Unit 2: Core Interventions — The Protocol¶

Chapter 2.11: Sleep Optimization¶

1-Minute Summary¶

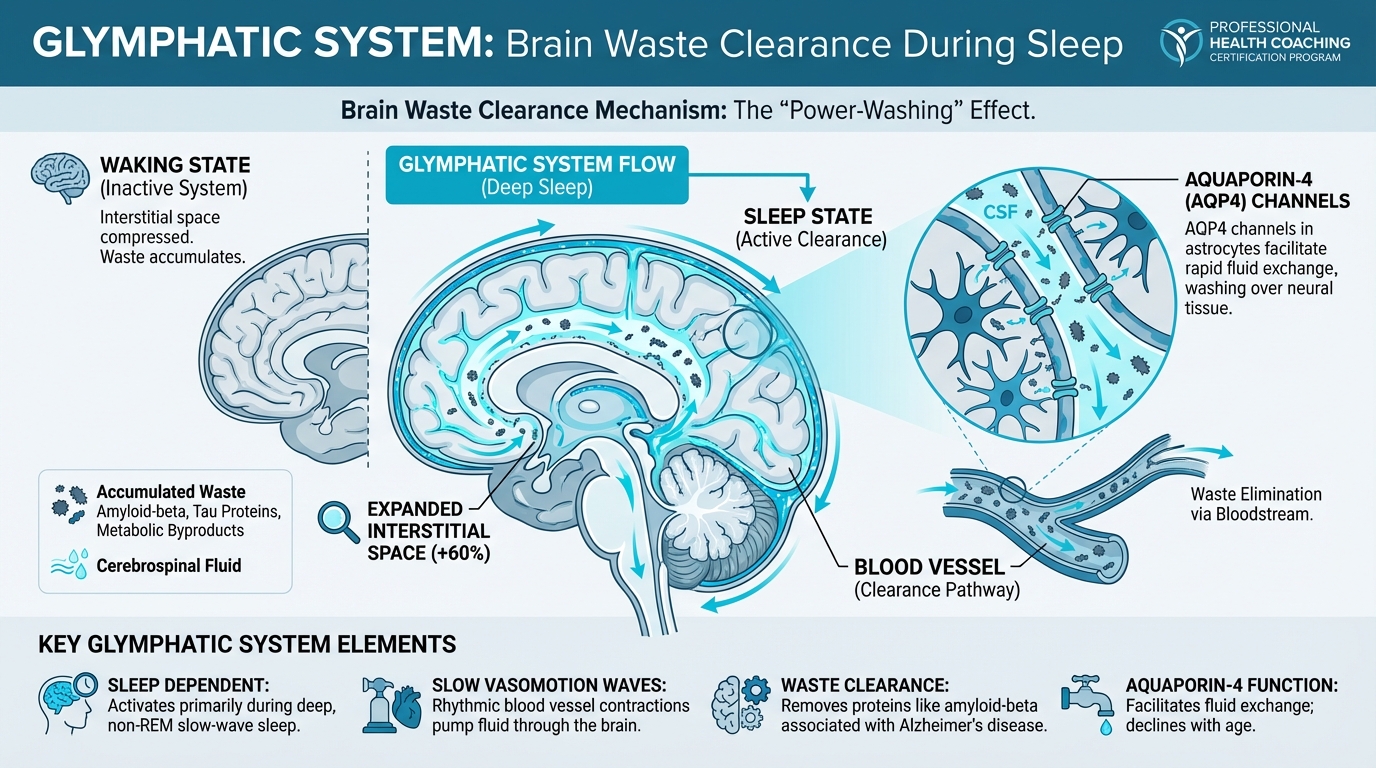

Sleep isn't rest. It's an active metabolic process that cleans your brain, consolidates memories, and repairs your body. During deep sleep, your brain's glymphatic system flushes out waste products like amyloid-beta, the protein associated with Alzheimer's disease. Sleep deprivation doesn't just make you tired; it raises mortality risk, impairs cognitive function, and accelerates biological aging.

Figure: Brain waste clearance during sleep

The evidence is clear: 7-8 hours of sleep is the sweet spot for longevity, with both shorter and longer durations associated with higher mortality. But here's what many people miss: consistency matters as much as duration. Sleeping the same times each night predicts longevity better than total hours.

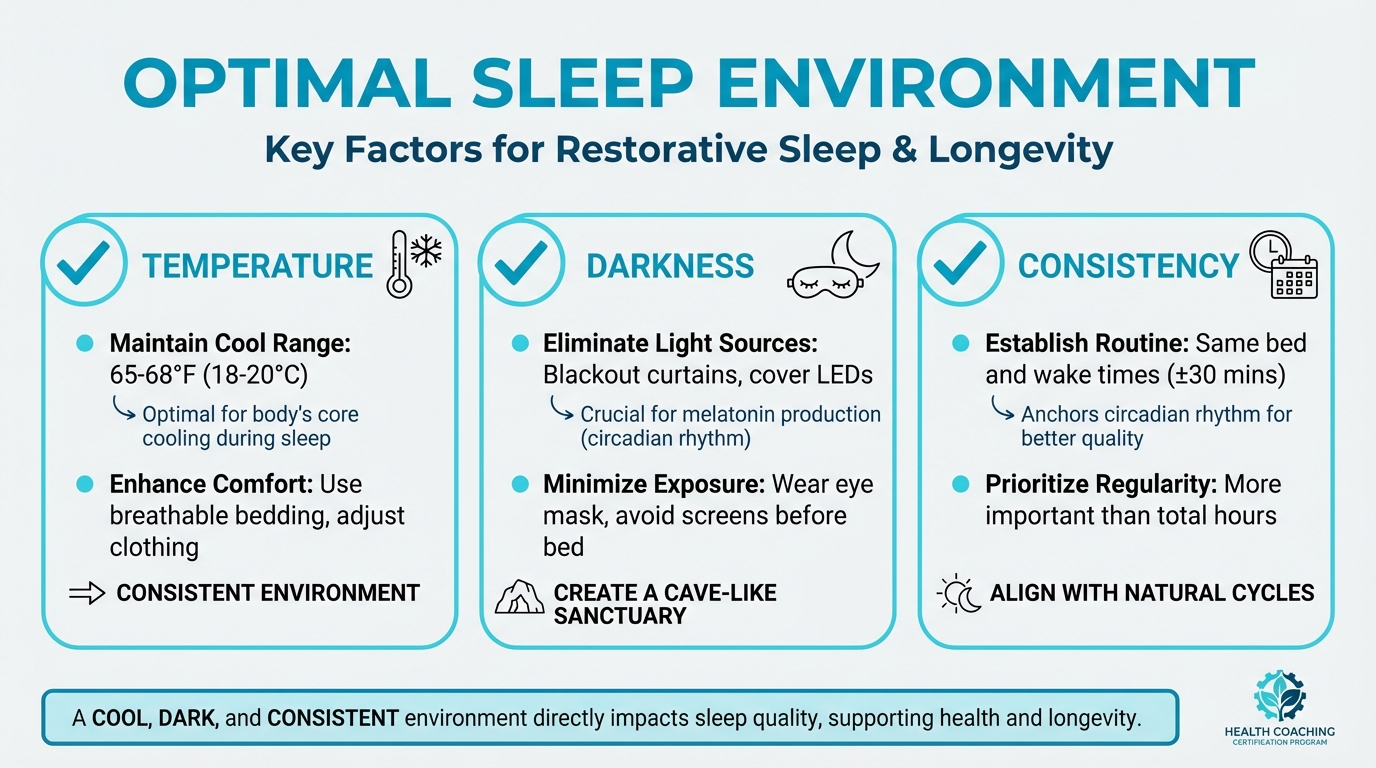

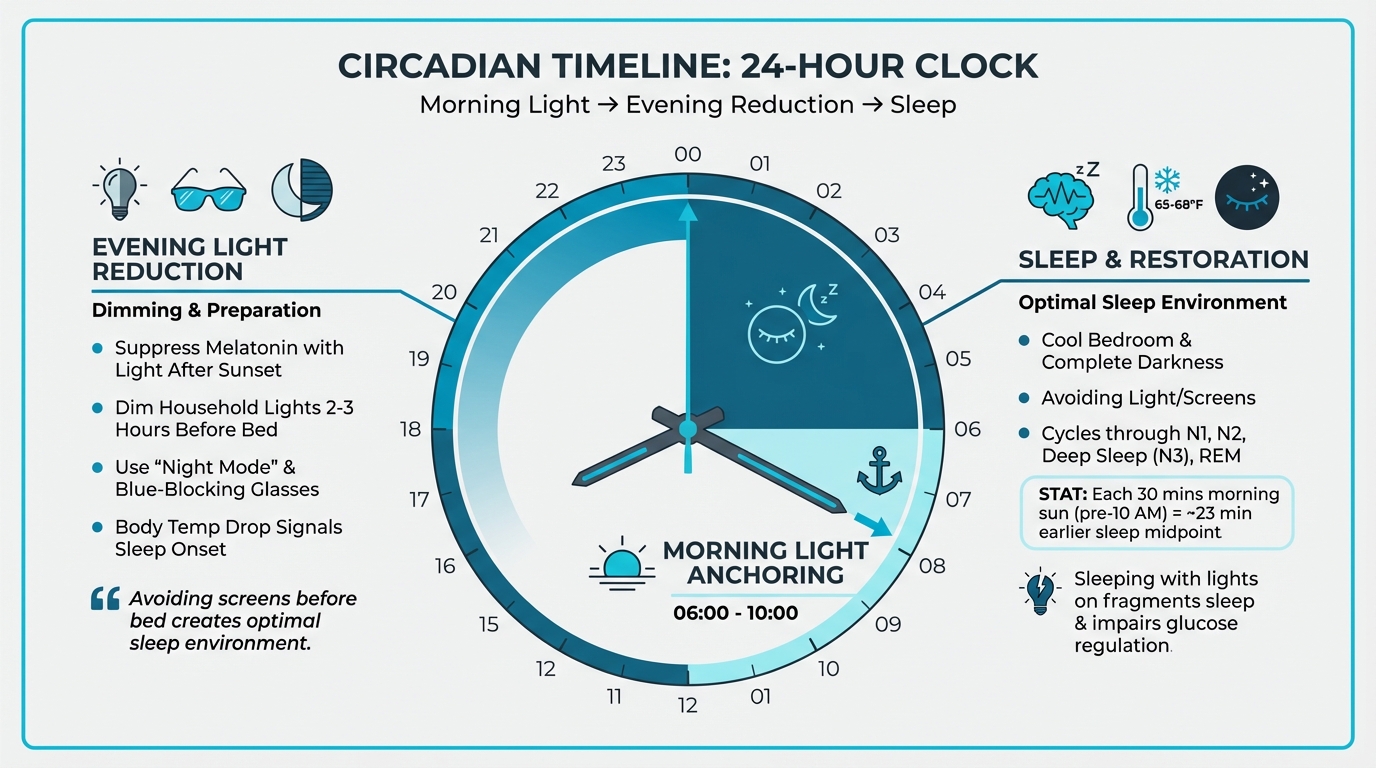

Your circadian rhythm—the body's 24-hour clock—responds powerfully to light. Morning sunlight within 30 minutes of waking anchors your rhythm and improves sleep quality that night. A cool bedroom (65-68°F), complete darkness, and avoiding screens before bed create the optimal sleep environment.

Figure: 65-68°F, darkness, consistency

For coaches, the biggest skill isn't teaching sleep hygiene. It's helping clients avoid orthosomnia, the anxiety that comes from obsessing over sleep scores. Sleep optimization should reduce stress, not add to it. Know when to refer out for potential sleep disorders, and help clients find a "good enough" approach that's sustainable.

[CHONK 1: Why Sleep is a Longevity Lever]¶

Sleep: An Active Metabolic Process¶

Most people think of sleep as "rest", a passive state where not much happens. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Sleep is one of the most metabolically active periods of your day. During sleep, your body releases growth hormone, repairs tissue, and consolidates memories. But perhaps the most fascinating discovery of the past decade involves what happens in your brain while you sleep: the glymphatic system activates, essentially power-washing your neural tissue of accumulated metabolic waste.[^1]

The glymphatic system is the brain's dedicated waste clearance network. During waking hours, neural activity produces metabolic byproducts, including proteins like amyloid-beta and tau, which are associated with Alzheimer's disease when they accumulate. The glymphatic system clears these toxins by circulating cerebrospinal fluid through channels alongside blood vessels, flushing waste into the bloodstream for elimination.[^2]

Here's what makes sleep critical: the interstitial space between neurons expands by roughly 60% during sleep, dramatically increasing the efficiency of this waste clearance. In mice, amyloid-beta is cleared approximately twice as fast during sleep compared to wakefulness.[^3]

What this means for your client: Every night of good sleep is an investment in long-term brain health. Poor sleep isn't just about feeling tired tomorrow. It's about allowing neurotoxic proteins to accumulate over years and decades.

The Glymphatic System: Your Brain's Cleaning Crew¶

The mechanism driving glymphatic function is elegant. During deep sleep (specifically, non-REM slow-wave sleep), synchronized waves of neural activity create a rhythmic pattern of blood vessel contractions. These slow vasomotion waves, coupled with oscillations in norepinephrine from the locus coeruleus, physically pump cerebrospinal fluid through the brain.[^4]

Think of it like waves washing over a beach, except instead of depositing debris, these waves are carrying it away.

The glymphatic system depends on aquaporin-4 (AQP4) channels in the cells that line blood vessels in the brain. These channels facilitate the fluid exchange that makes waste clearance possible. As we age, AQP4 function declines. This may partly explain why older adults are more vulnerable to neurodegenerative disease.[^5]

One important nuance: some sedative medications (like zolpidem) appear to suppress the norepinephrine oscillations that drive glymphatic flow, reducing clearance by more than 30%.[^6] This is why natural sleep is generally preferable to medicated sleep when possible, though clients with diagnosed sleep disorders should follow their physician's recommendations.

Growth Hormone and Recovery¶

Sleep is when your body repairs itself. Growth hormone (GH) release occurs primarily during the first few hours of sleep, concentrated in deep slow-wave sleep phases. GH stimulates tissue repair, muscle synthesis, and metabolic regulation.[^7]

This has profound implications for recovery from exercise, injury, and the daily wear of life. Athletes who sleep less than 7 hours show significantly impaired recovery markers compared to those sleeping 8+ hours. But this isn't just about athletes: anyone recovering from illness, managing chronic conditions, or simply trying to maintain physical function benefits from adequate sleep-based GH release.

Memory Consolidation: Learning While You Sleep¶

Sleep doesn't just clean your brain. It organizes it. During both deep sleep and REM sleep, memories are consolidated, transferring from short-term storage in the hippocampus to long-term storage in the cortex.[^8]

Sleep deprivation impairs the ability to form new memories and recall existing ones. In practical terms, that all-nighter before an exam is counterproductive. You'd learn more by sleeping and studying less.

Sleep Deprivation and Mortality Risk¶

The mortality data on sleep is remarkably consistent. A 2025 meta-analysis of 79 cohort studies found:[^9]

- Short sleep (<7 hours): 14% higher all-cause mortality risk (HR 1.14, 95% CI 1.10–1.18)

- Long sleep (≥9 hours): 34% higher all-cause mortality risk (HR 1.34, 95% CI 1.26–1.42)

The relationship is U-shaped, with the lowest mortality risk at 7-8 hours nightly. Both sleeping too little and sleeping too much are associated with increased risk, though the mechanisms differ. Short sleep likely causes harm directly, while long sleep often reflects underlying illness or poor sleep quality.

At the extremes, the risks are even more pronounced. Sleeping 5 hours or less, or 10 hours or more, dramatically elevates mortality risk: roughly 40-100% higher than optimal sleep duration.[^10]

Coaching in Practice: "I Function Fine on 6 Hours"¶

Client: "I've slept 6 hours a night for years. I function fine."

Coach: "You've clearly adapted to that schedule—many people do. But here's what the research shows: people often underestimate how much sleep affects them. It's like someone who's always lived in a noisy city not noticing the noise anymore."

Client: "So you're saying I'm not actually fine?"

Coach: "I'm saying there might be headroom you don't know you have. Most people notice clearer thinking, better mood, and more energy when they move toward 7-8 hours. Would you be open to a 2-week experiment? Try 7 hours and see how you feel."

Client: "I don't know if I have time for that."

Coach: "That's fair. But consider this: what if the hour you 'save' by sleeping less costs you two hours of productivity during the day? The research on sleep and cognitive performance is pretty striking. Might be worth testing."

[CHONK 2: The Science of Sleep Architecture]¶

The 90-Minute Sleep Cycle¶

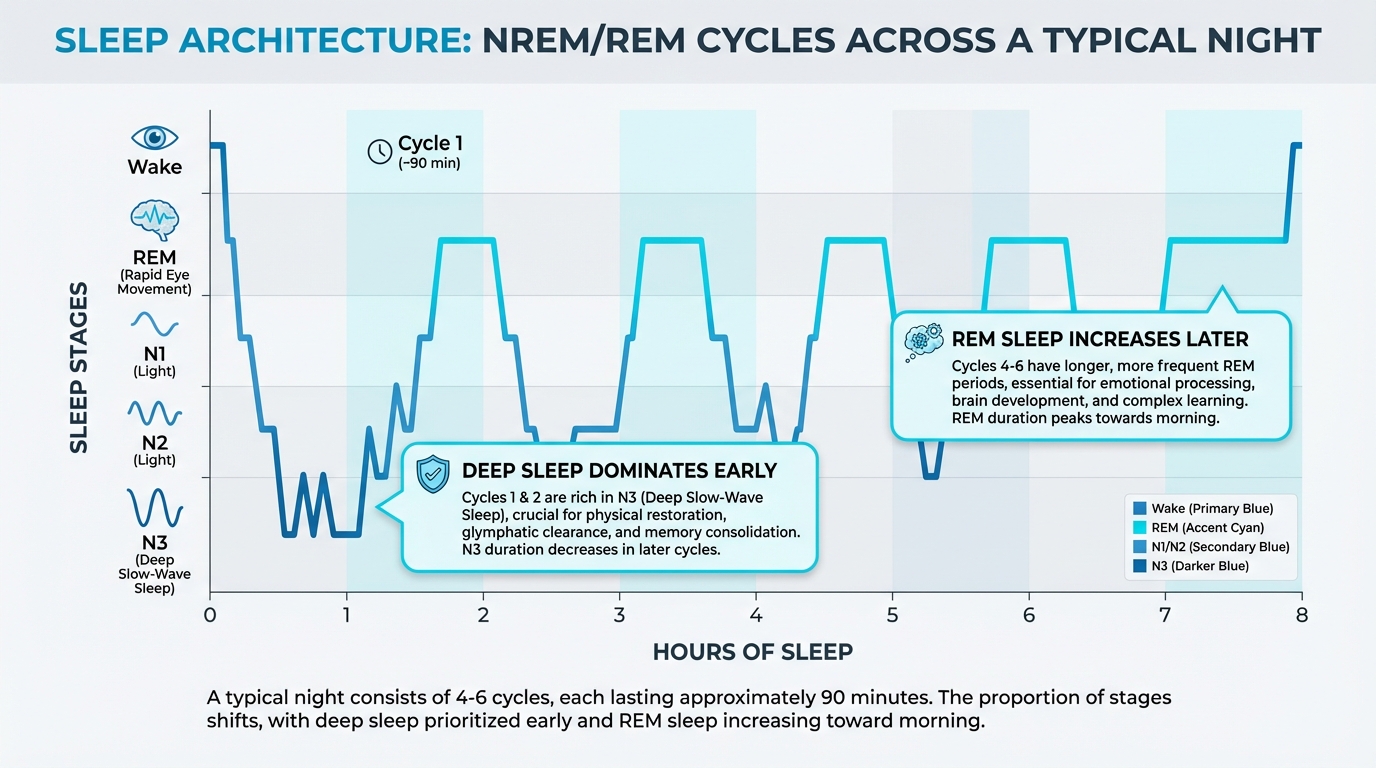

Sleep isn't a uniform state. It's a dynamic process that cycles through distinct stages approximately every 90 minutes throughout the night.

A typical night involves 4-6 of these cycles. Each cycle progresses through lighter sleep stages (N1, N2) into deep slow-wave sleep (N3), then into REM (rapid eye movement) sleep before the cycle repeats. The proportion of time spent in each stage shifts across the night: deep sleep dominates early cycles, while REM sleep increases toward morning.[^11]

Figure: NREM/REM cycles across night

Understanding this architecture helps explain why some sleep feels more restorative than others. Interrupting sleep during deep phases leaves people feeling groggy, while waking during lighter stages feels more natural.

For coaches wanting deeper coverage of sleep science, including detailed neurophysiology of sleep stages, Precision Nutrition's Level 1 Sleep, Stress Management, and Recovery Certification provides comprehensive training.

Deep Sleep: The Recovery Phase¶

Deep sleep (N3, also called slow-wave sleep) is the most physically restorative phase. This is when:

- The glymphatic system is most active, clearing brain waste[^12]

- Growth hormone release peaks

- Heart rate and blood pressure drop to their lowest levels

- The immune system strengthens

Deep sleep is characterized by slow, synchronized brain waves (delta waves). The stronger these waves, the more efficient glymphatic clearance appears to be. Human EEG slow-wave power correlates with greater cerebrospinal fluid tracer influx.[^13]

Adults typically spend 15-25% of sleep in deep stages, but this proportion declines with age. By age 60, deep sleep may represent only 5-10% of total sleep time.[^14]

REM Sleep: The Brain's Processing Time¶

REM sleep is when your brain consolidates emotional memories and processes complex information. It's also when most vivid dreaming occurs.

During REM, the body becomes temporarily paralyzed (sleep atonia), a protective mechanism that prevents us from acting out our dreams. Breakdown of this paralysis can indicate sleep disorders requiring medical evaluation.

REM sleep supports:[^15]

- Emotional regulation

- Creative problem-solving

- Procedural memory (learning skills)

- Neural plasticity

Like deep sleep, REM serves critical clearance functions. Recent wearable research suggests clearance signals occur across both deep and REM sleep stages.[^16]

How Sleep Architecture Changes with Age¶

Sleep architecture changes predictably across the lifespan:

- Young adults (18-30): More deep sleep, consolidated sleep periods

- Middle age (30-60): Gradual decline in deep sleep, more nighttime awakenings

- Older adults (60+): Less deep sleep, earlier sleep timing, more fragmented sleep

These changes are normal. They don't mean older adults need less sleep. Most adults continue to need 7-8 hours regardless of age. What changes is the effort required to achieve quality sleep and the tolerance for sleep disruption.[^17]

What this means for your client: Older clients may need more attention to sleep hygiene and environment to compensate for natural changes in sleep architecture. They're not "bad sleepers." They're working with different physiological constraints.

[CHONK 3: Circadian Rhythm Optimization]¶

What Is Your Circadian Rhythm?¶

Your circadian rhythm is a roughly 24-hour internal clock that regulates sleep-wake cycles, hormone release, body temperature, and dozens of other physiological processes. This rhythm is generated by a cluster of cells in the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN).[^18]

The circadian system doesn't run independently. It synchronizes to external cues called zeitgebers (German for "time-givers"). The most powerful zeitgeber is light.

Morning Light Anchoring: Within 30 Minutes of Waking¶

Morning light exposure is the single most effective intervention for circadian optimization. Light hitting the retina signals the SCN that it's daytime, advancing and stabilizing circadian timing.

The evidence is compelling:

- Each additional 30 minutes of morning sun (before 10 a.m.) is associated with a 23-minute earlier sleep midpoint and improved sleep quality[^19]

- Enhanced daylight access advanced sleep onset by approximately 22 minutes in controlled studies[^20]

- Outdoor morning light delivers vastly more circadian-relevant illumination than indoor lighting, about 3,000+ lux versus 300-500 lux indoors[^21]

Practical recommendation: Get bright light exposure, ideally natural sunlight, within 30 minutes of waking. Even 10-20 minutes makes a difference. On cloudy days, outdoor light is still far brighter than indoor light. If you can't get outside, consider a light therapy device (10,000 lux, used for 20-30 minutes at wake).[^22]

| For DIY Learners |

|---|

| Applying this to yourself: Before buying any sleep gadgets or supplements, try this free intervention for one week: Get outside within 30 minutes of waking for at least 10 minutes of natural light exposure. Morning coffee on the porch counts. A brief walk counts. Even on cloudy days, outdoor light is 10-30x brighter than indoor lighting. This single habit can advance your sleep timing by 20+ minutes and improve sleep quality. Track how you feel. |

Evening Light Reduction¶

Just as morning light advances circadian timing, evening light delays it. Light exposure after sunset tells the brain that it's still daytime, suppressing melatonin release and pushing sleep timing later.

Figure: Morning light → Evening reduction → Sleep

Blue-wavelength light (from screens and LED lighting) is particularly potent at suppressing melatonin. Strategies to reduce evening light exposure include:[^23]

- Dimming household lights 2-3 hours before bed

- Using "night mode" on devices (though this alone may not be sufficient)

- Wearing blue-blocking glasses in the evening

- Keeping the bedroom as dark as possible during sleep

Sleeping with lights on, even a TV in the background, fragments sleep, raises heart rate, and impairs morning glucose regulation.[^24]

Meal Timing and Circadian Rhythm¶

Food is a secondary zeitgeber. The timing of meals influences peripheral circadian clocks in the liver, gut, and other organs. Eating late at night can desynchronize these peripheral clocks from the central clock, contributing to metabolic dysfunction.[^25]

Protocol guidance: Finish your last substantial meal 2-3 hours before bedtime. This allows digestion to complete before sleep onset and supports circadian alignment.

Temperature Regulation Throughout the Day¶

Body temperature follows a circadian pattern, rising during the day and falling in the evening. This temperature drop is a signal for sleep onset.

Strategies that facilitate the evening temperature drop include:[^26]

- Keeping bedrooms cool (more on this in CHONK 4)

- Taking a warm bath 1-2 hours before bed (which paradoxically causes subsequent cooling)

- Avoiding vigorous exercise close to bedtime

Working with Shift Workers: An Extended Guide¶

Shift work presents one of the most challenging circadian disruptions. About 15-20% of workers in industrialized nations work non-standard hours, and the health consequences are significant: elevated cardiovascular disease risk, metabolic dysfunction, and substantially impaired sleep.[^27]

The fundamental challenge: Only about 25% of night-shift workers naturally adapt their circadian rhythm to align with their schedule, even after multiple consecutive night shifts.[^28] Most workers remain in a state of chronic circadian misalignment.

Health consequences of shift work:

- Night-shift work is associated with ~13% higher cardiovascular disease incidence and ~27% higher cardiovascular mortality[^29]

- Insomnia affects 29-38% of shift workers compared to ~6% of the general population[^30]

- Shift work sleep disorder (SWSD), characterized by excessive sleepiness and insomnia related to work schedules, affects about 30% of shift-working nurses[^31]

Light-Based Strategies for Shift Workers¶

Light is the most powerful tool for circadian adaptation, when used strategically.

During night shifts:

- Exposure to bright, blue-enriched light during the first half of the night shift can help delay circadian phase and improve alertness

- A 2025 meta-analysis found that timed light therapy increased total sleep time by ~32.5 minutes and sleep efficiency by ~2.9 percentage points[^32]

- Blue-enriched light (>5,000 K color temperature) is particularly effective at reducing sleepiness

After night shifts:

- Wear blue-blocking sunglasses during the morning commute home to avoid unintended phase advances[^33]

- Create a dark, cave-like sleep environment for daytime sleep

- Consider blackout curtains, eye masks, and white noise machines

On days off:

The question of whether to maintain the shifted schedule or revert to normal timing depends on work patterns. For workers on permanent night schedules, maintaining the shifted timing (sleeping during the day even on days off) may support better adaptation. For rotating schedules, strategies vary.

Sleep Scheduling Strategies¶

Consistent shift-type windows: Research shows that maintaining similar sleep windows for each type of shift reduces mid-shift sleepiness.[^34] For example:

- Day shift: Sleep 10 PM - 6 AM

- Night shift: Sleep 8 AM - 4 PM

- Transition days: Strategic napping

Sleep banking: Getting ≥9 hours of sleep the night before starting a stretch of night shifts is associated with better performance effectiveness during the week.[^35]

Strategic napping:

- Short naps (15-20 minutes) during breaks can boost alertness

- Longer naps (~90 minutes, completing one sleep cycle) provide more substantial recovery but may cause sleep inertia

- Napping before a night shift can reduce mid-shift sleepiness

Environmental Optimization for Daytime Sleep¶

Daytime sleep requires more environmental support than nighttime sleep:

- Temperature: Keep the bedroom cool (65-68°F is still optimal)[^36]

- Darkness: Achieve as close to complete darkness as possible. This is critical

- Noise: Use earplugs, white noise machines, or both; consider soundproofing

- Household coordination: Enlist family members to minimize disruptions

Strategic Caffeine Use¶

Caffeine can improve night-shift alertness when used strategically:[^37]

- Consume caffeine in the first half of the shift, not the second half

- Allow at least 6 hours between caffeine consumption and planned sleep

- Be aware that caffeine doesn't eliminate sleep debt. It masks sleepiness

When to Refer for Shift Work Sleep Disorder¶

Refer clients to a sleep specialist if they experience:

- Persistent excessive sleepiness or insomnia lasting more than 3 months despite implementing strategies

- Safety concerns (drowsy driving, near-miss accidents)

- Significant mood changes or depression

- Symptoms persisting after a schedule change

Coaching in Practice: Working with Shift Workers¶

Client (Maria, nurse): "I'm exhausted all the time. I work three 12-hour day shifts, then three night shifts, then four days off. I can never get into a rhythm."

Coach: "That's one of the hardest schedules for sleep. Your body never fully adapts to either pattern. We're not going to fix this completely—let's aim for 'good enough' and minimize the worst impacts."

Maria: "What does that look like?"

Coach: "A few things. On your night-shift stretches, keep your sleep times consistent—sleep 8 AM to 4 PM every day, even on your days off if you can. Use bright light during the first half of your night shift to help you stay alert. And here's a key one: wear blue-blocking glasses on your drive home. That morning sun will wake your brain up when you need to sleep."

Maria: "What about the room? It's so hard to sleep during the day."

Coach: "Create a sleep cave. Blackout curtains are essential—complete darkness. White noise to block daytime sounds. Keep it cool. And limit your caffeine to the first 6 hours of your shift so it doesn't interfere with your sleep window."

Maria: "Will this actually help?"

Coach: "Honestly? It won't make your schedule easy. But most shift workers see real improvement with these changes. We're working with your biology, not against it."

[CHONK 4: Sleep Hygiene Protocols]¶

Duration: 7-9 Hours Consistently¶

The mortality data points to 7-8 hours as optimal, but individual needs vary slightly. Some people genuinely function well on 7 hours; others need closer to 9.

Signs you may need more sleep:[^38]

- Needing an alarm to wake up

- Feeling drowsy during low-stimulation activities (meetings, reading)

- Caffeine dependence to feel alert

- "Catching up" on weekends (sleeping 2+ hours longer than weekdays)

Protocol guidance: Aim for 7-9 hours of sleep opportunity (time in bed). If you're consistently awake for extended periods in bed, you may need less time in bed. Sleep restriction is actually a component of treating insomnia.

Timing Consistency: The ±30 Minute Rule¶

Here's the finding that surprises many people: sleep regularity may be more important than sleep duration for longevity.

In a UK Biobank analysis of nearly 61,000 participants with actigraphy data, higher sleep regularity was associated with 20-48% lower all-cause mortality. Adding sleep duration to the statistical model didn't improve prediction.[^39] Similar findings emerged in the MESA cohort.[^40]

What this means practically: Going to bed and waking up at approximately the same times every day—within about ±30 minutes—provides powerful health benefits. This applies to weekends too.

The most damaging pattern for circadian health is "social jet lag." Maintaining one schedule during the workweek and a dramatically different schedule on weekends is harmful. Each hour of shift is associated with measurable health impacts.

Environment: Temperature, Darkness, and Quiet¶

Temperature: For most adults, the optimal bedroom temperature is 65-68°F (18-20°C). This facilitates the natural drop in core body temperature that signals sleep onset.[^41]

Important caveat: Older adults may sleep better at warmer temperatures (68-77°F). One study found that sleep efficiency in older adults peaked in this higher range.[^42] This is another area where individualization matters.

Bedding insulation shifts the effective comfort range. With a heavy duvet, comfortable sleep is possible even in rooms as cool as 46°F; with lighter bedding, the optimal range narrows.[^43]

Darkness: Sleep in as much darkness as possible. Even modest room light (100 lux, about what you'd get from a dim lamp or TV) during sleep increases heart rate, reduces deep and REM sleep, and impairs morning glucose regulation.[^44]

Practical steps:

- Use blackout curtains or an eye mask

- Cover electronic indicator lights

- Avoid checking phones during the night (the light exposure itself is disruptive)

Quiet: Noise disrupts sleep in dose-response fashion. Each 10 dB increase in nighttime outdoor noise approximately doubles the odds of high sleep disturbance.[^45] Indoor noise also matters. Each 1 dB increase in indoor nighttime noise reduces sleep efficiency by approximately 0.2%.[^46]

Strategies:

- Use earplugs (foam earplugs can reduce noise by 20-30 dB)

- Use white noise or a fan to mask variable noises

- Address the noise source when possible (close windows, fix squeaky fans)

Pre-Sleep Routine: Wind-Down and Screen Avoidance¶

The brain doesn't have an on/off switch. Transitioning from high-stimulation activities to sleep requires a buffer period.

1-2 hours before bed:

- Dim lights throughout the home

- Avoid screens, or use night-mode settings combined with reduced brightness

- Engage in low-stimulation activities: reading, gentle stretching, conversation, journaling

Avoid:

- Work emails or stressful conversations

- Intense exercise (moderate exercise earlier in the day improves sleep)

- Bright overhead lighting

Food Timing: Last Meal 2-3 Hours Before Bed¶

Eating close to bedtime can impair sleep quality through multiple mechanisms: digestive activity, blood sugar fluctuations, and circadian desynchronization.[^47]

Protocol guidance: Finish your last substantial meal 2-3 hours before your target bedtime. A small snack is generally fine, but avoid large meals within that window.

Supplement Support: General Practitioner-Supported Guidelines¶

Several supplements have practitioner support for sleep, though individual responses vary significantly. These are general guidelines. Individual needs differ, and clients should consult healthcare providers for personalized recommendations.

Magnesium (Bisglycinate or L-Threonate): General guidelines suggest 200-600mg. Magnesium plays a role in GABA receptor function and may support relaxation. The bisglycinate and L-threonate forms are often preferred for sleep support due to better absorption and less GI effects.[^48]

Glycine: General guidelines suggest 2-3g before bed. Glycine may help lower core body temperature and improve sleep quality.[^49]

L-Theanine: General guidelines suggest 100-200mg. L-theanine promotes alpha brain waves associated with calm alertness and may help with sleep onset without causing grogginess.[^50]

Apigenin: General guidelines suggest 50mg. A flavonoid found in chamomile, apigenin acts as a mild anxiolytic and may support sleep onset.[^51]

Important: Supplements are not substitutes for good sleep hygiene. They work best as part of a comprehensive approach.

[CHONK 5: Coaching Sleep — Practical Application]¶

Assessment: Current Sleep Quality and Habits¶

Before making recommendations, understand your client's current situation. Key questions:

Quantity:

- What time do you typically go to bed and wake up?

- How many hours of sleep do you get on weeknights? Weekends?

- How consistent are your sleep and wake times?

Quality:

- How long does it typically take you to fall asleep?

- Do you wake during the night? How often? For how long?

- How refreshed do you feel upon waking?

- Do you nap? When and for how long?

Environment and habits:

- What does your bedroom environment look like? (Temperature, light, noise)

- What do you do in the hour before bed?

- What's your caffeine intake and timing?

- Do you use any sleep aids (supplements, medications)?

Red flags (discussed in referral section):

- Loud snoring with witnessed pauses in breathing

- Excessive daytime sleepiness despite adequate sleep time

- Acting out dreams or unusual movements during sleep

- Restless legs or periodic limb movements

Common Barriers and Solutions¶

"I can't shut my mind off."

Racing thoughts at bedtime often reflect inadequate wind-down time or unprocessed stress. Solutions:

- Earlier wind-down routine (90+ minutes before bed)

- "Worry journal", writing down concerns before bed to externalize them

- Relaxation techniques: deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, body scans

- If persistent and impairing, refer for CBT-I (cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia)

"I wake up at 3 AM and can't fall back asleep."

Middle-of-the-night awakenings have many causes. Assessment matters:

- If awakened by noise or bladder: address those specific causes

- If mind starts racing upon waking: same strategies as "can't shut my mind off"

- If occurring regularly without obvious cause: screen for depression and anxiety

- If accompanied by snoring/gasping: screen for sleep apnea

"I don't have time to sleep 7-8 hours."

This requires exploring priorities and trade-offs. Often, time "saved" by sleeping less is lost to reduced productivity, longer task completion, and health consequences. Help clients examine:

- What activities could shift to accommodate more sleep?

- What would they be willing to experiment with for 2 weeks?

- What's the actual cost of their current sleep pattern?

"I'm a night owl. I can't fall asleep early."

True chronotype differences exist, but many "night owls" have simply drifted into late schedules through habits. Gradual schedule shifts (15-30 minutes earlier per week), combined with morning light and evening light reduction, can advance sleep timing for most people.

Avoiding Orthosomnia: The Sleep Score Trap¶

This may be the most important coaching skill in sleep optimization: helping clients avoid making their sleep worse by trying to make it better.

Orthosomnia is a term coined by researchers to describe the anxiety and sleep disturbance caused by obsessive monitoring of sleep tracking data.[^52] The pattern is familiar:

- Client gets a sleep tracker

- Client sees a "poor sleep score" one night

- Client worries about their sleep

- Worry makes sleep worse

- Sleep score gets worse

- More worry → worse sleep → worse scores...

Signs of orthosomnia:

- Excessive focus on nightly sleep scores

- Anxiety when scores are "bad"

- Changing behavior based on scores rather than how they feel

- Spending significant time trying to "optimize" sleep metrics

Coaching approach:

Use wearables for trends, not single nights. Sleep tracking is useful for identifying patterns over weeks, not for evaluating any individual night. Encourage clients to look at 7-day or 30-day averages, not daily scores.

Subjective experience matters more than scores. Ask: "How did you feel when you woke up?" rather than "What was your sleep score?" If someone feels rested, they probably slept well enough, regardless of what their watch says.

Sleep tracking can't measure sleep quality accurately. Consumer wearables estimate sleep stages using movement and heart rate. They're approximations, not measurements. Sleep scores are calculated using proprietary algorithms that may not reflect individual needs.

"Good enough" is the goal. Perfect sleep doesn't exist. Some nights will be worse than others. The goal is sustainable habits that support generally adequate sleep, not optimizing every variable to perfection.

Coaching in Practice: Managing the Perfectionist Sleeper¶

Client (James, 38): "I've done everything. Blackout curtains, 65 degrees, no screens, supplements—everything. My sleep score is still stuck at 72. I need to get it above 80."

Coach: "You've clearly put a lot of work into this. Can I ask you something? What would change in your life if your score went from 72 to 80?"

James: "I'd... sleep better?"

Coach: "Would you feel different? Function better during the day?"

James: "I mean, probably? I don't know."

Coach: "Here's what I'm noticing: you've developed really good sleep habits, but you've also developed anxiety about sleep itself. That anxiety might be hurting your sleep more than the things you're trying to optimize."

James: "So what do I do?"

Coach: "There's actually research on this—they call it orthosomnia. Monitoring sleep too closely can make it worse for some people. Here's an experiment: put the tracker away for two weeks. Just notice how you feel when you wake up. I'm curious whether your experience of sleep changes when you're not measuring it."

James: "But how will I know if I'm sleeping well?"

Coach: "That's the point. You'll know because of how you feel, not because of a number on a screen. 'Good enough' is the goal here, not perfect."

Sleep Disorder Red Flags: When to Refer Out¶

Coaches can support sleep hygiene, but sleep disorders require medical evaluation. Know these red flags:

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) indicators:

- Loud, habitual snoring

- Witnessed pauses in breathing during sleep (apneas)

- Gasping or choking awakening

- Excessive daytime sleepiness despite adequate sleep time

- Morning headaches

- High-risk groups: BMI >30, large neck circumference (>17" men, >16" women), male sex

OSA is far more common than many realize. In athletes, prevalence ranges from 7% to 86% depending on sport, with contact sports like rugby and American football showing the highest rates.[^53] A study of collegiate football players found 35% had mild-to-moderate OSA.[^54]

Validated screening: The STOP-Bang questionnaire is a simple, validated tool:[^55]

- Snoring loudly

- Tired during the day

- Observed apneas

- Pressure (high blood pressure)

- BMI >35

- Age >50

- Neck circumference large

- Gender male

A score of ≥3 suggests moderate-to-high risk and warrants referral for sleep testing.

Insomnia disorder indicators:

- Difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep ≥3 nights/week for ≥3 months

- Significant daytime impairment

- Symptoms persist despite good sleep opportunity

Chronic insomnia responds well to cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), which is more effective than medication for long-term outcomes.[^56] Refer to a behavioral sleep medicine provider or sleep clinic.

Other urgent referrals:

- Restless legs syndrome: Uncomfortable sensations in legs with urge to move, worse at rest and evening

- REM sleep behavior disorder: Acting out dreams, potentially violently (associated with future neurodegenerative disease)

- Narcolepsy indicators: Sudden sleep attacks, cataplexy (emotion-triggered muscle weakness)

- Drowsy driving or near-miss accidents: Immediate safety concern

The scope reminder: Coaches do not diagnose sleep disorders. We screen, refer, and support. Diagnosis and treatment are medical acts. This aligns with Chapter 1.5's scope of practice guidance.

The "Good Enough" Mindset for Sleep¶

Sleep optimization can become its own form of stress. The healthiest approach is one that:

- Prioritizes consistency over perfection

- Focuses on sustainable habits, not maximum optimization

- Recognizes that some nights will be worse than others

- Treats sleep as one component of overall health, not a separate project to master

The irony: Over-optimizing sleep can cause insomnia. Present sleep hygiene recommendations as "things that help most people" rather than "rules you must follow."

Hierarchy of sleep priorities:

1. Consistency first: same bed and wake times (±30 minutes)

2. Duration second: aim for 7-9 hours of opportunity

3. Environment third: dark, quiet, cool

4. Advanced interventions last. Supplements, tracking, optimization

Most clients will see significant improvement from the first three. Only pursue optimization beyond that if the fundamentals are solid and additional gains are desired.

[CHONK 6: Deep Health Integration]¶

Deep Health Integration¶

Sleep affects every dimension of Deep Health. As you work with clients on sleep optimization, consider how sleep connects to the full picture of their wellbeing.

Physical health¶

The most obvious connection: sleep is when your body repairs, rebuilds, and restores.

- Muscle protein synthesis and tissue repair occur during deep sleep

- Immune function restoration depends on adequate sleep

- Hormone regulation (growth hormone release, cortisol cycling) is sleep-dependent

- Metabolic health markers decline with chronic sleep restriction

Emotional health¶

Sleep and emotional regulation are bidirectionally connected:

- REM sleep processes emotional memories and experiences

- Sleep deprivation impairs emotional control and increases reactivity

- Better sleep contributes to more stable mood throughout the day

- Chronic insomnia is strongly associated with anxiety and depression

Mental/cognitive health¶

Your brain needs sleep to function at its best:

- Memory consolidation occurs during both deep sleep and REM sleep

- Creativity and problem-solving improve with adequate rest

- Glymphatic clearance removes metabolic waste that impairs cognition

- Attention, decision-making, and executive function all decline with poor sleep

Social/relational health¶

Sleep affects how we connect with others:

- Shared sleep environments create both challenges and intimacy (partners, families)

- Sleep deprivation reduces empathy and social engagement

- "Social jet lag" from inconsistent schedules can strain relationships

- Prioritizing sleep sometimes means negotiating with family about schedules

Environmental health¶

Your sleep environment matters:

- Darkness, temperature, and noise levels directly affect sleep quality

- Air quality in the bedroom affects respiratory function during sleep

- Technology and light exposure are environmental factors to manage

- Creating a sleep sanctuary may require home modifications

Existential/purposeful health¶

Sleep enables purpose:

- Energy for meaningful activities comes from restorative sleep

- Cognitive clarity for pursuing goals depends on adequate rest

- Preventing burnout that derails purpose requires recovery

- Sleep can be reframed not as "lost time" but as investment in what matters

Study Guide Questions¶

-

What is the glymphatic system, and why is deep sleep important for its function?

-

Explain the U-shaped relationship between sleep duration and mortality. What is the optimal sleep duration range according to current evidence?

-

Why might sleep regularity be more important than sleep duration for long-term health outcomes?

-

Describe the circadian rhythm and identify three practical ways to strengthen circadian alignment.

-

What are the key environmental factors that support optimal sleep, and what are the recommended parameters for each?

-

How would you explain orthosomnia to a client, and what strategies would you use to help them avoid it?

-

What are the major red flags that would prompt you to refer a client for sleep disorder evaluation?

-

Describe three evidence-based strategies for helping shift workers optimize their sleep.

-

What is the recommended protocol for food timing relative to bedtime, and what is the rationale?

-

How does the "good enough" mindset apply to sleep coaching, and why is it important?

Self-reflection questions:

-

Track your sleep for one week: What time do you go to bed? Wake up? How consistent is this across the week? What pattern emerges?

-

Look at your sleep environment: Is it dark enough? Cool enough? Quiet enough? What's one change you could make tonight?

Deep Dives¶

Want to go deeper? These supplemental articles explore key topics from this chapter in more detail.

- Sleep Disorders Primer. What coaches should know (scope-appropriate)

- Chronotype Considerations. Morningness/eveningness in coaching

References¶

-

Ibrahim A, Högl B, Stefani A. Sleep as the Foundation of Brain Health. Seminars in Neurology. 2025;45(03):305-316. doi:10.1055/a-2566-4073

-

Chong PL, Garic D, Shen MD, Lundgaard I, Schwichtenberg AJ. Sleep, cerebrospinal fluid, and the glymphatic system: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2022;61:101572. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101572

-

Zhou W, Karan KR, Gu W, Klein H, Sturm G, De Jager PL, et al. Somatic nuclear mitochondrial DNA insertions are prevalent in the human brain and accumulate over time in fibroblasts. PLOS Biology. 2024;22(8):e3002723. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3002723

-

Hauglund NL, Andersen M, Tokarska K, Radovanovic T, Kjaerby C, Sørensen FL, et al. Norepinephrine-mediated slow vasomotion drives glymphatic clearance during sleep. Cell. 2025;188(3):606-622.e17. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2024.11.027

-

Bao W, Feng C, Wang C, Liu D, Fan X, Liang P. Polyoxometalates in Electrochemical Energy Storage: Recent Advances and Perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025;26(21):10267. doi:10.3390/ijms262110267

-

ScienceDaily. Some sleep medications reduce brain's ability to wash away waste during sleep. 2025. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/01/250108143735.htm

-

Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams. Available from: https://www.amazon.com/Why-We-Sleep-Unlocking-Dreams/dp/1501144316

-

Stickgold R, Walker MP. Sleep-dependent memory triage: evolving generalization through selective processing. Nature Neuroscience. 2013;16(2):139-145. doi:10.1038/nn.3303

-

Ungvari Z, Fekete M, Varga P, Fekete JT, Lehoczki A, Buda A, et al. Imbalanced sleep increases mortality risk by 14–34%: a meta-analysis. GeroScience. 2025;47(3):4545-4566. doi:10.1007/s11357-025-01592-y

-

Jin Q, Yang N, Dai J, Zhao Y, Zhang X, Yin J, et al. Association of Sleep Duration With All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality: A Prospective Cohort Study. Frontiers in Public Health. 2022;10. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.880276

-

Normal Human Sleep: An Overview. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2004.01.001

-

Voumvourakis KI, Sideri E, Papadimitropoulos GN, Tsantzali I, Hewlett P, Kitsos D, et al. The Dynamic Relationship between the Glymphatic System, Aging, Memory, and Sleep. Biomedicines. 2023;11(8):2092. doi:10.3390/biomedicines11082092

-

Massey A, Boag M, Magnier A, Bispo D, Khoo T, Pountney D. Glymphatic System Dysfunction and Sleep Disturbance May Contribute to the Pathogenesis and Progression of Parkinson’s Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23(21):12928. doi:10.3390/ijms232112928

-

Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, Vitiello MV. Meta-Analysis of Quantitative Sleep Parameters From Childhood to Old Age in Healthy Individuals: Developing Normative Sleep Values Across the Human Lifespan. Sleep. 2004;27(7):1255-1273. doi:10.1093/sleep/27.7.1255

-

Diekelmann S, Born J. The memory function of sleep. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2010;11(2):114-126. doi:10.1038/nrn2762

-

New wearable device monitors brain waste clearance during sleep. Available from: https://www.msn.com/en-gb/health/familyhealth/new-wearable-device-monitors-brain-waste-clearance-during-sleep/ar-AA1FP24V?apiversion=v2&domshim=1&noservercache=1&noservertelemetry=1&batchservertelemetry=1&renderwebcomponents=1&wcseo=1

-

Li J, Vitiello MV, Gooneratne NS. Sleep in Normal Aging. Sleep Medicine Clinics. 2018;13(1):1-11. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2017.09.001

-

Reppert SM, Weaver DR. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature. 2002;418(6901):935-941. doi:10.1038/nature00965

-

de Menezes-Júnior LAA, Sabião TdS, Carraro JCC, Machado-Coelho GLL, Meireles AL. The role of sunlight in sleep regulation: analysis of morning, evening and late exposure. BMC Public Health. 2025;25(1). doi:10.1186/s12889-025-24618-8

-

Kwon S, Lee S, Kang M, Huh D, Lee Y. The Epidemiologic Characteristics of Malignant Mesothelioma Cases in Korea: Findings of the Asbestos Injury Relief System from 2011–2015. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(19):10007. doi:10.3390/ijerph181910007

-

Wright KP, McHill AW, Birks BR, Griffin BR, Rusterholz T, Chinoy ED. Entrainment of the Human Circadian Clock to the Natural Light-Dark Cycle. Current Biology. 2013;23(16):1554-1558. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.06.039

-

Brown TM, Brainard GC, Cajochen C, Czeisler CA, Hanifin JP, Lockley SW, et al. Recommendations for daytime, evening, and nighttime indoor light exposure to best support physiology, sleep, and wakefulness in healthy adults. PLOS Biology. 2022;20(3):e3001571. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3001571

-

Fernandez F. Current Insights into Optimal Lighting for Promoting Sleep and Circadian Health: Brighter Days and the Importance of Sunlight in the Built Environment. Nature and Science of Sleep. 2022;Volume 14:25-39. doi:10.2147/nss.s251712

-

Mason IC, Grimaldi D, Reid KJ, Warlick CD, Malkani RG, Abbott SM, et al. Light exposure during sleep impairs cardiometabolic function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2022;119(12). doi:10.1073/pnas.2113290119

-

Panda S. Circadian physiology of metabolism. Science. 2016;354(6315):1008-1015. doi:10.1126/science.aah4967

-

Harding EC, Franks NP, Wisden W. The Temperature Dependence of Sleep. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2019;13. doi:10.3389/fnins.2019.00336

-

Shift Work, Shift-Work Disorder, and Jet Lag. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4160-6645-3.00071-2

-

Boivin DB, Boudreau P, Kosmadopoulos A. Disturbance of the Circadian System in Shift Work and Its Health Impact. Journal of Biological Rhythms. 2021;37(1):3-28. doi:10.1177/07487304211064218

-

Xi J, Ma W, Tao Y, Zhang X, Liu L, Wang H. Association between night shift work and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Frontiers in Public Health. 2025;13. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2025.1668848

-

Reinganum MI, Thomas J. Shift Work Hazards. StatPearls; 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK589670/

-

González-Cano-Caballero M, Torrejón-Guirado M, Cano-Caballero MD, Mac Fadden I, Barrera-Villalba M, Lima-Serrano M. Adolescents and youths’ opinions about the factors associated with cannabis use: a qualitative study based on the I-Change model. BMC Nursing. 2023;22(1). doi:10.1186/s12912-023-01283-z

-

Zhao C, Li N, Miao W, He Y, Lin Y. A systematic review and meta-analysis on light therapy for sleep disorders in shift workers. Scientific Reports. 2025;15(1). doi:10.1038/s41598-024-83789-3

-

LOWDEN A, ÖZTÜRK G, REYNOLDS A, BJORVATN B. Working Time Society consensus statements: Evidence based interventions using light to improve circadian adaptation to working hours. Industrial Health. 2019;57(2):213-227. doi:10.2486/indhealth.sw-9

-

Harrison EM, Easterling AP, Yablonsky AM, Glickman GL. Sleep-Scheduling Strategies in Hospital Shiftworkers. Nature and Science of Sleep. 2021;Volume 13:1593-1609. doi:10.2147/nss.s321960

-

Zhao N, Zhao Y, An F, Zhang Q, Sha S, Su Z, et al. Network analysis of comorbid insomnia and depressive symptoms among psychiatric practitioners during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2023;19(7):1271-1279. doi:10.5664/jcsm.10586

-

Sleep Foundation. The Best Temperature for Sleep. 2024. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/bedroom-environment/best-temperature-for-sleep

-

Wu Y, Huang X, Zhong C, Wu T, Sun D, Wang R, et al. Efficacy of Dietary Supplements on Sleep Quality and Daytime Function of Shift Workers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2022;9. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.850417

-

American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Adult Sleep Duration Health Advisory. 2015. https://aasm.org/advocacy/position-statements/adult-sleep-duration-health-advisory/

-

Windred DP, Burns AC, Lane JM, Saxena R, Rutter MK, Cain SW, et al. Sleep regularity is a stronger predictor of mortality risk than sleep duration: A prospective cohort study. SLEEP. 2023;47(1). doi:10.1093/sleep/zsad253

-

Howley MM, Werler MM, Fisher SC, Tracy M, Van Zutphen AR, Papadopoulos EA, et al. Maternal exposure to zolpidem and risk of specific birth defects. Journal of Sleep Research. 2023;33(1). doi:10.1111/jsr.13958

-

Baniassadi A, Manor B, Yu W, Travison T, Lipsitz L. Nighttime ambient temperature and sleep in community-dwelling older adults. Science of The Total Environment. 2023;899:165623. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165623

-

Nighttime Ambient Temperature and Sleep in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165623

-

Sleep Foundation. How Bedroom Temperatures and Bedding Choices Impact Your Sleep. 2023. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/sleep-news/bedroom-temperatures-and-bedding-choices-affect-sleep

-

Light exposure during sleep impairs cardiometabolic function. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2113290119

-

Smith MG, Cordoza M, Basner M. Environmental Noise and Effects on Sleep: An Update to the WHO Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2022;130(7). doi:10.1289/ehp10197

-

Kwon H, Walsh KG, Berja ED, Manoach DS, Eden UT, Kramer MA, et al. Sleep spindles in the healthy brain from birth through 18 years. Sleep. 2023;46(4). doi:10.1093/sleep/zsad017

-

Crispim CA, Zimberg IZ, dos Reis BG, Diniz RM, Tufik S, de Mello MT. Relationship between Food Intake and Sleep Pattern in Healthy Individuals. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2011;07(06):659-664. doi:10.5664/jcsm.1476

-

The effect of magnesium supplementation on primary insomnia in elderly. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23853635/

-

YAMADERA W, INAGAWA K, CHIBA S, BANNAI M, TAKAHASHI M, NAKAYAMA K. Glycine ingestion improves subjective sleep quality in human volunteers, correlating with polysomnographic changes. Sleep and Biological Rhythms. 2007;5(2):126-131. doi:10.1111/j.1479-8425.2007.00262.x

-

Rao TP, Ozeki M, Juneja LR. In Search of a Safe Natural Sleep Aid. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2015;34(5):436-447. doi:10.1080/07315724.2014.926153

-

Salehi B, Venditti A, Sharifi-Rad M, Kręgiel D, Sharifi-Rad J, Durazzo A, et al. The Therapeutic Potential of Apigenin. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019;20(6):1305. doi:10.3390/ijms20061305

-

Baron KG, Abbott S, Jao N, Manalo N, Mullen R. Orthosomnia: Are Some Patients Taking the Quantified Self Too Far?. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2017;13(02):351-354. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6472

-

Sleep Medicine. A systematic review on sleep-related breathing disorders in athletes and para-athletes. Sleep Medicine; 2025. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S138994572500557X

-

Parthasarathy S. Patient-centered care in the era of technological revolutions and permacrisis Commentary on Jones TA, Roddis J, Stores R. Patient experience of the use of continuous positive airway pressure for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea with or without telemedicine during COVID-19: a qualitative approach.

J Clin Sleep Med

. 2024;20(11):1739–1748. doi:10.5664/jcsm.11266. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2024;20(11):1719-1721. doi:10.5664/jcsm.11354 -

Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, Chung SA, Vairavanathan S, Islam S, et al. STOP Questionnaire. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(5):812-821. doi:10.1097/aln.0b013e31816d83e4

-

Edinger JD, Arnedt JT, Bertisch SM, Carney CE, Harrington JJ, Lichstein KL, et al. Behavioral and psychological treatments for chronic insomnia disorder in adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2021;17(2):255-262. doi:10.5664/jcsm.8986