beliefs, and social connection.

-

When should a coach refer a client to a mental health professional? List at least three situations that warrant prompt referral.

Self-reflection questions:

-

Rate your current stress level 1-10. What are the top 2-3 stressors in your life right now? Which ones can you change, and which ones require acceptance and coping strategies?

-

How do you currently complete your stress cycles? Do you have regular practices for "discharging" stress from your body?

Deep Dives¶

Want to go deeper? These supplemental articles explore key topics from this chapter in more detail.

- HRV Training Deep Dive: Protocols and interpretation

- Meditation Modalities. MBSR vs. TM vs. Other approaches

References¶

-

Deng Q, et al.. Social stress and mortality among older adults in China: A longitudinal study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr; 2025. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40795324/

-

Schmalbach I, et al.. Within-person associations of cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone, and testosterone hair hormone concentrations and psychological distress. Psychoneuroendocrinology; 2023. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37928315/

-

Tsigos C, Chrousos GP. Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, neuroendocrine factors and stress. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53(4):865-871. doi:10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00429-4

-

Rohleder N. Stress and inflammation – The need to address the gap in the transition between acute and chronic stress effects. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;105:164-171. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.02.021

-

Epel ES, Blackburn EH, Lin J, Dhabhar FS, Adler NE, Morrow JD, et al. Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101(49):17312-17315. doi:10.1073/pnas.0407162101

-

Poganik JR, Zhang B, Baht GS, Kerepesi C, Yim SH, Lu AT, et al. Biological age is increased by stress and restored upon recovery. 2022. doi:10.1101/2022.05.04.490686

-

Guidi J, Lucente M, Sonino N, Fava GA. Allostatic Load and Its Impact on Health: A Systematic Review. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2020;90(1):11-27. doi:10.1159/000510696

-

Ribeiro AI, et al.. Lifestyle behaviors and allostatic load: A systematic review.. Prev Med; 2022. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35066347/

-

Gerritsen RJS, Band GPH. Breath of Life: The Respiratory Vagal Stimulation Model of Contemplative Activity. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2018;12. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00397

-

Thayer J, Lane R. The role of vagal function in the prevention of and risk for cardiovascular disease and mortality. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation. 2006;13(Supplement 1):S31. doi:10.1097/00149831-200605001-00124

-

Lopes S, et al.. Effects of stress management interventions on HRV in cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Behav Med; 2024. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38478157/

-

Hoge EA, Bui E, Mete M, Dutton MA, Baker AW, Simon NM. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction vs Escitalopram for the Treatment of Adults With Anxiety Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80(1):13. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.3679

-

Schneider RH, Grim CE, Rainforth MV, Kotchen T, Nidich SI, Gaylord-King C, et al. Stress Reduction in the Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2012;5(6):750-758. doi:10.1161/circoutcomes.112.967406

-

Anderson JW, Liu C, Kryscio RJ. Blood Pressure Response to Transcendental Meditation: A Meta-analysis. American Journal of Hypertension. 2008;21(3):310-316. doi:10.1038/ajh.2007.65

-

Sutar R, et al.. Efficacy of pranayama on perceived stress and anxiety: A meta-analysis. Int J Yoga; 2024. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40980898/

-

Balban MY, Neri E, Kogon MM, Weed L, Nouriani B, Jo B, et al. Brief structured respiration practices enhance mood and reduce physiological arousal. Cell Reports Medicine. 2023;4(1):100895. doi:10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100895

-

Queirolo L, Fazia T, Roccon A, Pistollato E, Gatti L, Bernardinelli L, et al. Effects of forest bathing (Shinrin-yoku) in stressed people. Frontiers in Psychology. 2024;15. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1458418

-

Gaekwad JS, Sal Moslehian A, Roös PB. A meta-analysis of physiological stress responses to natural environments: Biophilia and Stress Recovery Theory perspectives. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2023;90:102085. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.102085

-

Bianconi A, Longo G, Coa AA, Fiore M, Gori D. Impacts of Urban Green on Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Diseases—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023;20(11):5966. doi:10.3390/ijerph20115966

-

Zhang Y, et al.. Green space exposure on depression and anxiety outcomes: A meta-analysis. SSM Popul Health; 2023. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37268208/

-

Hunter MR, Gillespie BW, Chen SY. Urban Nature Experiences Reduce Stress in the Context of Daily Life Based on Salivary Biomarkers. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019;10. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00722

-

Fan L, Baharum MR. The effects of digital nature and actual nature on stress reduction: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Internet Interventions. 2024;38:100772. doi:10.1016/j.invent.2024.100772

-

Numakawa T, Kajihara R. Involvement of brain-derived neurotrophic factor signaling in the pathogenesis of stress-related brain diseases. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience. 2023;16. doi:10.3389/fnmol.2023.1247422

-

Lin T, Tsai S, Kuo Y. Physical Exercise Enhances Neuroplasticity and Delays Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Plasticity. 2018;4(1):95-110. doi:10.3233/bpl-180073

-

Puhlmann LM, Vrtička P, Linz R, Valk SL, Papassotiriou I, Chrousos GP, et al. Serum BDNF Increase After 9-Month Contemplative Mental Training Is Associated With Decreased Cortisol Secretion and Increased Dentate Gyrus Volume: Evidence From a Randomized Clinical Trial. Biological Psychiatry Global Open Science. 2025;5(2):100414. doi:10.1016/j.bpsgos.2024.100414

-

Zhang C, Bai A, Li W, Wang Q, Liu S, Miao M. Impact of change in psychological resilience on subsequent all-cause and cause-specific mortality in community-dwelling older adults: a nationwide cohort study. Public Health. 2025;246:105833. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2025.105833

-

Levy BR, Slade MD, Kunkel SR, Kasl SV. Longevity increased by positive self-perceptions of aging. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83(2):261-270. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.83.2.261

-

Stephan Y, Sutin AR, Terracciano A. Subjective Age and Mortality in Three Longitudinal Samples. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2018;80(7):659-664. doi:10.1097/psy.0000000000000613

-

Keller A, Litzelman K, Wisk LE, Maddox T, Cheng ER, Creswell PD, et al. Does the perception that stress affects health matter? The association with health and mortality. Health Psychology. 2012;31(5):677-684. doi:10.1037/a0026743

-

Holt-lunstad J, Smith T. Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-analytic Review. SciVee. 2010. doi:10.4016/19911.01

-

Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Meaning in life and mortality: UK Biobank study. Lancet Public Health; 2024. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39550820/

-

Pennebaker JW. Expressive Writing in Psychological Science. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2017;13(2):226-229. doi:10.1177/1745691617707315

Figure: Green/yellow/red light indicators