Unit 2: Core Interventions—The Protocol¶

Chapter 2.10: Movement Quality and Stability¶

[CHONK: 1-minute summary]

The big idea¶

Chapter 2.9 established that exercise is the most powerful longevity intervention available. Combining cardio and strength training cuts mortality risk by roughly 40 percent. But here's what the research also shows: how you move matters as much as whether you move. The quality of your movement, your mobility, balance, and functional capacity, independently predicts how long you'll live and how well you'll age.

Consider this statistic: adults who score poorly on the sitting-rising test (a simple measure of getting up and down from the floor without support) have a 5-6 times higher risk of death compared to those who score perfectly.[^1] Nearly half of community-dwelling older adults cannot rise from the floor unassisted.[^2] Falls are the leading cause of injury-related death in adults over 65. These aren't problems that more treadmill time solves.

This chapter is the quality complement to Chapter 2.9's quantity focus. You'll learn functional assessments that predict longevity, daily mobility protocols that maintain joint health, and balance training progressions that prevent falls. By the end, you'll understand not just what to do, but why movement quality is the currency of independence as we age.

Key takeaways:

- Sit-to-rise test: Each point lost = ~21% higher mortality; scores 0-4 = 5.44x death risk vs perfect score

- Balance ability: Each additional second = ~10% lower mortality

- Mobility protocol: 10-15 minutes daily focusing on hip flexors, thoracic spine, and ankles

- Balance training: 2x/week significantly reduces fall risk (23-34% reduction)

- Grip strength: Track weekly; target 70+ lbs (a proxy for overall functional capacity)

- These assessments and interventions are within coaching scope. You educate and support

[CHONK: Section 1 - Functional Movement: The Quality of Quantity]

Functional movement: The quality of quantity¶

The 80-year-old-you question¶

In Chapter 2.9, we asked clients to imagine their 80-year-old self and what they want to be able to do. Play with grandchildren, travel independently, maintain hobbies. Now let's get specific: Can that future self get down to the floor to play with a toddler? Can they get back up without grabbing furniture?

This isn't a hypothetical concern. Nearly half of community-dwelling older adults cannot rise from the floor unassisted.[^2] For those who can't, the consequences ripple outward: higher fall risk, increased hospitalization, greater caregiver burden, and, starkly, higher mortality.[^3]

Functional movement is the bridge between exercise capacity and real-world independence. A client might have a reasonable VO2 max and decent leg strength, but if their hip mobility prevents them from getting into a deep squat, or their balance fails when transitioning positions, that fitness doesn't fully translate to function.

Quality vs. quantity: The missing dimension¶

Chapter 2.9 covered the "quantity" side of exercise—how much cardio, how many strength sessions, and what intensity targets. This chapter addresses the quality dimension:

- Mobility: Can joints move through full, functional ranges of motion?

- Balance: Can you maintain stability during movement and position changes?

- Functional capacity: Can you perform real-world tasks that require integrated movement: sitting, rising, bending, reaching?

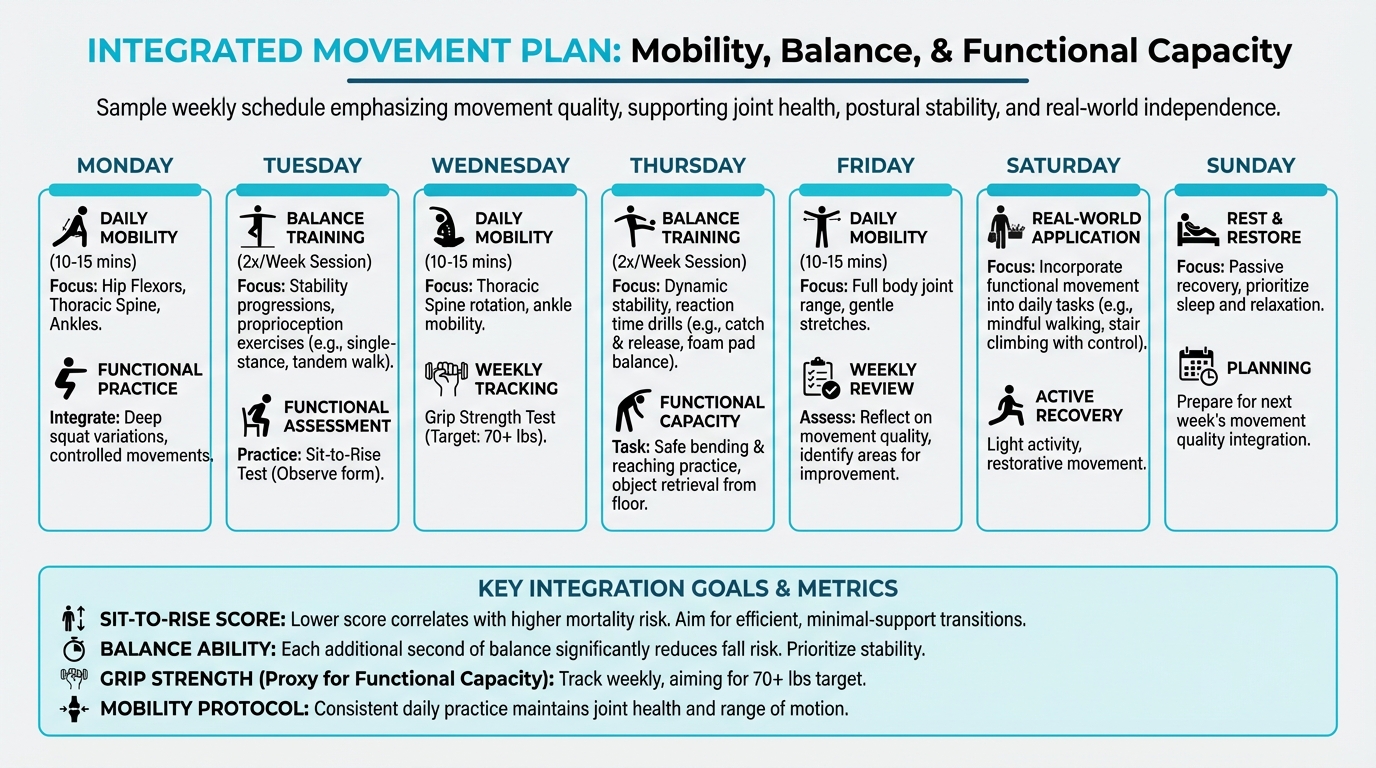

Figure: Integrated movement plan

These aren't just nice-to-haves. Each dimension independently predicts mortality and disability, often as strongly as measures like grip strength or cardiorespiratory fitness.

Use it or lose it: The biology of functional decline¶

The human body adapts to the demands placed on it, and also to the demands not placed on it. This principle, which drives strength gains with progressive overload, also drives functional decline with disuse.

What happens with aging and inactivity:

- Joint range of motion decreases: Hip extension (critical for walking) declines by approximately 20% between ages 25 and 74.[^4]

- Balance systems deteriorate: Vestibular (inner ear), proprioceptive (joint position sense), and visual inputs all degrade, compounding fall risk.[^5]

- Movement patterns simplify: Without practice, the body "forgets" complex movements like getting up from the floor or rotating the spine.

- Reaction time slows: The speed of postural corrections, catching yourself before a fall, decreases with age.

The good news: all of these are modifiable. Regular mobility work maintains joint range, balance training improves postural stability, and functional movement practice keeps neural pathways sharp; the research is clear that targeted training improves these capacities even into the ninth decade of life.[^6]

Functional independence as the goal¶

What we're really training for isn't abstract fitness. It's functional independence: the ability to live without assistance, to manage activities of daily living (ADLs), to maintain autonomy.

Research shows that functional limitations and ADL disabilities are strongly linked to shorter survival. In a Chinese cohort of over 12,000 older adults, those with functional limitations survived an average of 55-61 months, significantly less than their peers without limitations.[^7] Among the "oldest old" (80+), ADL status and lifestyle were the two most important modifiable factors affecting survival.[^8]

This reframes why we care about sitting and rising, about balance, about mobility: these aren't exercises for their own sake. They're the physical building blocks of independence. When clients understand this connection—between today's movement practice and tomorrow's autonomy—motivation shifts from "should" to "want."

Coaching in Practice: "This Doesn't Feel Like Real Exercise"¶

Client: "Stretching and balance work? I thought we were going to do real exercise."

Coach: "I get it. But the purpose of exercise isn't to get better at exercise. It's to get better at life. Strength training builds muscle. Mobility work ensures you can use that muscle through full ranges. Balance training means that muscle keeps you upright when you need it most."

Client: "I guess, but I feel like I should be sweating."

Coach: "Think about what you actually want. You want to pick things up off the floor without pain. Catch yourself if you trip. Travel comfortably for decades. That's what functional movement is—making sure your fitness translates to your actual life, not just to gym performance."

[CHONK: Section 2 - Assessment: Testing Functional Capacity]

Assessment: Testing functional capacity¶

Why test functional capacity?¶

Chapter 1.4 introduced you to longevity biomarkers: objective measures that predict health outcomes. Functional assessments are among the most powerful predictors we have, and they require no expensive equipment or laboratory analysis.

These tests serve multiple purposes:

1. Baseline assessment: Where does the client stand?

2. Mortality risk stratification: Who needs the most attention?

3. Progress tracking: Are interventions working?

4. Client motivation: Concrete numbers drive engagement

The tests below are validated, simple to conduct, and meaningful. As a coach, you can educate clients about these assessments, help them understand their scores, and support improvement, while referring to physical therapists or physicians for clients who show significant limitations or safety concerns.

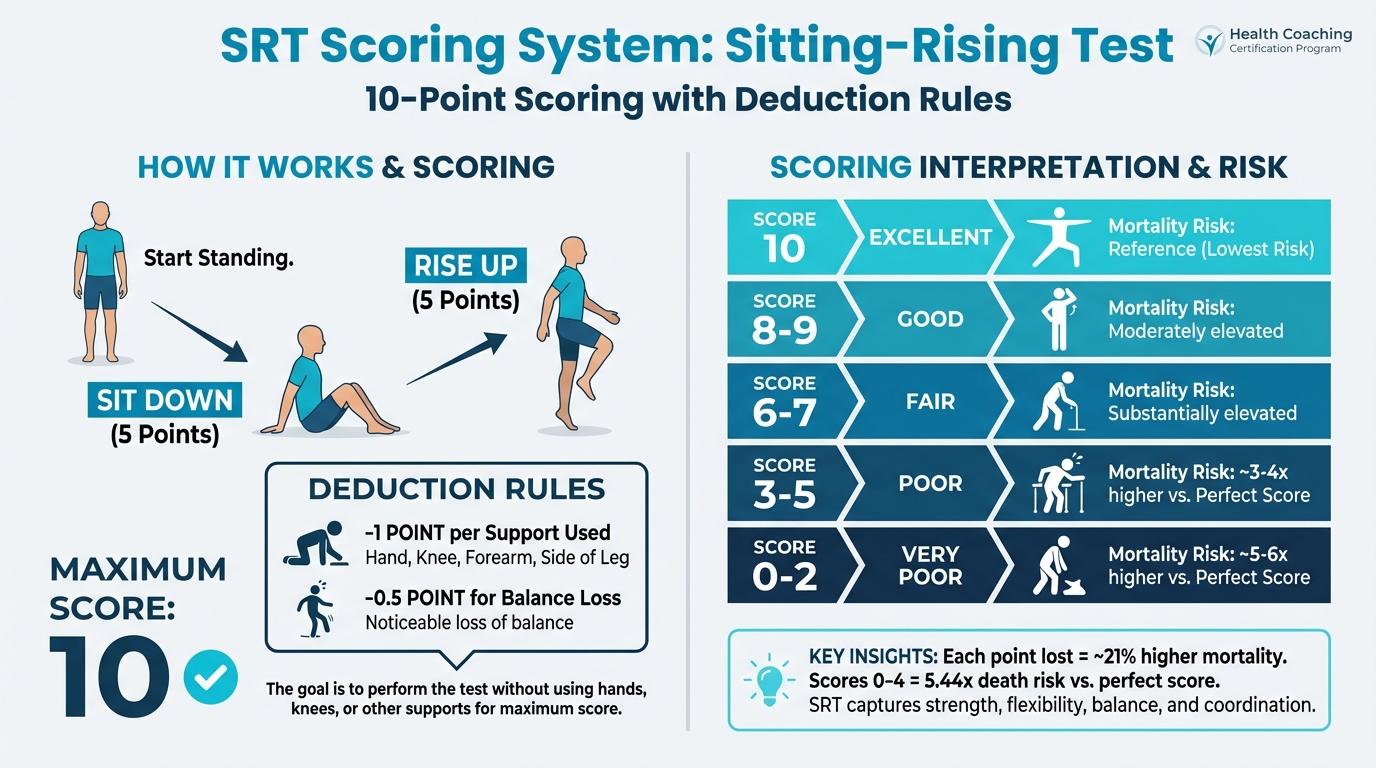

The sitting-rising test (SRT)¶

The sitting-rising test is perhaps the most powerful simple assessment of musculoskeletal fitness we have. It measures the ability to sit down on the floor and rise back up without using supports.

How it works:

- Start standing

- Sit down on the floor (without using hands, knees, or other supports)

- Rise back to standing (again without supports)

- Maximum score: 10 points (5 for sitting, 5 for rising)

- Deduct 1 point for each support used (hand, knee, forearm, side of leg)

- Deduct 0.5 points for noticeable loss of balance

What the research shows:

In 4,282 adults followed for a median of 12.3 years, mortality was 3.7% for those who scored 10 (perfect) versus 42.1% for those who scored 0-4.[^1] That's not a typo. Those with the lowest scores had more than ten times the death rate.

Table 10.1: Sitting-Rising Test Interpretation

| SRT Score | Risk Category | Mortality Risk vs. Perfect Score |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | Excellent | Reference |

| 8-9 | Good | Moderately elevated |

| 6-7 | Fair | Substantially elevated |

| 3-5 | Poor | ~3-4x higher |

| 0-2 | Very Poor | ~5-6x higher |

Why it predicts mortality:

The SRT captures integrated "non-aerobic" fitness: strength (especially lower body), flexibility, balance, and motor coordination. It's not about one dimension. It's about how well all systems work together for a fundamental human task: getting up and down.

Figure: 10-point scoring with deduction rules

For older or less mobile clients:

- Allow practice attempts first

- Ensure a safe environment (clear space, non-slip surface)

- Have support available nearby if needed

- A score below 8 in adults 51-80 warrants attention

- Any client unable to perform the test should be referred for physical therapy evaluation

The floor-to-standing assessment¶

Related to the SRT, this simpler assessment evaluates whether a client can get from the floor to standing at all, and how.

How it works:

- Start lying on your back on the floor

- Get to standing position

- Observe the strategy used: rolling to side, pushing up to hands and knees, using furniture, etc.

Why it matters:

Falling and being unable to get up is a critical event. In older adults, time spent on the floor after a fall correlates with serious complications: hypothermia, dehydration, pressure injuries, and psychological trauma. Those who can't rise from the floor independently have higher hospitalization rates and mortality.[^2][^3]

What to look for:

- Can they do it at all?

- Do they need furniture or supports?

- How much effort does it require?

- What movement strategies do they use?

The Floor Transfer Test has been validated with high reliability (ICCs 0.73-1.00) and correlates strongly with overall function (Spearman ρ ≈ 0.86-0.93).[^9]

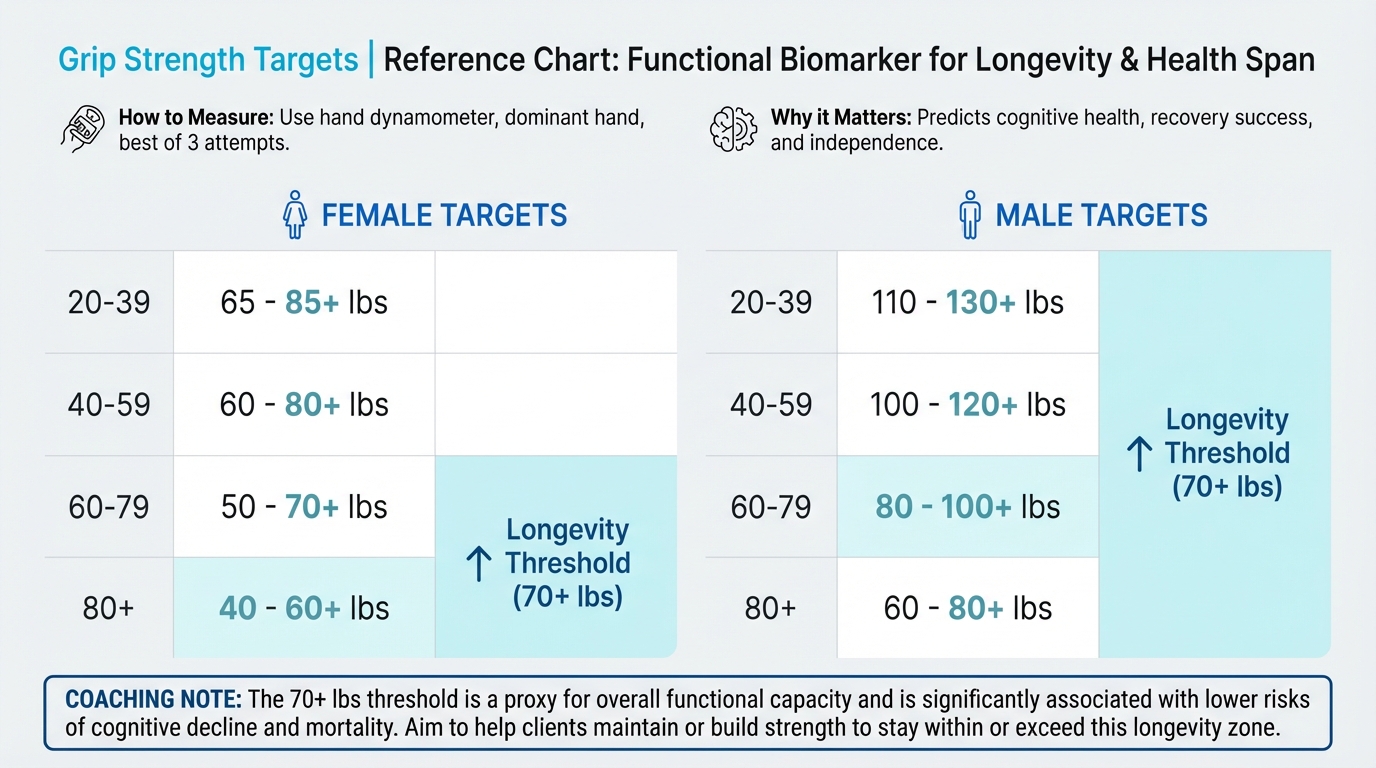

Grip strength: Your functional biomarker¶

We covered grip strength briefly in Chapter 2.9 as a longevity marker. Here's the deeper picture of what it predicts:

Figure: Targets by age/sex with longevity thresholds

Beyond mortality:

- Higher grip strength predicts lower risks of cognitive impairment (RR ≈ 0.58), all-cause dementia (RR ≈ 0.73), and Alzheimer's disease (RR ≈ 0.68)[^10]

- Each 1 kg increase in pre-rehabilitation grip strength increases odds of successful hip fracture rehabilitation by 6.8%[^11]

- Low grip strength increases odds of outpatient visits (OR ≈ 1.13), inpatient admissions (OR ≈ 1.51), and unmet hospital needs (OR ≈ 1.44)[^12]

How to measure:

- Use a hand dynamometer

- Measure dominant hand (or both)

- Take 2-3 attempts, use best score

- Compare to age/sex norms

Target: 70+ lbs (32+ kg) for longevity protection (per the longevity protocol)

Tracking recommendation: Weekly measurement provides trend data without excessive burden.

Timed up-and-go (TUG)¶

The TUG test measures functional mobility. The time to rise from a chair, walk 3 meters, turn around, walk back, and sit down.

How it works:

- Client starts seated in a standard chair (seat height ~46 cm)

- On "Go," they stand, walk 3 meters at comfortable pace, turn, walk back, and sit

- Time from "Go" to seated

What the numbers mean:

- <10 seconds: Normal mobility

- 10-14 seconds: Mildly impaired

- ≥14 seconds: High fall risk

- ≥20 seconds: Requires further evaluation

Critical threshold: TUG ≥9 seconds is associated with 2.66 times higher mortality risk.[^13]

One-legged stance test¶

Balance can be assessed simply by timing single-leg stance.

How it works:

- Stand on one leg, hands on hips

- Time until loss of balance or 30 seconds maximum

- Test both legs

What the research shows:

- Failing the single-leg stance test (unable to hold 10 seconds) increases odds of future falls by 54% (OR = 1.54)[^14]

- Each additional second of balance time is associated with approximately 10% lower mortality[^15]

- Adults who can hold for 10+ seconds have 39% lower mortality than those who cannot[^15]

Critical threshold: 10 seconds is a meaningful cutoff for increased mortality and fall risk

For older or less mobile clients:

- Perform near a wall or sturdy support (but don't touch during test)

- Have a spotter nearby

- Start with eyes open; eyes-closed testing is more challenging

When to refer¶

These assessments are within coaching scope for education and motivation. However, refer clients to physical therapy or physician when:

- Unable to perform SRT at all (score 0-2)

- Significant pain during assessments

- TUG >20 seconds

- Unable to stand on one leg for even a few seconds

- History of recent falls or near-falls

- Any neurological symptoms (dizziness, numbness, sudden weakness)

- Suspected pathology beyond deconditioning

Coaching in Practice: Delivering Difficult Test Results¶

Client: (just scored 4 on the sitting-rising test, looks worried) "That's bad, isn't it?"

Coach: "This test gives us information—it's a starting point, not a verdict. Everything we measured today is trainable. People significantly improve their scores with consistent practice."

Client: "But you said low scores are linked to mortality..."

Coach: "Think of it like a check engine light. It's telling us where to focus attention. Now we know that balance work and mobility practice should be priorities for you. And the research shows these things respond really well to training, even into your 80s and 90s."

Client: "So what do we do?"

Coach: "Given your score, I want you to work with a physical therapist first—they can design a safe progression. This is important enough to get specialized help. Then my role is to support you in building daily habits around whatever they recommend."

[CHONK: Section 3 - Mobility Practice: Daily Maintenance]

Mobility practice: Daily maintenance¶

Why daily mobility matters¶

The longevity protocol specifies 10-15 minutes of daily mobility work. But why daily? Why not twice a week like balance training?

The answer lies in the difference between maintenance and remediation:

- Maintenance (daily): Preserves existing range of motion, prevents stiffening, requires low time investment

- Remediation (less frequent, higher volume): Recovers lost range of motion, requires sustained stretching

Think of it like dental hygiene. Brushing daily prevents problems; it's easier than fixing cavities. Mobility work operates similarly. Regular short sessions maintain what you have, while recovering lost mobility requires much more intensive intervention.

The evidence: While research on specific daily stretching protocols is limited, studies consistently show that flexibility training improves range of motion, and that gains depend on dose: frequency, duration, and consistency all matter.[^16] For maintenance, brief daily practice appears more effective than longer, less frequent sessions.

The joint-by-joint approach: A functional overview¶

Not all joints need the same attention. The body alternates between joints that primarily need mobility (ability to move through range) and joints that primarily need stability (ability to resist unwanted motion).

The pattern (simplified):

| Joint/Region | Primary Need |

|---|---|

| Ankle | Mobility |

| Knee | Stability |

| Hip | Mobility |

| Lumbar spine | Stability |

| Thoracic spine | Mobility |

| Shoulder | Mobility (with stability) |

| Cervical spine | Stability |

Why this matters:

When a mobility joint stiffens, the body compensates by taking motion from adjacent stability joints. A stiff hip creates excessive lumbar spine motion, causing low back pain, while a stiff thoracic spine shifts rotation to the lumbar spine or neck, causing pain and dysfunction.

The longevity protocol identifies three priority areas: hip flexors, thoracic spine, and ankles. These are the mobility joints that most commonly stiffen with modern sedentary life and aging.

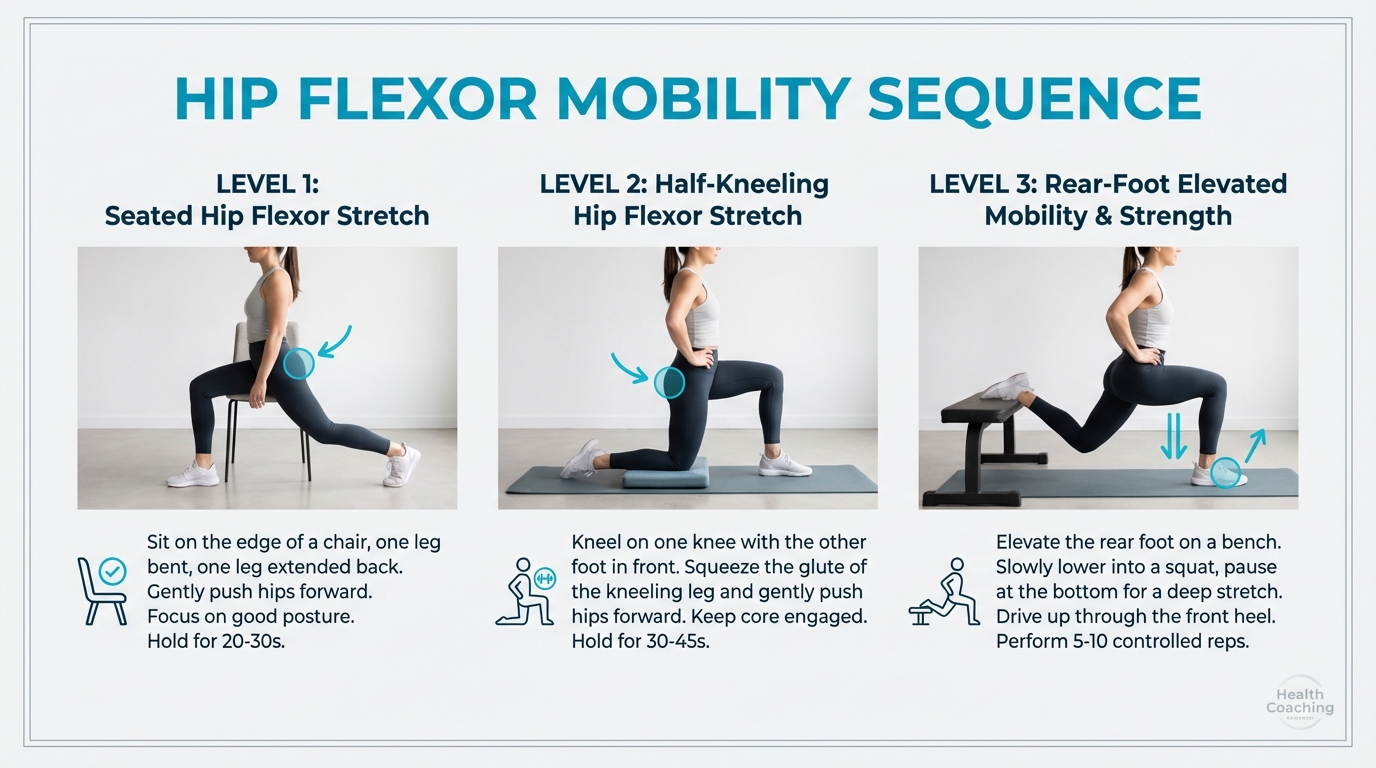

Hip flexor mobility¶

Why it matters:

Tight hip flexors are epidemic in sitting cultures. Your hip flexors—the muscles at the front of your hip that lift your thigh toward your chest—shorten when you sit. The main hip flexor is the iliopsoas (pronounced "ill-ee-oh-SO-as"), a deep muscle that connects your spine to your thigh bone. Over years of sitting, these muscles adaptively tighten, pulling the pelvis forward, compressing the lumbar spine, and limiting hip extension during walking.

Research shows hip extension ROM predicts chair-rise performance and advanced lower extremity function in older adults.[^4]

Simple mobilization progression:

Level 1: Half-kneeling hip flexor stretch

- Kneel on one knee, other foot forward (90° angles at both knees)

- Tuck pelvis slightly (posterior tilt) to feel stretch in front of rear hip

- Hold 30-60 seconds each side

- Key cue: Squeeze glute on rear leg; keep torso upright

Level 2: Posterior pelvic tilt variation

- Same position as Level 1

- Actively tilt pelvis backward (flatten low back)

- This technique has been shown to increase reactive hip flexor torque by 4.85 N·m compared to traditional stretching[^17]

Level 3: Add movement

- From half-kneeling, gently rock forward and back

- Or add a side reach with the arm on the same side as the rear knee

Figure 10.1: Hip flexor mobility sequence - [Visual placeholder: Show the three progression levels with proper form]

Figure: Three progression levels (EXISTING PLACEHOLDER)

Thoracic spine mobility¶

Why it matters:

The thoracic spine (mid-back, T1-T12) should rotate and extend. When it stiffens—from hunching over desks, phones, steering wheels—rotation transfers to the lumbar spine (causing pain) and shoulders (causing impingement).

Simple mobilization progression:

Level 1: Open book

- Lie on side, knees stacked at 90°, arms extended forward

- Rotate top arm open toward ceiling, following with eyes

- Let ribcage rotate; hips stay stacked

- Hold 2-3 breaths, return. Repeat 5-10x per side

Level 2: Quadruped rotation

- On hands and knees

- Place one hand behind head

- Rotate that elbow toward opposite wrist, then toward ceiling

- Lead with eyes and chest. Repeat 8-10x per side

Level 3: Thread the needle

- Start on hands and knees

- "Thread" one arm under the body, rotating torso and reaching through

- Return and reach same arm toward ceiling

- Repeat 5-8x per side

Ankle mobility¶

Why it matters:

Ankle dorsiflexion (ability to bring toes toward shin) is critical for walking, squatting, going down stairs, and maintaining balance. Studies show reduced ankle dorsiflexion ROM and impaired dorsiflexion force control in older adults are linked to poorer balance, gait control, and higher fall risk.[^18][^19]

Simple mobilization progression:

Level 1: Wall ankle stretch

- Face wall, toes 2-4 inches away

- Keeping heel down, drive knee toward wall

- Should feel stretch in back of ankle (Achilles/calf)

- Hold 30 seconds; repeat 2-3x per side

Level 2: Elevated ankle mobility

- Place toes on a small incline (book, wedge)

- Drive knee forward over toes

- This biases the stretch toward the joint capsule

- Hold 30 seconds or perform 10-15 controlled oscillations

Level 3: Weight-bearing ankle circles

- Stand on one leg (hold support if needed)

- Trace circles with the standing knee (ankle follows)

- 8-10 circles each direction, each leg

Building the daily habit¶

Morning vs. evening:

- Morning: Brief mobility flow helps counteract sleep position stiffness and prepares body for the day. Focus: 5-7 minutes, gentle intensity

- Evening: Longer mobility work can aid relaxation and address positions held during the day. Focus: 8-12 minutes, moderate stretching

Sample 10-minute morning routine:

1. Hip flexor stretch (Level 1): 60 seconds each side

2. Open book thoracic rotation: 10 each side

3. Wall ankle stretch: 45 seconds each side

4. Cat-cow spinal flow: 10 cycles

5. Hip circles (standing): 10 each direction, each leg

Total: ~10 minutes

Anchoring to existing routines:

The most sustainable habit is one attached to something you already do:

- After waking, before shower

- While coffee brews

- During a specific TV show

- Before bed as part of wind-down routine

Coaching in Practice: "I Keep Forgetting to Do My Mobility Work"¶

Client: "I know mobility matters, but I keep forgetting. It's been two weeks and I've done it maybe twice."

Coach: "What's something you do every morning without fail?"

Client: "Make coffee, I guess."

Coach: "Perfect. Let's attach 3 minutes of mobility to coffee time. While it brews, you do your hip stretches. Make it a package deal—the coffee doesn't happen without the stretches."

Client: "But 3 minutes doesn't seem like enough."

Coach: "Three minutes is infinitely better than zero minutes. Once three minutes becomes automatic, we'll build from there. Right now, the goal is consistency, not duration."

Client: "I'll try."

Coach: "Here's what helps: every minute of hip and ankle mobility is an investment in being able to move well for decades. Picture yourself at 75, getting up easily from the floor to play with grandkids. That's what we're building, one coffee-time stretch at a time."

[CHONK: Section 4 - Balance Training: Fall Prevention]

Balance training: Fall prevention¶

Why balance declines with age¶

Balance isn't a single system. It's the integration of multiple inputs:

- Vestibular system (inner ear): Senses head position and movement

- Proprioception (joint position sense): Feedback from muscles, tendons, joints about body position

- Visual system: Spatial orientation and movement detection

- Muscular system: Strength to execute postural corrections

- Central processing: Brain integration of all inputs and motor response

With aging, all of these systems decline:

- Vestibular hair cells decrease

- Proprioceptors become less sensitive

- Visual acuity and peripheral vision decline

- Muscle strength and power reduce

- Processing speed slows

The compounding effect is dramatic. A 25-year-old can stand on one leg with eyes closed for 30+ seconds easily. Many 70-year-olds struggle to hold 10 seconds with eyes open.

Fall risk and mortality: The stakes¶

Falls are the leading cause of injury-related death in adults over 65. About one in four adults in this age group falls each year. The consequences cascade:

- Hip fractures carry a one-year mortality rate of 20-30%

- Fear of falling leads to activity restriction, which leads to further deconditioning

- Loss of independence often follows a significant fall

- Healthcare utilization increases dramatically

But falls aren't inevitable. Balance is trainable, and training makes a substantial difference.

The evidence for balance training¶

The research is consistent and strong:[^20][^21][^22]

- Any exercise reduces fall rates by approximately 23%

- Balance-focused and functional programs reduce falls by 24%

- Multicomponent programs (balance + strength) reduce falls by 34%

- Exercise reduced odds of falling by 68% (OR = 0.32) in a recent meta-analysis

Specific improvements:

- Berg Balance Scale improved (effect size g = 0.92)

- Timed Up-and-Go improved (effect size g = -0.62)

- Falls efficacy (confidence) improved substantially (g = 1.01)

In patients with osteoporosis (already at high fracture risk), balance training improved:

- TUG by 1.86 seconds

- One-leg stance by 4.10 seconds

- Falls Efficacy Scale by 4.60 points[^23]

The balance training protocol¶

Frequency: 2x per week (per the longevity protocol)

Duration: 15-20 minutes per session

Principle: Progressive challenge, when an exercise becomes easy, make it harder

Single-leg progressions¶

Single-leg work is the foundation of balance training because most falls occur during single-leg stance phases of walking.

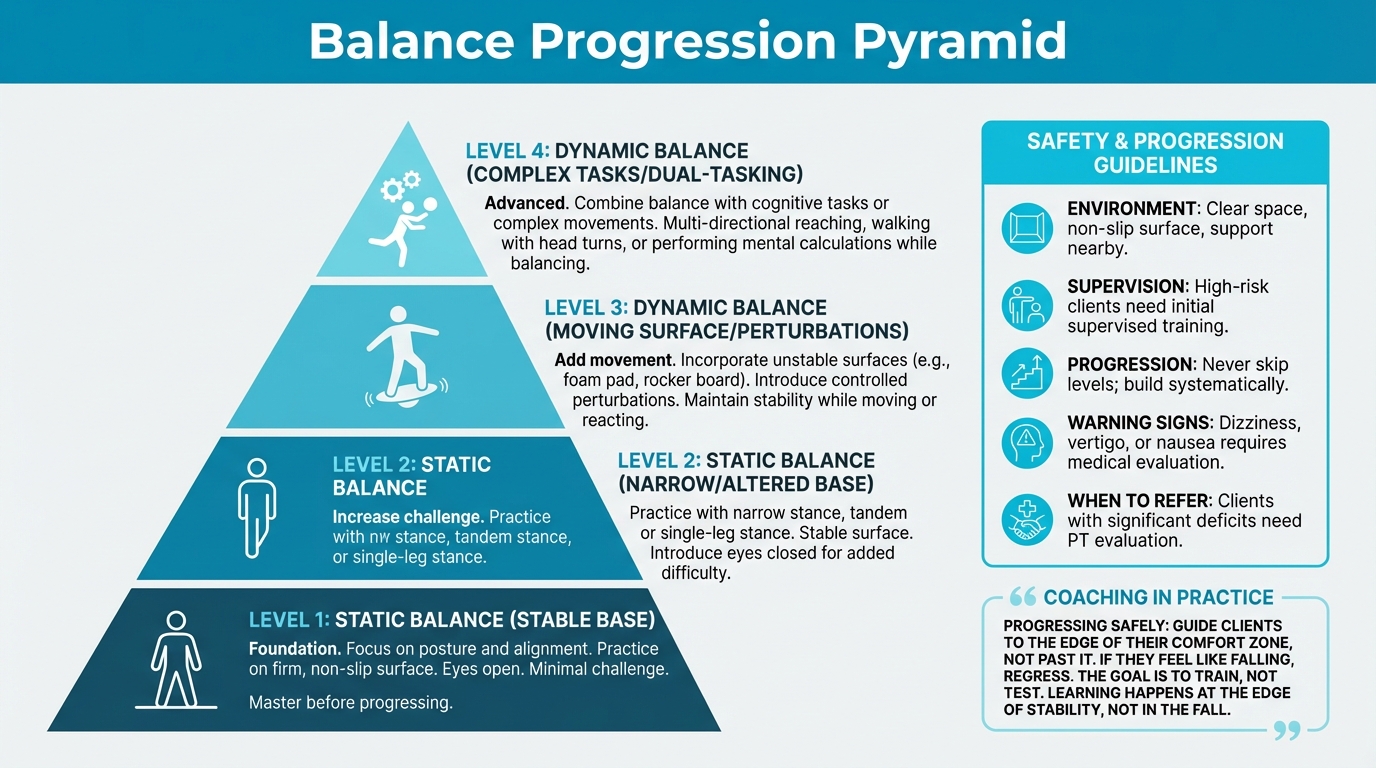

Figure 10.2: Balance Progression Pyramid - [Visual placeholder: Show pyramid with levels from base to top]

Figure: Progression levels (EXISTING PLACEHOLDER)

Level 1: Stable surfaces, eyes open

- Two-leg stance, narrowing base (feet together, tandem stance)

- Single-leg stance with fingertip support on wall/chair

- Progress to single-leg stance, no support, 30 seconds each leg

- Goal: 30+ seconds each leg, stable

Level 2: Eyes closed

- Two-leg stance, eyes closed

- Single-leg stance, eyes closed, fingertip support available

- Progress to single-leg stance, eyes closed, no support

- Goal: 15+ seconds each leg

Level 3: Unstable surfaces

- Single-leg stance on foam pad

- Single-leg stance on balance disc or BOSU

- Progress to eyes closed on unstable surface

- Goal: 20+ seconds on unstable surface

Level 4: Dynamic challenges

- Single-leg stance with arm movements (reaching, catching)

- Single-leg stance with head movements (looking up/down, side to side)

- Walking on beam or narrow surface

- Perturbation training (partner provides gentle pushes to recover from)

For older or less mobile adults:

- Always start near a wall or sturdy support

- Have a spotter present initially

- Progress slowly. It's better to build confidence than to rush and cause a fall

- Consider seated balance exercises initially if standing is challenging

- Chair-assisted single-leg stance (hovering over seat, ready to sit if needed)

Tai Chi and mind-body practices¶

Tai Chi has been specifically studied for fall prevention, with impressive results:[^24]

- Fall risk reduction: RR = 0.76 (24% lower risk)

- Improved TUG by 0.69 seconds

- Improved Functional Reach by 2.69 cm

- Effective in both healthy and high-risk seniors

Why Tai Chi works:

- Slow, controlled movements train balance systems

- Weight shifting challenges stability

- Mind-body focus improves proprioceptive awareness

- Social component improves adherence

- Low-impact reduces injury risk

Yang-style Tai Chi appears more effective than Sun-style, and longer/more frequent practice yields stronger effects.

Other mind-body options:

- Yoga (with balance-specific poses)

- Dance (requires continuous balance adjustments)

- Martial arts (controlled movement patterns)

Safety considerations¶

Balance training has inherent risk. You're challenging stability, which means occasional loss of balance. Safety protocols:

- Environment: Clear space, non-slip surface, support structures nearby

- Supervision: High-risk clients (previous falls, very poor balance) need supervised training initially

- Progression: Never skip levels; build systematically

- Warning signs: Dizziness, vertigo, or nausea during balance work warrants medical evaluation

- When to refer: Clients with significant balance deficits need physical therapy evaluation before unsupervised balance training

Coaching in Practice: Progressing Balance Work Safely¶

Client: "I tried the single-leg stance with eyes closed and almost fell."

Coach: "Then that's too hard right now. I want you working at the edge of your comfort zone, but not past it. If you feel like you're going to fall, back up to the previous level."

Client: "But I want to challenge myself."

Coach: "Think of it like strength training. You don't start with the heaviest weight—you build up. Same with balance. We earn each progression by mastering the previous one. Can you hold single-leg stance with eyes open for 30 seconds without wobbling?"

Client: "I think so."

Coach: "Start there. Get that rock solid before you close your eyes. The goal isn't to test your balance—it's to train it. Each wobbly moment, each recovery, is your nervous system learning. The learning happens at the edge of stability, not in the fall."

[CHONK: Section 5 - Coaching Movement Quality]

Coaching movement quality¶

Assessment-first approach¶

Effective coaching begins with understanding where the client is, not where you assume they are. Before discussing mobility routines or balance progressions:

- Conduct baseline assessments (SRT, single-leg balance, TUG)

- Identify priority areas (what's most limiting function?)

- Match intervention to need (don't prescribe thoracic mobility if hips are the bottleneck)

- Establish measurable targets (improve SRT by 2 points, hold single-leg for 30 seconds)

This prevents the common error of applying generic programs to individual needs. A client with excellent hip mobility but poor balance needs different emphasis than one with the reverse pattern.

Building sustainable routines¶

The best program is one the client actually does. Consider:

Environment design:

- Where will they do mobility work? Is the space ready?

- What equipment do they need (yoga mat, foam pad)?

- Can balance work happen during daily activities (single-leg stance while brushing teeth)?

Time realism:

- What's the minimum they'll consistently do?

- When in their day does it fit?

- How does it integrate with other exercise?

Accountability structures:

- Will they track practice?

- Do they have an accountability partner?

- When will you check in on progress?

Home vs. gym practice¶

Mobility work: Almost entirely home-based, requires no equipment beyond a mat, and is best done daily in short sessions.

Balance training: Can be home-based with appropriate safety measures (clear space, support nearby). Gym/studio setting may be better for clients with significant deficits or when supervision is warranted.

The hybrid model:

- Daily home mobility: 10-15 minutes

- Twice-weekly dedicated balance sessions: Can be part of gym visits or standalone home sessions

- Integration with strength training (Chapter 2.9): Single-leg exercises in strength work double as balance training

Integration with strength training¶

Movement quality work and strength training aren't separate domains. They complement each other:

Strength exercises that build balance:

- Single-leg deadlifts

- Lunges and step-ups

- Single-arm farmer carries

- Turkish get-ups

Mobility work that supports strength:

- Hip mobility enables deeper squats

- Ankle mobility allows proper squat mechanics

- Thoracic mobility supports overhead pressing

Sample weekly integration:

| Day | Primary Focus | Secondary Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Monday | Strength (lower body) | Balance work between sets |

| Tuesday | Zone 2 cardio | . |

| Wednesday | Strength (upper body) | Mobility work as warm-up |

| Thursday | Zone 2 cardio | . |

| Friday | Strength (full body) | Balance progressions as finisher |

| Saturday | Active hobby or VO2 max | . |

| Sunday | Long mobility session | Balance practice |

Progress markers¶

How do you know it's working?

Assessment-based markers:

- SRT score improvement (reassess monthly)

- Single-leg stance time increase

- TUG time reduction

- Grip strength maintenance or improvement

Functional markers:

- Client reports easier daily activities

- Better confidence in movement

- Reduced stiffness in morning or after sitting

- Improved performance in recreational activities

Qualitative markers:

- Movement looks smoother

- Less compensation patterns

- Better posture awareness

Scope reminder¶

As a coach, your role in movement quality includes:

- Educating clients about the importance of mobility and balance

- Teaching basic assessments and helping interpret results

- Supporting habit formation around daily practice

- Demonstrating and cuing basic mobility and balance exercises

- Monitoring progress and adjusting difficulty appropriately

- Connecting exercise to clients' values and goals

Outside your scope:

- Diagnosing movement disorders or pathology

- Treating injuries or pain conditions

- Designing rehabilitation programs for clients with significant deficits

- Medical clearance decisions

When in doubt, refer. A client with persistent pain, significant functional limitation, or safety concerns needs evaluation by a physical therapist or physician before unsupervised movement practice.

[CHONK: Section 6 - Deep Health Integration]

Deep Health integration¶

Movement quality connects to every dimension of Deep Health. As you work with clients on functional capacity, consider how these practices ripple outward.

Physical health¶

The obvious connection: mobility and balance directly affect physical function:

- Joint health: Regular movement through full ranges prevents stiffening and cartilage degradation

- Injury prevention: Better balance = fewer falls; better mobility = less compensation and strain

- Movement efficiency: Quality movement reduces energy cost of daily activities

- Pain reduction: Many chronic pain conditions improve with mobility work (though this requires appropriate professional guidance)

Existential/purposeful health¶

This may be the most powerful connection. Movement quality is about independence and autonomy:

- Getting on the floor with grandchildren. Requires hip mobility and the ability to rise

- Traveling without fear. Requires balance and confidence in unfamiliar environments

- Maintaining hobbies. Golf, gardening, hiking all require functional movement

- Not being a burden. Perhaps the deepest fear of aging adults

When clients connect daily mobility practice to these deeper values, motivation transforms. It's not about exercises; it's about the life they want to live.

Mental/cognitive health¶

Movement quality training involves:

- Motor learning: New movement patterns challenge the brain

- Dual-task integration: Balance work while thinking builds cognitive reserve

- Body awareness: Proprioceptive focus improves mind-body connection

- Confidence: Knowing you can catch yourself reduces anxiety about movement

Research shows that functional movement capacity (measured by tests like the FMS) correlates with cognitive function and may predict cognitive decline.[^25]

Emotional health¶

Movement quality builds:

- Self-efficacy: "I can do this" translates to other life domains

- Reduced fear: Fear of falling is debilitating; balance training directly addresses it

- Empowerment: Taking action on aging concerns reduces helplessness

- Body positivity: Appreciating what the body can do, not just how it looks

Social/relational health¶

Group-based options enhance social connection:

- Tai Chi classes: Community + balance training

- Yoga studios: Social environment + mobility work

- Walking groups: Can incorporate balance challenges

- Partner exercises: Balance work with a friend or spouse

For isolated clients, suggesting group-based movement quality work addresses two needs simultaneously.

Environmental health¶

Consider the physical environment:

- Home safety: Are there tripping hazards? Adequate lighting? Grab bars where needed?

- Outdoor access: Safe places for walking and balance practice?

- Equipment access: Basic tools for mobility work (mat, foam roller)?

- Seasonal factors: How does winter ice or summer heat affect movement options?

Environmental barriers often explain why clients don't practice. A client without safe walking routes faces different challenges than one with a home gym and level sidewalks.

Coaching in Practice: Connecting Movement Quality to Deeper Meaning¶

Client: "I did my mobility work this week, but it feels kind of pointless. I'm not getting faster or stronger."

Coach: "When you work on your balance, you're not just preventing falls—you're preserving your independence. Every session is a vote for remaining autonomous as you age."

Client: "I guess. It just doesn't feel like I'm accomplishing anything."

Coach: "This hip mobility work isn't about being flexible. It's about being able to get on the floor with your grandkids. It's about traveling without stiffness. It's about living fully for decades to come."

Client: "I hadn't thought about it that way."

Coach: "The goal isn't to score well on a test. The goal is to live the life you want at 70, 80, 90. These practices are how you build that future. Does that change how it feels?"

[CHONK: Key Takeaways and Summary]

[CHONK: Key Takeaways and Summary]

Key takeaways¶

-

Movement quality predicts longevity independently of exercise quantity: The sitting-rising test, balance ability, and functional capacity all predict mortality, often as strongly as cardiorespiratory fitness.

-

Nearly half of older adults can't rise from the floor unassisted: This isn't inevitable; it's trainable. Functional capacity responds to practice at any age.

-

Simple tests provide powerful information: The SRT, single-leg stance, TUG, and grip strength require no expensive equipment but offer validated insights into mortality risk and functional status.

-

Daily mobility prevents what's harder to remediate: 10-15 minutes of daily mobility work, especially for hips, thoracic spine, and ankles, maintains what you have. Recovery of lost range requires much more effort.

-

Balance training significantly reduces falls: 2x/week balance practice reduces fall risk by 23-34%. Single-leg progressions, Tai Chi, and structured balance work all help.

-

Movement quality connects to independence and meaning: The "80-year-old you" question makes movement quality concrete: can you get up from the floor to play with grandchildren? Travel confidently? Maintain hobbies?

-

Assessment guides intervention: Test before training so you can identify limitations and match protocols to needs, and track progress with measurable markers.

-

Your role is support and education: Teach assessments, explain the evidence, build habits, demonstrate progressions, and refer when clients need physical therapy or medical evaluation.

Study Guide Questions¶

These questions help you think through the material and prepare for the chapter exam. Try answering a few as part of your active learning process.

-

What does the sitting-rising test measure, and why is it such a strong predictor of mortality?

-

What are the three priority areas for daily mobility work according to the longevity protocol, and why each?

-

Describe the four levels of the single-leg balance progression and when to advance.

-

How does balance training reduce fall risk? What effect sizes does the research show?

-

What distinguishes mobility "maintenance" from "remediation"? Why does this matter for daily practice?

-

When should you refer a client to a physical therapist rather than continuing with movement quality coaching?

Self-reflection questions:

-

Try the sitting-rising test right now. What's your score? What does this tell you about your own movement quality and balance?

-

How long can you balance on one leg with your eyes closed? What would improving your balance by 30 seconds mean for your long-term fall risk?

References¶

-

Araújo CGS, de Souza e Silva CG, Myers J, Laukkanen JA, Ramos PS, Ricardo DR. Sitting–rising test scores predict natural and cardiovascular causes of deaths in middle-aged and older men and women. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2025. doi:10.1093/eurjpc/zwaf325

-

Stutzenberger L, Whited T. Floor-to-Stand Transfers in Older Adults: Insights into Strategies and Lower Extremity Demands. Geriatrics. 2025;10(5):119. doi:10.3390/geriatrics10050119

-

de Brito LBB, Ricardo DR, de Araújo DSMS, Ramos PS, Myers J, de Araújo CGS. Ability to sit and rise from the floor as a predictor of all-cause mortality. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2012;21(7):892-898. doi:10.1177/2047487312471759

-

Coyle PC, Knox PJ, Pohlig RT, Pugliese JM, Sions JM, Hicks GE. Hip Range of Motion and Strength Predict 12‐Month Physical Function Outcomes in Older Adults With Chronic Low Back Pain: The Delaware Spine Studies. ACR Open Rheumatology. 2021;3(12):850-859. doi:10.1002/acr2.11342

-

Brown C, Oktapodas Feiler M, Anson ER, Simonsick EM. Narrow Walk, Condition II, Semi-Tandem, Tandem, and Single Leg Stance Test Failure Could Predict Falls in Older Adults. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing. 2025;62. doi:10.1177/00469580251337269

-

Treacy D, Hassett L, Schurr K, Fairhall NJ, Cameron ID, Sherrington C. Mobility training for increasing mobility and functioning in older people with frailty. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022;2022(6). doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010494.pub2

-

Gao Y, Du L, Cai J, Hu T. Effects of functional limitations and activities of daily living on the mortality of the older people: A cohort study in China. Frontiers in Public Health. 2023;10. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.1098794

-

Ge Z, Li C, Li Y, Wang N, Hong Z. Lifestyle and ADL Are Prioritized Factors Influencing All-Cause Mortality Risk Among Oldest Old: A Population-Based Cohort Study. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing. 2024;61. doi:10.1177/00469580241235755

-

J Geriatr Phys Ther. Reliability and Validity of the Floor Transfer Test as a Measure of Readiness for Independent Living Among Older Adults. 2017. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29059121/

-

Kunutsor SK, Isiozor NM, Voutilainen A, Laukkanen JA. Handgrip strength and risk of cognitive outcomes: new prospective study and meta-analysis of 16 observational cohort studies. GeroScience. 2022;44(4):2007-2024. doi:10.1007/s11357-022-00514-6

-

Milman R, Zikrin E, Shacham D, Freud T, Press Y. Handgrip Strength as a Predictor of Successful Rehabilitation After Hip Fracture in Patients 65 Years of Age and Above. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2022;Volume 17:1307-1317. doi:10.2147/cia.s374366

-

You Y, Wu X, Zhang Z, Xie F, Lin Y, Lv D, et al. Association of handgrip strength with health care utilisation among older adults: A longitudinal study in China. Journal of Global Health. 2024;14. doi:10.7189/jogh.14.04160

-

Van Grootven B, van Achterberg T. Prediction models for functional status in community dwelling older adults: a systematic review. BMC Geriatrics. 2022;22(1). doi:10.1186/s12877-022-03156-7

-

Brown C, Oktapodas Feiler M, Anson ER, Simonsick EM. Narrow Walk, Condition II, Semi-Tandem, Tandem, and Single Leg Stance Test Failure Could Predict Falls in Older Adults. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing. 2025;62. doi:10.1177/00469580251337269

-

Xie K, Han X, Hu X. Balance ability and all-cause death in middle-aged and older adults: A prospective cohort study. Frontiers in Public Health. 2023;10. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.1039522

-

Afonso J, Andrade R, Rocha-Rodrigues S, Nakamura FY, Sarmento H, Freitas SR, et al. What We Do Not Know About Stretching in Healthy Athletes: A Scoping Review with Evidence Gap Map from 300 Trials. Sports Medicine. 2024;54(6):1517-1551. doi:10.1007/s40279-024-02002-7

-

González-de-la-Flor Á, Cotteret C, García-Pérez-de-Sevilla G, Domínguez-Balmaseda D, del-Blanco-Muñiz JÁ. Comparison of two different stretching strategies to improve hip extension mobility in healthy and active adults: a crossover clinical trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2024;25(1). doi:10.1186/s12891-024-07988-9

-

Ko D, Lee H, Lee H, Kang N. Bilateral ankle dorsiflexion force control impairments in older adults. PLOS ONE. 2025;20(3):e0319578. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0319578

-

Hernández-Guillén D, Tolsada-Velasco C, Roig-Casasús S, Costa-Moreno E, Borja-de-Fuentes I, Blasco J. Association ankle function and balance in community-dwelling older adults. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(3):e0247885. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0247885

-

Yu H, Zhong J, Li M, Chen S. Effects of exercise intervention on falls and balance function in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ. 2025;13:e20190. doi:10.7717/peerj.20190

-

Gillespie SH, et al.. Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community: an abridged Cochrane review. Br J Sports Med; 2019. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31792067/

-

Papalia GF, Papalia R, Diaz Balzani LA, Torre G, Zampogna B, Vasta S, et al. The Effects of Physical Exercise on Balance and Prevention of Falls in Older People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020;9(8):2595. doi:10.3390/jcm9082595

-

Hao J, et al.. Effects of Balance Training on Balance and Fall Efficacy in Patients with Osteoporosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Rehabil Med; 2023. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10348058/

-

Chen W, Li M, Li H, Lin Y, Feng Z. Tai Chi for fall prevention and balance improvement in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Frontiers in Public Health. 2023;11. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1236050

-

Farrell SW, Pavlovic A, Barlow CE, Leonard D, DeFina JR, Willis BL, et al. Functional Movement Screening Performance and Association With Key Health Markers in Older Adults. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2019;35(11):3021-3027. doi:10.1519/jsc.0000000000003273